BWV 870 – Prelude & Fugue in C Major from Well-Tempered Clavier Book II

Plus: Nash Ensemble Debussy, Rose Gray turns it up, another Spotify book, and more!

Timothy Archambault (Kichesipirini Algonquin/Métis) is not Iannis Xenakis, but I can see why you’d think so. I’m not sure I know of any other architect-composers, and Archambault’s architectural profile (training at RISD, working for Rem Koolhaas and Frank Gehry, now a director at Oppenheim) is at least as impressive as Xenakis’s (working for Le Corbusier). And maybe it’s a product of that shared training that both Archambault and Xenakis love somewhat forbidding compositions designed on a systematic basis. Just look at the track listing for 2021’s Chìsake:

And then listen to it. Woah.

Still, to me, Archambault’s music resembles not Xenakis so much as Salvatore Sciarrino. His performances often relentlessly explore the range of extended techniques available on his flute: sounding multiple notes at once, bringing hisses and shrieks out of his flute, and generally sounding like a kind of aural hurricane. It’s easy to see why Archambault was signed by the label of a Sunn O))) member.

On September 2024’s Onimikìg, Archambault commits fully to this aspect of his practice. Previous releases, even Chìsake and the numerically-titled Dialogues were mostly based on traditional “songs” of various kinds. By contrast, Onimikìg is an exploration of brontomancy: these are less songs than divinations performed by using the flute to imitate thunder. More than ever, the result sounds a lot like some of the most avant-garde of New Music—like Xenakis or Sciarrino. But of course Archambault got there in a completely different way. Whether he’s playing old “songs” or performing divinations, Archambault’s playing is rooted in a deep understanding of both oral teachings and early recorded archives. Xenakis’s modernism tries to negate the past. Archambault’s draws directly from it.

That would all be fascinating by itself, but there’s one more added wrinkle. What exactly is that on the album cover? Anselm Kiefer?

As it turns out, this is a birch carving. And it’s related to a form of musical inscription that I’m not entirely sure has been discussed by any scholar. (Please prove me wrong in a comment or email.) There are lots of comparative studies of musical notation, but they are basically entirely limited to European and Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Tibetan, Javanese, Indian, Jewish) traditions, maybe with some reference to oral notations used in West Africa.1 You would get the impression that there are no Native American notation traditions.

And yet here Archambault is, giving us scores of his pieces in a notation system that his grandmother taught him. Makes you wonder what else we’re missing. Archambault talks about this and a whole lot more in a riveting dialogue with Raven Chacon. Read it—and listen to Onimikìg.

BWV 870 – Prelude & Fugue in C Major from Well-Tempered Clavier Book II

(In retrospect, I probably should’ve retuned before hitting record—sorry about that low A.)

It recently dawned on me that maybe (just maybe) I didn’t want to write 48 different Well-Tempered Clavier posts. So I’m skipping the rest of Book I and only sticking to Book II for the remainder of the series.

Just kidding. But I did think of a nice way to drastically cut the number: I’ll pair the Book I and Book II preludes and fugues in each key going forward. And that’s how I’ll structure the discussion of this prelude and fugue too. Sorry for making you jump back and forth; here’s a link to the discussion of the C-major entry in Book I.

In this case, it seems pretty clear that Bach wanted someone to make the comparison. (Even if that someone was just himself or a couple of his students.) Aside from their shared key, the opening pieces of Book I and Book II could not be more different.

The contrasts aren’t particularly subtle. Consider texture. Book I’s first prelude is nothing but a long string of arpeggios, relentlessly repeating the same pattern until the final measures. You may remember (or have just refreshed your memory) that Bach was able to write out a version of it that abbreviates the notation as just a long series of half notes or even whole notes. Simple stuff.

