BWV 924–8, 930 – “Little” Preludes from the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Plus: Olga Pashchenko's guessing game, KiiiKiii's attention economy, Adrienne Chung's sonnets, and more!

I spend a lot of time in this slot writing about Canadian artists. I did it last month and in December; February featured Timothy Archambault, whose family comes from Canada. And I’m about to do it again: I’m about to plug Manitoba-born Cree singer Sebastian Gaskin’s excellent debut album LOVECHILD. But before doing so, it might be worth pausing to consider what gives—why all the Canada?

There are some basic structural reasons. Canada may have something like an eighth of the population of the U.S., but its indigenous population is closer to half the size. I don’t want to mislead with overly precise numbers—deciding who “counts” is beyond vexed for all the usual reasons. But there’s no doubt that a much larger portion of Canada’s population is indigenous. And there’s also no doubt that Canada, as a state and as a society, has devoted a great deal more resources to supporting and promoting indigenous cultural forms. There is no U.S. equivalent of the Indigenous Languages Act, no U.S. framework for reconciliation. The Juno Awards have a category for indigenous music. Can you imagine an equivalent at the Grammys?

This support has yielded real results. In recent years, it’s become downright commonplace for indigenous artists (Tanya Tagaq, Jeremy Dutcher) to win the Polaris Music Prize. Indigenous artists in Canada can be popular and even mainstream in a way that U.S. institutions and audiences never quite seem to allow for.

At least, that’s the hope. But there’s a double risk to multicultural politics of this kind. One is assimilation: if you’re aiming for a truly mass audience, you may end up giving them a product that’s not extraordinarily different from the (White) “cultural center.” The other would be tokenization, or indeed historicization of a kind: indigenous artists, to receive their funding, must “represent their culture”—with a sometimes quite static vision of what that culture is to begin with. Taking the money from the state and garnering visibility in White Canada can also mean giving up some degree of artistic freedom. The price of reconciliation is tribal sovereignty.

Sebastian Gaskin’s label, Ishkōdé Records, seems to be very good at navigating Canada’s multicultural politics, garnering multiple Juno wins and coming close to a Polaris win in recent years. They’re also very good at talent acquisition and production: I’ve plugged two of their artists here before, one of whom (Aysanabee) is easily my favorite of the Indigenous musicians I’ve featured. Ishkōdé just puts out good music.

LOVECHILD is no exception. I especially like the more driven and rock-influenced tracks near the beginning (“Safe,” “Shadows”), along with “Ghost,” a real stomper. The collage in “ADHD Interlude” manages both to be refreshingly experimental and not to lose continuity with the rest of the album. And Gaskin can really sing: “Song for Granny” is a great performance.

Does LOVECHILD avoid the two traps I laid out above? I’m not sure. Certainly, it sounds pretty “mainstream,” coming strangely close to Post Malone, albeit without making you want to take a shower after listening to it. (Gaskin himself cites Post Malone as a comp.) Not that there aren’t Native lyrical themes and musical touches: the Cree round dance in the chorus of “Medicine” is very nice and perfectly integrated with the song as a whole. But on the other hand, it sort of feels like, well, (self?) tokenization: here’s a Cree singer, so there’s going to be some round dance music. (Gaskin’s labelmate Aysanabee did it too.)

It may make me a little suspicious, but ultimately the music itself does count for something, and LOVECHILD really is a keeper. (I certainly like it more than actual Post Malone, if that comparison was worrying you.) Give it a listen, and keep an ear out for Ishkōdé’s next releases. Canadian multiculturalism, for all its warts, has given us some very fine music, and I’m sure Canada will continue to be overrepresented in future posts.

BWV 924–8, 930 – “Little” Preludes from the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

BWV 924 in C Major

BWV 926 in D minor

BWV 927 in F Major

BWV 930 in G minor

BWV 928 in F Major

BWV 925 in D Major

There were never “six little preludes.” Well, at least not these six. There’s another group of six (BWV 933– 8) that will get its own post, and those preludes really did constitute a set that was transmitted together. But these six? Not a set at all. They’ve been published as part of “twelve little preludes” and “nine little preludes.” Marvellously, one of the twelve/nine (BWV 929) isn’t even a prelude, one of the nine isn’t a complete piece (BWV 932), and yet another of the nine is almost certainly not by J.S. Bach (BWV 931). Oh, and let’s not get started on the ordering. I had to double-check the BWV numbers too.

The confusion comes from how Bach’s Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was dismembered for later publications. From a certain perspective, it makes no sense to publish the whole book if you’ve already got other Bach works in your catalogue: about half of the book consists of the pieces that would later be collected as Inventions and Sinfonias, while a solid 11 further entries are early versions of Well-Tempered Clavier preludes. Better to just extract the easiest preludes, the music for true beginners, and turn it into a pedagogical publication. And while you’re at it, you can reorder the pieces to fit the same conventions as WTC or the Inventions: note that if you put these pieces in BWV order, the keys go C D d F F g. Smooth.

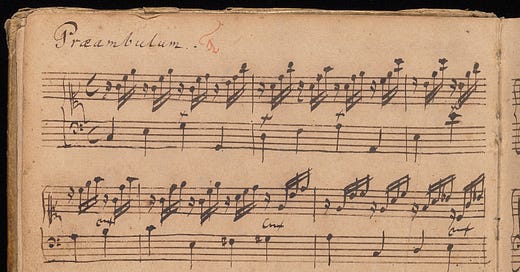

Oh and needless to say, Bach didn’t call them “Prelude” either. Actually, he didn’t call them anything consistent:

That’s one numbered “Præambulum,” one numbered “Præludium,” and two more unnumbered examples of each, one of which comes way later in the book and randomly indicates its key.

All of which is to say that I’m making a compromise here. These pieces don’t really “belong together”: they’re just a series of short prelude-type pieces that were scattered throughout the Klavierbüchlein. Still, they do form an identifiable type of piece that can be extracted from that book, at least once you factor out the future WTC Preludes and the Inventions. These preludes are what’s left over.

But they’re hardly leftovers. I love these pieces, and I’ve already given them a fair bit of attention in the context of my post about “Kidz Bach.” I won’t repost it all here (Substack informs me that some of you click on my links), but I do want to repeat on one particular point I made there:

But all of this assumes that there’s an obvious line between “kids’ music” and “adult music.” That may have become true in the 19th century, but it assumes an idea of “childhood” that was only just coming into shape in Bach’s lifetime. Philippe Ariès may have badly overstated the case, but it does seem like children were seen more like “little adults” in the earlier 18th century than they are now, and certainly the idea of “kids’ music” (especially music that has to “sound like childhood”) just doesn’t seem to have really been a thing.

This is especially evident in Bach’s other collections. The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, famously bills itself as “for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning and especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study composed” (italics mine). Bach titled his published collections “keyboard practice” (Clavierübung) in a way that is again presumably aimed at multiple audiences.

I should have cited the Klavierbüchlein when making this point. In the book itself (browse the original for yourself here!), there is simply no distinction between Well-Tempered preludes (or, for that matter, the preludes that would later be labelled “Invention”) and “little” preludes. It’s nineteenth-century editors who called them “Little.” Bach doesn’t condescend to beginners.

And he certainly doesn’t condescend to them musically. It’s tempting to want to view the first two of these preludes in particular as “drafts” of their corresponding Well-Tempered Book I numbers. The resemblances can be striking:

and

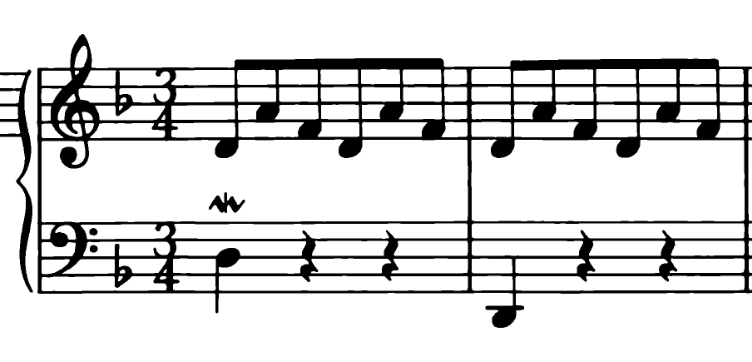

And as pedagogical exercises, these pieces are to some extent developing the same techniques. The “Little” C-major prelude, like the first Well-Tempered prelude, is a piece where there’s only ever one (new) note at a time, distributed between the hands, and the right-hand figuration in the D-minor works over similar technique to its WTC counterpart.

But these pieces are actually in some ways more sophisticated and challenging than those Well-Tempered preludes. The C-major “Little” Prelude is also an exercise in left-hand ornaments, and in fitting them in (long trills!) against steady right-hand figuration:

And the D-minor “Little” Prelude is a delightful study in cross-rhythms, pitting a right hand that often cuts the measure in half against a left hand that steadfastly gives three quarter notes per bar:

And that’s saying nothing about the outburst of sixteenth notes at the end of the piece.