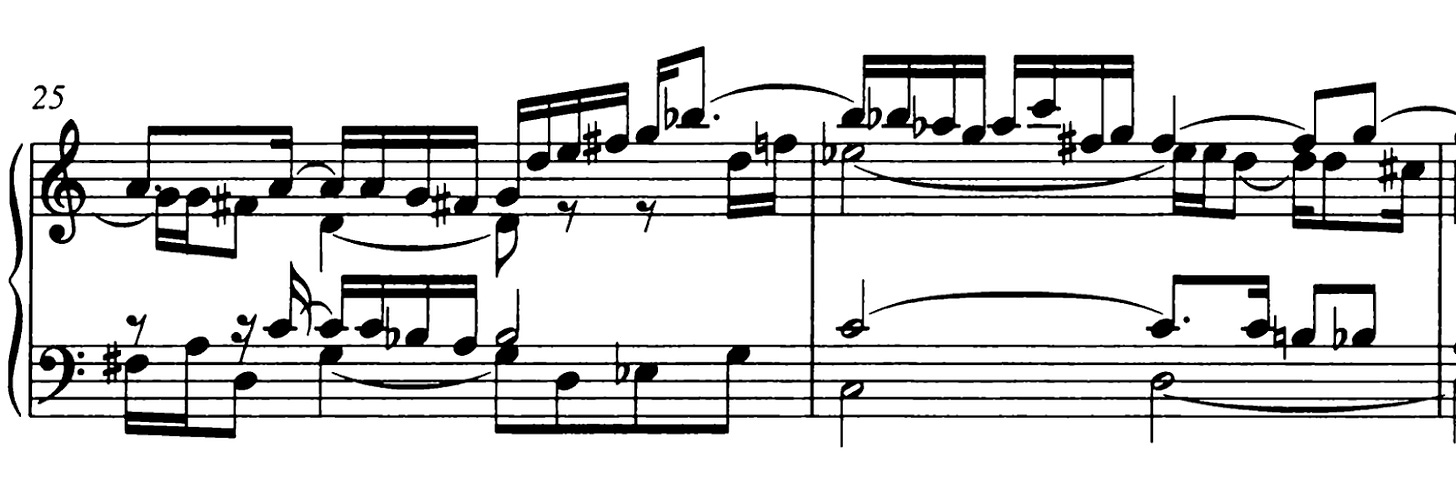

It would be completely impossible to make a similar abbreviation of Book II’s C-major prelude. Where Book I is regular and repetitive, Book II is, well, Baroque:

In the Prelude’s final form, even the rhythm of the first measure is irregular, with those little spurts of thirty-second notes spiking the texture at unpredictable intervals. And even within the long strings of sixteenths, the shapes of the musical figures change constantly. Scale fragments. Rocking back and forth over distances large (sixths) and small (thirds). Triads arpeggiated in just about any order you can imagine.

So Book II starts with a scale where Book I had arpeggios; that’s one way to build a contrast. Another is via harmony. The harmonic “plot” of Book I’s C-major prelude is quite simple, and the music doesn’t stray too far; in my discussion, I focused instead on local rhythms of strong and weak. But Book II wanders all over the place, and in very different directions. Yet again, the very beginning is a contrast: Book I’s first move is to add a sharp and modulate to G Major, while Book II immediately veers flatward and lands on F Major. And on a global scale, where Book I stuck to major keys (with brief gestures toward D minor and A minor), Book II is at least half minor, and often in keys related to the parallel minor, C minor. It’s also full of chromatic thickets, like this measure that manages to use both C-sharp and D-flat (the clavier is, after all, well-tempered):

All of those added complications make it possible for Bach to create a much more overtly dramatic listening experience. The climax of the piece (around 2 minutes into my recording) gets its high tension from precisely those elements that the Book I prelude eschews: it’s built up to via scales, it dwells on a C minor (seventh) chord, and it writhes around melodically at the top of the keyboard.

A final difference from the Book I prelude: because it’s not a uniform series of chords, this prelude can have much more varied counterpoint. That is, Bach can pit a lot of different lines against each other (the previous example, m.19), or he can throw one voice into bright focus by having everything else stop (here, m.26).

Of course, this being Bach, what is written as one voice often implies a whole host of others—and conversely, one line might be distributed between two or more voices. Consider all the different ways in which he writes the same basic “low high lower high” figure:

What variety! Book I could never.

The fugues are just as different. Recall how Book I’s was a stately demonstration of contrapuntal finesse, of how many strettos Bach could build out of a canonical subject. It’s not quite in the old-style “white notation” mode of a choral fugue like the Mass in B Minor’s Kyrie II, but it’s certainly not concertante music.

Book II’s is very concertante indeed, ending with a combination of cardio and gymnastics for the left hand (4:17 in the recording):

Look at those jumps in mm.76 and 78! The second finger has to cross over the thumb, a very fashionable gesture. (For that matter, look at the obstacles the two hands have to hurdle as they tangle with each other at the beginning of the example.)