Without going into too much detail (I thought about it and decided to spare you this time), these pieces are also remarkably subtle exercises in carefully varied repetition and judiciously imperfect symmetry. Measures 3–6 of the C-major prelude (0:10–0:28) are a long sequence, repeating basically the same chord progression and contrapuntal framework four times. But Bach subtly switches up both parts; by the time it feels truly repetitive, he’s already moved on.

The other preludes share a common spirit with the Inventions. To me, the D-major Prelude BWV 925 sounds almost like it could be a Three-Part Invention, although of course there are more than three actual parts. I should also tell you that some scholars also think that this piece isn’t by J.S. Bach either, since it only survives in W.F. Bach’s handwriting. Take a listen to W.F.’s harpsichord music and decide for yourself. (Not that we should expect the adult composer to sound like a childish imitation of his father—but on the other hand, you should listen to those Polonaises.)

Then there’s the two F-major preludes, which share the sunny, Italian spirit of the F-major Invention. BWV 927 is so carefree that it doesn’t even use a single accidental (sharp or flat). But don’t be fooled by that glossy surface: it hides remarkable subtleties, albeit ones that take some time to manifest. At first, everything is symmetrical: one phrase answered by another, with that pair in turn mirrored by another and so on up the scale. Measures 3 and 4, for example, are essentially the same as 1 and 2 with the hands reversed. Then we get four square measures of cellos marching up and down a scale while the violins fiddle above. Or—almost four measures:

You’ll notice that the left hand breaks the pattern halfway through measure eight, and again halfway through measure 10. We’re off by half a bar. Vivaldi would be proud.

Bach has to end somewhere, and he doesn’t usually round things off midmeasure. He needs a way out. So he gives us an even quicker series of these “half a beat early” interruptions:

The red lines are meant to help you see a repeating pattern that crosses the boundaries of beats and even measures. It can’t help it: it’s six sixteenth notes—a beat and a half—long. Simply repeating it like this makes the rhythm so topsy-turvy that Bach ends up just short-circuiting the sequence (all those ties!) and calling it a day. Even with a little gesture to round things off, the prelude ends on measure 15, and midmeasure to boot. So much for pairwise symmetry.

OK, so I guess I didn’t spare you the details there. I’ll lighten up a bit on BWV 928, the most developed of these Little Preludes, and indeed probably as close as Bach gets to writing a Handel sonata-style keyboard movement. Like most of Bach’s keyboard pieces in F, it’s delightful and Italianate.

And that’s our final point of comparison with the Inventions. Just as (I think) the E-minor and F-major Inventions were meant to give a taste of French and Italian keyboard styles, so too do the G-minor and F-major Little Preludes (consecutive pieces in the Klavierbüchlein) seem intended to teach playing in those two national idioms. The G-minor prelude could pass as a minuet if it really needed to, and it’s loaded with both French-style ornaments and style brisée arpeggiations. Even the fingering scheme (which seems to come from Bach) would be at home in Couperin’s L’art de toucher le clavecin:

At two minutes and 42 measures (84 with repeats), this piece is also more substantial than many of the preludes in the Well-Tempered Clavier. “Little” is in the eye of the beholder.

What I’m Listening To

Olga Pashchenko – Guess Who?

Look, I don’t like the title either. I’m simply going to hope that Alpha Classics imposed it upon Pashchenko, taking her wonderful selection of songs for the piano by the Mendelssohn siblings and twisting it into a parlor game with a nice patronizing odor (“Doesn’t she write just as well as him?”) to boot.1 It wouldn’t exactly be the first time that commercial interests went with the tritest framing imaginable: if you want to read about Fanny Hensel, you’re probably going to turn to Larry Todd’s excellent biography, and wait until you see that (OUP-imposed) subtitle.

Besides, I really don’t think that it’s as hard to guess who’s who as the album seems to be implying, at least after you take a bit of time to get to know the composers. I know that’s easy for me to say, having performed almost all of Fanny’s pieces on this recording (and having at least read through Felix’s a couple times). And I know that the differences are somewhat subtle; it’s not like guessing Chopin vs. Schumann or even Robert vs. Clara. It’s almost like Felix and Fanny were swapping notes, like they’d heard the same music (had the same composition teacher) growing up.

The best way I can describe the differences between Felix and Fanny, at least as they manifest in this kind of piece (“Songs Without Words”), is one of sheer intensity. Both composer’s song styles are heavily influenced by Rossini and German Lieder, which means keeping the music relatively straightforward (in terms of rhythm and harmony) until the climactic moments. The two composers even use similar gestures for their climaxes: a surprising key change, a shock dissonant chord, a melodic high point. But Hensel always takes things a couple steps further than Mendelssohn, gives the music an extra twist of the knife. She’s more adventurous and more ambitious: all of the longest tracks on the disk are by Hensel. If only she’d been resourced to write symphonies and full-scale oratorios like her brother.

That’s not to say that Mendelssohn’s pieces are lightweight. I think Songs Without Words have a pretty bad, or rather middling reputation, since every piano student has to learn some bland Venetian Gondola Song at some point. But these pieces have serious range, and Pashchenko has selected all of the best ones, all of the pieces with real fire in them, all of the Mendelssohn songs that can stand up to the best of Schubert and the Schumanns. The song Op.62 No.3 is a funeral march of shocking pathos; I’m convinced that Mahler ripped it off for the first movement of the Fifth Symphony (to worse effect, naturally), and in any case Felix here is himself reworking materials from Beethoven’s Fifth, the Eroica (second movement), and the Appassionata. The opening set by itself should give the lie to the sleepy image most people have of this repertoire. Far from being pablum for “intermediate piano volume 7,” it’s virtuosic and thrilling music, a repertoire that should make it onto recital programs far more often.

Still, Mendelssohn even at his most ardent can’t match up to the searing quality of a Hensel piece like Op.8 No.2. For that matter, I’m not sure that he, even at his most lyrical, can match up to the sheer tunefulness of the rest of that set, the “Lenau” song Op.8 No.3 (Hensel calls her pieces “songs for the piano,” with the implication that there are words) and the drop-dead gorgeous Wanderlied Op.8 No.4. As underrated as Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words are, the neglect of Hensel’s Op.6 and Op.8 is downright criminal. You can win “Guess Who?” by simply guessing that the best pieces are by Hensel.

Performances like this one will certainly help: Pashchenko plays both composers’ music with imagination and gusto. She uses her 1830s Graf fortepiano to excellent effect, although I think that the piano actually helps Mendelssohn’s pieces more than Hensel’s. Roughly, the most important difference between a fortepiano and a modern instrument is the same as the difference between Felix and Fanny: a modern piano has a much wider intensity scale, can play with much more of a roar. That might sound like a crippling restraint, and indeed for some repertoire (Beethoven concertos, Liszt, Hensel) I really do miss that lack of ability to turn the music up to 11. (You thought the Spinal Tap jokes were just for April Fools’?) But for a lot of music (Schubert, Mozart, Haydn, Mendelssohn), that smaller range allows you to max out the instrument’s intensity without playing at a volume that’s completely out of proportion to the scale of the piece. Even though the instrument sounds smaller, Mendelssohn paradoxically sounds a lot bigger on it. Pashchenko shows those possibilities marvellously, for both Felix and Fanny. Even if Hensel doesn’t really need the help.

Lady Gaga – MAYHEM

It’s not like you needed me to tell you that there’s a new Lady Gaga album. (Two more such albums under “Also liked…” below.) But hey, as anybody who reads my stuff could probably guess, I really like Lady Gaga. And I think this album has been oddly misrepresented despite the absolute flood of critical and fan appraisals.

Even if you haven’t recently had to learn the phrase “reheating her nachos,” you’ve probably heard that “Gaga is BACK,” that she’s making music like the stuff that made her famous in 2008. The natural contrarian response to which is: “didn’t we already have Gaga is BACK in 2020 with Chromatica?” Well, no. Maybe. Sort of. It depends on what that phrase means, and nobody seems to agree.

The problem is that Lady Gaga was, from the very beginning, a lot of different things. In very general terms, she’s best-known as a Madonna revivalist, a purveyor of synth-driven dance-pop styles. She’s also of course known for trying on a lot of other guises (but what could be more Madonna?), from the pop-rock of Joanne and the shockingly good Star Is Born Soundtrack to the albums of standards with Tony Bennett. I guess for some people “Gaga is BACK” is just about synths and dance music. Chromatica was close enough.

But really not all that close. Chromatica, with its heavy influence from house music, was a real stylistic evolution for Lady Gaga, a genuine musical risk. It paid off with a hit single, but nobody could have accused her of reheating any kind of appetizer then. MAYHEM is different.

For that matter, MAYHEM is fairly different from the 2010-era Gaga that everybody claims it to be drawing on. Very coarsely, you could call The Fame electropop, Born This Way synthpop, and ARTPOP plain EDM: there are real sonic differences between those albums, and you have to decide which era exactly you think Gaga is returning to. Probably nobody thinks it’s ARTPOP, but if MAYHEM is supposed to sound like The Fame or Born This Way then why does it literally sound so different?