It doesn’t hurt that the fugue is in 2/4, as up-to-date in 1740 as wolf cuts were in 2020.

Actually, the ending is even more concert-style than it would seem. Here’s one of the more subtle reasons (starting at 4:10):

The last three times Bach has something like the fugue subject enter, it’s in a simplified version in nice, rounded, parallel phrases. (This would later become Beethoven’s preferred way to write a dénouement, in pieces like the Eroica and the first Razumovsky quartet.) It also starts on G all three times, and indeed the same G the first two of those. The whole point of a fugue is that the entrances of the subject are supposed to map out tonal space by starting on different (or at least alternating) pitches each time. By the end of this one, Bach can’t be bothered. He’s having too much fun. Or at least I am.

It’s tempting to make every contrast between Book I and Book II a sign of Bach’s “stylistic evolution.” And as we’ll see in future months, there definitely are trends in Book II that reflect Bach’s interests around 1740, as opposed to the early 1720s when Book I was compiled. But the specific differences between these two prelude-fugue pairs don’t exactly tell us what was new in Bach’s “later style.” The Book II C-major prelude, after all, begins almost identically to a piece that Bach at Bond types might recognize:

This organ prelude, BWV 545a, was written by a Bach in his early 20s. So much for late style.

For its part, the fugue has equally recognizable “early” counterparts. We don’t even have to look far: the Book II C-Major fugue is a cousin of the C-minor fugue from Book I. And the Book I style hung around in other ways too—the famous C-Major prelude is echoed by the C-Sharp-Major prelude in Book II.

Still, I don’t want to deny the differences. There are no 2/4 fugues in Book I, while Book II goes even further and includes fugues in very “fast” and modish time signatures like 6/16. The Book II preludes are in general much more intricate and just plain longer than Book I’s; its C-sharp-major prelude is the only one based on plain arpeggios, as against any number of Book I preludes. The contrasts we’ve seen today will carry through for the remaining Well-Tempered posts. There’s plenty of grist left for the comparison mill. Twenty-three to go.

What I’m Listening To

We are so back. What an incredible month of new music. All I can say is that, much more than usual, I implore you to give not only these four albums but also the “Also liked”s a fair hearing. (Yes: the Benda is actually really good.)

Nash Ensemble – Debussy: String Quartet & Sonatas

The Nash Ensemble has amply earned its reputation as the world’s best performers of “what ensemble has this personnel?” chamber music. For a Hummel Septet, Spohr Octet, or Bax Nonet, they’re all but guaranteed to have the best recording around, and perhaps the only one you can find. More importantly, they’re vital performers of British new music; they’re fabulous with Birtwistle and Turnage.

Because they largely make their bones on repertoire that slips through the cracks, it can be easy to forget that the Nash Ensemble is also just composed of fabulous musicians, capable of turning out world-class recordings of more standard stuff too. This album is a great reminder. These recordings of the Violin Sonata (played by Stephanie Gonley and Alasdair Beatson) and Cello Sonata (Adrian Brendel and Simon Crawford-Phillips) are played with that maddening combination of crispness and dreaminess that fin-de-siècle French music always wants, and the String Quartet is very suave indeed. I’m not sure I’ve heard better recordings of these pieces, including prior releases by the Nash Ensemble themselves.

There’s also a little bit of (very) slightly more offbeat fare. This is a bewitching recording of the other Debussy sonata, the one for Flute, Viola, and Harp (although, as usual, it makes me think that the harp in Debussy’s head was significantly louder and more piano-like than any real instrument). And the opening track is a fun surprise: a one-on-a-part version of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Unlike La mer, which really depends on a plush bed of strings, this piece downright shimmers in slimmed-down form. And it makes me wonder what other repertoire could get the same treatment. Outside of new music, it’s somewhat rare to hear the Nash Ensemble in “chamber orchestra” mode, and now I want more. The musicians certainly sound like they’re relishing the chance.

Sauljaljui – VAIVAIK 尋走

I thought it was a mistake. Not that I knew much of anything about Sauljaljui, but I’d seen that I was supposed to be in for indigenous Taiwanese music. I was. The mistake was that I didn’t know what that could mean.