Stop singing along for a moment and actually listen to the production on old Gaga hits like “Poker Face” and “Bad Romance” or “Judas.” With their Eurodance influence, those songs are extremely in-your-face. The sound is sparklingly clear. Gaga’s voice is right in the foreground. The lines are sharply etched. Even the extensive Autotune (on The Fame in particular) works to make the sounds more discrete and clarify boundaries. The beats in particular can be so in-focus that I can find it a little hard to listen to some of those songs with headphones.

MAYHEM doesn’t have this sound at all. There’s a lot more air and space in this album, with atmospheric effects, muffled beats, and reverbed-out vocals everywhere. Gaga, despite protestations about microwaving cheesy snack foods, is keeping with the times. If you put them side-by-side, there’s no chance that you’ll confuse this album with her previous music. (Perhaps the tortilla chips have lost a bit of their crispness in the intervening 15 years.)

There is one major thing that ties MAYHEM directly back to the Born This Way and The Fame eras, one thing that audiences are really latching onto. It’s Gaga’s use of language. There’s been a lot of commentary on “Abracadabra, amor-oo-na-na / Abracadabra, morta-oo-ga-ga / Abracadabra, abra-oo-na-na” and its resemblance to the infamous “Ra, ra, ah-ah-ah / Roma, roma-ma / Gaga, ooh, la, la” from “Bad Romance.” But there’s also MAYHEM’s “I’ll t-t-take you to the Garden of Eden” adopting the same stutter as “P-p-p-poker face” and “Papa-paparazzi” and “Judas, Juda-a-as.” And there’s also some unusual scansion in songs like “Perféct Celebrity,” matching the quirky pronunciations of much of Gaga’s early work. Chromatica and Gaga’s non-dance-pop albums don’t treat their lyrics like this at all. Jazz-inspired releases like Harlequin can include scat singing and wordless bridges/outros, but they won’t torture ordinary English in the same way.

So: Gaga IS back. And I need to revise some chunks of my dissertation to feature her more prominently. Few singers do such fascinating things to their lyrics, and I’m glad to have a whole album of new examples.

Jason Isbell – Foxes in the Snow

I’m a certified fan of “Americana” music. You’ve seen the receipts: an ever-expanding list of great albums that I’ve praised to the skies on this blog. But in all of those posts, I’ve studiously avoided defining what this music is. Or rather, I’ve operated under the assumption that the Americana label is supposed to be purposefully anti-genre, to signal a bricoleur’s grab-bag (sorry for the mixed metaphor) of sounds from America’s past. Blues, old-time, bluegrass, rock, folk—put them all in the blender and call the smoothie Americana.

With Jason Isbell, I wonder if I’ve been missing the point. His version of “Americana” is basically just folk with some country. It’s lovely music, heartfelt singing, and excellent songwriting—more on that in a minute. But it doesn’t have the same spirit of adventure as any of the albums linked above. It occurs to me now that all of the other American artists I’ve talked about on this blog are Black, and have a much more complex relationship with old-timey America than this nice White boy from rural Alabama.

Even if his music is less “experimental” or plain “interesting” than Leyla McCalla’s, Isbell still has a lot to offer. Maybe his most special quality is his way with words, in both writing and delivery. Like Olivia Rodrigo and Kendrick Lamar, Isbell induces me to listen to his lyrics without having to make any kind of effort. That’s an extremely high bar to clear: as you can probably tell from my endorsements of Lady Gaga and K-pop, I tend cheerfully to ignore a song’s words, especially on first listen. It takes a certain vocal honesty and a thought-provoking or entertaining character in the lyrics themselves to grab my attention in that way.

That doesn’t mean I love Isbell’s actual words (certainly not like I love Rodrigo’s or Lamar’s). His earnestness can make me cringe a bit. The boy-scout maxims on “Don’t Be Tough” are not an improvement on “If” (hackneyed as that poem is). The title track made me giggle a bit with opening lines “I love my love / I love her mouth / I love the way she turns the lights off in her house,” although it gets a lot better from there. And it’s a shame to open a song like “Wind Behind the Rain” with a helpless cliché like “I knew you before we met / We don't need all the answers yet.”

But at his best (including the chorus of “Wind Behind the Rain”), Isbell can indeed turn a fine phrase. “Ride to Robert’s,” one of the more straightforward folk-style songs on the album, is an evocative bit of storytelling. So too with “Crimson and Clay,” a melancholy number about rootlessness and wanderlust. Isbell pulls a neat trick when he makes you believe “You could strip me of everything I own / And just leave me with the memories of my Alabama home” at the same time as he excoriates the “Little noose in a locker, brown eyes crying in the hall / Rebel flags on the highway, wooden crosses on the wall.” It’s all very well calibrated.