It’s an interesting quirk of the Taiwanese music industry that a number of its most popular mainstream Mandopop artists are indigenous (coming from under 3% of the Taiwanese population). A-Mei, A-Lin, A-Yue, Tai Ailing, Chang Yu-sheng, and Power Station are some of the biggest names of their generations, and indeed among the most popular singers in Chinese anywhere. But more recently, there’s been a twist. The stars continue to be indigenous, but now they’re making music in their own languages and drawing on their own cultural traditions. (It’s only fair to point out that A-Mei was also including indigenous elements in her music from the very beginning in 1996.) Thus Paiwan pop artist ABAO could win a Best Album Golden Melody Award with an album titled kinakaian 母親的舌頭: “Mother tongue.”

I wonder how all of this has felt for Sauljaljui, who’s been making pop-inflected Paiwan-language music for years. As much as I like kinakaian, the stuff Sauljaljui is putting out is of another order entirely, both in terms of how it integrates elements from traditional music, and simply in terms of quality. VAIVAIK just rocks.

A lot of what drives the record is Sauljaljui’s innovative use of her yueqin 月琴 as part of the rhythm section. Because of the instrument’s timbre and her choice of backing ensemble (the percussion?), the resulting sound can be strangely close to desert blues and other forms of rock from sub-Saharan Africa. Maybe Sauljaljui knows this: opener “Dipin Kari Tang” was apparently inspired by travels in Mauritius and definitely has elements of sega music in it. But there are sounds from all over the world here. “Anun Bala” was written after a trip to Malaysia, and has a whole Pan-Austronesian thing going.

So what you get in this album isn’t indigenous artists making pop; it’s neither A-Mei nor ABAO. And it’s not an album of traditional music or even a simple “traditional plus” fusion project. Rather, Sauljaljui has taken the musical materials available to her and welded them into a unique and very groovy sound. As a “World Music” artist, she’ll probably never get quite the exposure as an ABAO, but she’ll certainly have my ears going forward. She should have yours too.

Rose Gray – Louder, Please

It continues to fascinate me just how separate the U.S. and U.K. pop music scenes have been able to remain. Obviously there’s plenty of crossover, as anybody tired of Adele, Ed Sheeran, Charli XCX, or Dua Lipa (who could be tired of Charli or Dua?) would remind you, but there are some truly bizarre British absences from the American scene. One Direction made it huge in the U.S., but Little Mix? A billion views on Youtube (for one song) and most Americans still haven’t heard of them. It’s bizarre.

The same remains true going quite a bit farther down the scale of stardom. And so we get artists like Self Esteem, who released one of my favorite songs of 2019 and won best album of 2021 from The Guardian, and who I have yet to see even mentioned in a single U.S. music publication. Rose Gray seems to be getting the same treatment.

Like Self Esteem, Rose Gray’s thing is simple: make massive dancefloor stompers. I’m not sure it’s legal for songs to go as hard as “Wet & Wild.” “Angel of Satisfaction” has a goofy Euro-electropop energy that even 2011 K-pop couldn’t match. (The closest I can get is “2010 Lady Gaga does ABBA.”) And most importantly, the album keeps up its gigawatt-scale energy until just about the end. There’s less extraverted stuff like “Switch” (Sabrina Carpenter might have liked a go at that one, except for the dance breaks), and the runway-music spoken word piece “Hackney Wick” is a nice change of pace, but Louder, Please never lets go of the rope. Most accurate album title in years.

P.S.: It’s been a couple months since I complained about PinkPantheress/NewJeans-style music here, so let me just say that “First” (like STAYC’s “SO BAD”) shows how you can take those “Y2K” DnB/jungle sounds and make pop music out of it. Hope someone in Seoul is listening.

Moonchild Sanelly – Full Moon

Speaking of which. Jeju Air 2216 put a bit of a damper in this January’s K-pop calendar—IVE, for instance, postponed their album to February2—so there’s been nothing particularly interesting to speak of. May I offer you another international dancepop release in this trying time?