Almost too well-calibrated. Songs like “Crimson and Clay” can feel a bit like Isbell trying to nod to liberal, metropolitan audiences while still keeping his country cred (“Licked the spoon in the kitchen, we prayed to Martha White”). Here’s a comparison that I’m sure would infuriate both parties: it reminds me of Morgan Wallen pointedly fleeing SNL for “God’s country.” Isbell’s part of Alabama, after all, is right on the border with Wallen’s Tennessee.

Part of the problem is that Wallen’s success, from “Whisky Glasses” on, has helped bring to prominence a whole crop of singer-songwriter types who do some kind of country-inflected rock or pop or folk or something. In the age of Noah Kahan, “Americana” is a thoroughly mainstream proposition, and its more stripped-down ballads are pretty close to some of the songs on Foxes In the Snow. In other words: Isbell may be a bit folkier, but in his more sentimental moments, he can sound shockingly like what’s now in the top 40. There are gestures all over “Gravelweed” and “True Believer” (especially in the guitar part) that vividly remind me of Wallen’s 2024 version of “Spin You Around.”

Is that a bad thing? For all of his crassness and lack of artistic focus, Wallen can put out a great song (more typically a great tune or riff), and resembling his work isn’t an inherently bad thing. But it’s not good for Isbell’s branding. For a singer who’s all about raw emotion, about personal authenticity, that whiff of commercialism is a death sentence. Isbell might want to avoid pop chord progressions for the next couple albums. At least until Wallen and Kahan have moved on.

KiiiKiii – UNCUT GEM

I thought I’d been scooped. I had a lot of thoughts about KiiiKiii’s rollout and then the indefatigable Kathryn Xu came out with an in-depth, long-form Defector article about them. This is the same Kathryn Xu whose TripleS article is one of the best things any journalist has written about K-pop. (Also an excellent sportswriter.) She got to KiiiKiii first. I’d have nothing left to say. I was prepared to move on and talk about Yeji’s “Air” or INFINITE’s “Umbrella” or something instead.

Luckily, Xu and I seem to have had almost orthogonal takeaways from KiiiKiii’s debut: she’s bored and I’m overstimulated. The fact that it’s possible (indeed completely reasonable) to have these two seemingly opposite reactions is interesting in itself, and I’ll come back to it at the end. But let me start by laying out the case on either side.

Xu’s main point is something I’ve harped on numerous times in this space. As I put it the first time:

I don’t think that “Americanization” is the biggest musical danger confronting K-pop. The biggest danger is NewJeans.

I think that NewJeans is second only to Bach in terms of number of namechecks on this blog. It’s not because I love them (much the opposite), but rather because their influence is completely impossible to avoid now. The bland, replaceable, TikTokified Newjeans aesthetic has spawned countless imitators (Xu names ILLIT and Hearts2Hearts and TripleS, by which I think she means the subunits AAA and Krystal Eyes) and prompted numerous existing acts (Le Sserafim, æspa, STAYC) to alter their sound. And that alteration has relentlessly proceeded in the direction of “less interesting” or even “less music.” That’s what Xu means when she calls this the “The Dawn Of K-Pop’s Process Era.” It’s market research-driven optimization at the expense of the human. It’s Sam Hinkie’s approach to the 76ers’ front office, or (to use an analogy Xu is too cliché-averse to adopt) a Moneyball version of K-pop:

Better or worse or just different, K-pop as an industry is unquestionably more optimized in its production. If part of that optimization comes at the cost of anything weird, or Too Much, or what used to make K-pop as an industry unique? Well, those aspects—involved concepts, saccharine cuteness, ostentatious and/or ugly styling, dramatic eye make-up on men—also happened to keep K-pop's barrier of entry much higher for global audiences. Now that that's gone, there's not so much to cringe at. There’s also less there.

…

Or, if K-pop is like baseball, then everyone is now the Tampa Bay Rays.

As a Rays fan: ouch. And spot-on.

KiiiKiii’s visuals are indeed an extremely obvious knockoff of NewJeans’, from their individualized outfits to how Haum’s hair was teased to look like Danielle’s. Their first release (“pre-debut”) was also a boring-ass song that could have been put out by any girl group in the post-NewJeans world:

…even if “I Do Me,” like most recent girl group pop, doesn’t really sound like any actual NewJeans song. The main point of commonality is in the stripped-back, shaved-down musical aesthetic. The tune sucks, but it probably couldn’t be any good: if it were too memorable, it would stick out too much. I hate this stuff just as much as Xu does.

But I actually really liked “Debut Song.” Not, like, as a song, but for its memeworthy ridiculousness, especially coupled with that music video. The aesthetic is something like “bootleg karaoke machine” mixed with Kid Pix animations that haven’t been seen since the heyday of M.I.A.:

(Cleverly, all that on-screen text manages to find a different way to introduce each member.)

The music, of course, is terrible, an autotuned mess of excruciating raps, nursery rhymes, random beats, and other such nonsense. But it’s all taken so far as to be downright hilarious. It’s so insane that it’s almost listenable.

Despite “DEBUT SONG”’s insanity and experimental character, it’s not actually all that unique. Xu points to Lil’ Cherry’s “MUKKBANG!” as a precedent, but I think there are more obvious comps within Korean idol pop itself. If you wanted a bizarre autotuned hip-hop version of nursery rhymes, you could listen to BABYMONSTER:

Or if you wanted your nursery rhymes from a group known for incoherent musical mishmashes, you could listen to early NMIXX:

I am convinced that nobody thought these songs are good, or even that anybody but the most hardcore converted fan would want to listen to them. Rather, like so much else in so-called 5th generation K-pop (on the girl group side), the point is to make at least one element of the production (lyrics, music video, song) as bad as possible to get people talking about it:

This is my fan theory for why BABYMONSTER put out trash like “Sheesh” before pivoting to genuinely good songs like “Forever” and “Drip.” A good song gets you nowhere; there are lots of those out there, and it’s not obvious that most listeners care too much. But if you can only grab people’s attention, then they might notice the group and let one of the members catch their eye.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that 5th-gen girl groups have focused so much on either extreme talent (NMIXX are all great singers and dancers; BABYMONSTER has two very good rappers, one great singer, and one of the best singers in the history of Korean idol pop) or extremely striking looks (NewJeans, KiiiKiii). Not that K-pop ignored either in the past (9MUSES members were recruited purely on the basis of having been models, and don’t tell any group’s fans that their members are untalented), but the industry’s involution has reached a near-breaking point. Hook people with a stupid ploy for attention and then keep them on the line with members who are too impressive to ignore. Note that there’s no need for good songs along the way.

Attention and boredom are two sides of the same coin. When everybody is bombarding you with the same sensory artillery, then nothing can stand out. Faced with a steady stream of “Macaroni Cheese” and “O.O,” you just start to glaze over. And it actually makes perfect sense for “DEBUT SONG” and “I Do Me” to be consecutive releases by the same group, for KiiiKiii to slap you in the ears with one song and lull you to sleep with another. These two branding strategies are perfect complements, like doomscrolling and TikTok gardening videos. One music video is an extremely memorable (if unlistenable) watch that you’ll never return to; the other is as unmemorable as possible and you’ll loop it in the background forever.

Virality is fleeting and trends like this reach oversaturation pretty quickly. “Great tunes” as an attention-getting mechanism (the pop charts are the original attention economy) only ever lasts so long before another strategy begins to dominate: ‘60s pop was followed by the doldrums of the ‘70s and 4th-gen K-pop was followed by this crap. Luckily, I think that our current hellscape of simultaneous musical boredom and overstimulation may be approaching its breaking point. With “DEBUT SONG,” the “obnoxious attention-getting” strategy has reached the stage of full-blown, self-conscious parody, and it’s hard to do the same thing with a straight face after being mocked so accurately. I just hope that some group skewers the bland-ass “I Do Me”s of the world soon too.

And there’s still hope for KiiiKiii. I’m not sure I really like any of the other songs on UNCUT GEM, but there’s more going on with them, and they certainly show some promising future directions. More importantly, no other group that’s tried the “in yer face”-style debut has stuck to it. Like I said above, BABYMONSTER’s more recent singles are actually good (although “Woke Up In Tokyo” is from their most recent album). And NMIXX have now taken their “experimental” spirit in a genuinely exciting new direction:

Now that’s a “change-up” I can get behind. Once you have the world’s attention (or at least enough of a fanbase), you can start to make some real music.

Also liked…

Yves Jarvis – All Cylinders

KIRARA – KIRARA

Fahmi Alqhai and Quiteria Muñoz with Accademia del Piacere – Spain On Fire: Divine and Human Passions in the Spanish Baroque

Ada Oda – Pelle d’Oca (h/t: Hearing Things)

Viviane Arnoux, François Michaud, and Herve Samb – &Fusion (La Marche du Bonheur)

DARKSIDE – Nothing

Bonus extremely hyped releases that you probably don’t need me to tell you about but which I really did like a lot:

Lucy Dacus – Forever is a Feeling

Japanese Breakfast – For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women)

What I’m Reading

Poetry, as a kind of music, is all about structured repetition. This is a very convenient fact for a poet like Adrienne Chung, who’s deeply interested in all manner of repetition: past lives, humdrum routines, dreams that mirror (?) reality, the apparatus of Jungian psychoanalysis. Form and content have never been so happy together.

I guess it’s on-brand for me to like Chung’s debut collection, Organs of Little Importance, for its most formally constrained poems. She opens with a ghazal (where the radif is “muslin”—too on the nose for an Islamicate poetic form?) and closes with a full-blown heroic crown of sonnets. I liked some of the stuff in between too (and groaned at others), but it’s those framing gestures that got me.

A heroic crown is an awfully apt way to broach the theme of “I’ve lived not one life but many more.” Chung uses the automatic repetitions of the form to full advantage, giving us two different angles on a line like “This debt, each dawn another Groundhog Day”: in Sonnet VII, it’s the culmination of a poem about sleepwalking through life, while in Sonnet VIII it kicks off a set of free associations with wildlife (hogs→swine) that eventually lead back to the scene of free association (psychoanalysis) itself. Chung’s notes comment that three of the sonnets use material from Dante’s Commedia, and I need to think more about the exact nature of that connection.2

There are other very impressive and ambitious poems in the collection, especially the meditation on memory and perception in “Blindness Pattern” and the paradoxical conjunction of repetition and obliteration in “Problem” (“1. Upon further examination / A. I have confirmed that / i. My vanity…”). It’s a fairly “academic” collection, referencing both Hume and Heidegger (“Date with Dasein,” one of a couple poems where Chung delights in calling the human brain “fatty”). But my favorite poem in the collection is one where she lets her hair down a bit:

21st Century Pizza

I was seduced through a window one night

by a man in a large black headset, miming a waltz

in an empty gaming parlor. Rain fell

as I huddled under the frame like a stray,

waiting for a world to open

through a door.For five minutes, I could work for free

in a sandwich shop, a pet store,

or a pizzeria, which I chose by accident

as he placed the headset onto me,

tightening the straps and asking

if I was OK.I was OK, but possibly unprepared,

something for which I am prepared due to a life

of frequent relocation, general misfortune,

and poor choices in love…There was a pizza shop on Geary

that gave children little balls of pizza dough

to knead to pass the time,

clumps of dampened floursoft as actual angels

in my hands.From that day on, I craved

its supple pliancy, how it yearned

for the empty spaces

between my fingers.

I dreamed of its meat, its sweetness

in my mouth.Years later, when I came home,

no one remembered such a place, dark and narrow

in my mind’s eye, dusted in the fine flour

of memory’s electric powder.There was no photo, no witness,

no evidence to burn

because nothing is real here

except me.

Gorgeous imagery, tightly-wound (but novel) form, and—biggest blessing of all—a consistent tone. Like a lot of recent poetry, there are moments of bathos in Organs of Little Importance that I could have done without. I wish Chung were more comfortable sustaining diction like “death as if birth and birth as if death” without making us trip over lines like “like a tramp stamp whose butterfly wings / can’t fly me to space, debate fate with Shaq.” And with some of the more confessional poetry near the beginning of the book, I couldn’t always tell if I was cringing at the content or the writing.

So, Organs of Little Importance is a little uneven, but what poetry collection isn’t? The sonnets are worth the price by themselves. And don’t forget the pizza.

A few others:

The Nation – How Atlanta Became a Walkable City

The New Yorker – How an American Radical Reinvented Back-Yard Gardening

Current Affairs – ‘Sustainable Fishing’ is a Lie

Eater – Why Smartfood White Cheddar Popcorn Doesn’t Hit Like It Used To

People’s Policy Project – How Many People Live Paycheck to Paycheck?

Bits About Money – Two Americas, one bank branch, and $50,000 cash

Thanks for reading, and see you again soon!

I am aware that I live in a house made of, if not glass, some other material that might not hold up well to a barrage of stones.

For that matter: is it tongue-in-cheek that the first of these poems references Petrarch at the beginning of the final couplet, at precisely the line that confirms the sonnet to be Shakespearian?

Good poetry attracts bad poetry. Joni Mitchell writes

I had a king in a tenement castle

Lately he's taken to painting the pastel walls brown

...at very long range ...you can trace the 'tramp stamp' lines back to that sort of thing...and Mitchell herself is very uneven... a poet's good work pulling out her weaker stuff..

another

At one point Dylan could write

The guilty undertaker sighs

The lonesome organ grinder cries

The silver saxophones say I should refuse you

The cracked bells and washed-out horns

Blow into my face with scorn

But it’s not that way

I wasn’t born to lose you

I want you, I want you

I want you so bad

Honey, I want you

to that descending bass line figure that permeates Blonde on Blonde ... then it was gone... but the words kept coming

sigh