Although, uh, Moonchild Sanelly might be almost the opposite of K-pop. Korean broadcasters are quite strict about which lyrics and choreographies are allowed on music shows; idols can’t even show their belly buttons on TV. Meanwhile, here are two representative sentences from Moonchild Sanelly’s Wikipedia page:

She gives out sex advice on Valentine’s Day through her social media accounts.[28] In an interview with Basha Uhuru, she called herself “the president of female orgasm.”[29]

Consider yourself warned about the lyrics. I guess that was probably pretty obvious from the title and thumbnail of “Big Booty.”

The lyrics are at least half of the fun though. (You’ll need to look up translations for the Xhosa parts.) I shan’t spoil anything here (think of the children!), but the tagline of “Boom” and the long buildup of “I Love People” are a barrel of laughs in a CupcakKe kind of way. (No links to CupcakKe videos here, sorry.) It’s neither hyperbole nor clickbait for the Observer to have subtitled their review “hustle, energy and smut aplenty”

Still, like Louder, Please, this is also just a fantastic collection of dancefloor bops. It’s a little darker in tone and a lot more abrasive than Rose Gray; since you’re reading this section, think NCT 127 or recent-vintage ATEEZ. But the tracks on Full Moon also fast, both amplifying the harshness of their sonics and really upping the energy level. It’s an absolutely chaotic, absolutely delightful ride. IVE could never.

Also liked…

Clotilde Rullaud – Kananayé

Francesco Corti and Il Pomo d’Oro – The Age of Extremes: W.F. Bach, G. Benda & C.P.E. Bach

Bad Bunny – DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS

Saamba Touré – Baarakelaw

Lambrini Girls – Who Let The Dogs Out

Parchman Prison Prayer – Another Mississippi Sunday Morning

What I’m Reading

I look forward to reading the book, but I think I’d rather get most of my thoughts about the central topics out here.

What was I thinking? What were the odds of that?

Rather than subject you to another 2,000 words of Liz Pelly-inspired ramblings, I thought it might be good to pair Mood Machine with another, much less-heralded recent book about streaming: Glenn McDonald’s You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song. It’s quite a study in contrasts, and McDonald’s book deserves to be better-known. (There’s a review in The Quietus, but I will confess to having discovered it through that bastion of journalistic integrity, Weverse Magazine. Don’t actually read that article: you’ll lose brain cells.)

Now that I’ve been able to read the whole thing: Liz Pelly’s Mood Machine is the most extensive and well-researched critique of Spotify as a corporation and streaming culture in general published to date. It covers everything from the company’s corporate origins (in advertising; music was just a means to an end, decided upon somewhat late in the incubation process), the rise of “lean back” wallpaper music, AI music, algorithmic recommendation, “fake artists,” Spotify as corporate lobbyists, and all of the many new ways in which musicians are now getting screwed out of money. It’s also a great read, as anybody who’s been following Pelly’s work in The Baffler would know.3

McDonald’s book is quite different. It’s almost entirely listener-oriented: where Mood Machine is about Spotify as a corporation, You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song is about, well, you. Specifically, it seems to be designed to tell you about streaming’s origins4 and how it works, to allay your fears, and above all to help you take advantage of the new musical affordances of Spotify and other streaming services. McDonald used to work for Spotify.

If you put it that way, it sounds like one of these books is by a muckraker and the other is by a corporate shill. To a certain extent, that is what they are. Pelly definitely plays her part well, to the extent that her relentlessly negative tone can sound like nitpicking or even fault-finding for the pure sake of it. There are a lot of stray bullets flying around: at the beginning of his company’s three-page appearance Thomas Edison gets dinged as “proto-Musk,” despite (important difference!) having actually worked on his company’s products. For that matter, it tells you a lot about Pelly’s assumed audience (Baffler readers?) that a moniker like “proto-Musk” is automatically assumed to get mouths foaming. A lot of seemingly more neutral words (“efficiency” comes to mind) are thrown around as slights, too. I wonder how Mood Machine reads to people who don’t immerse themselves in left-wing discourse online.

For his part, McDonald definitely can sound like a corporate apologist. But he’s not nearly as committed to that project as Pelly is to hers; perhaps it’s because Spotify laid him off before he wrote the book. So he even affirms claims like “streaming is surveillance capitalism,” and his attempts to smooth over or defuse such fears leave a lot of loose threads hanging. McDonald knows that a lot of Spotify’s business practices are unethical: he never even gives the “pro” case for his true bugbears like Machine Learning (I wonder what he thinks about LLMs?) or, strangely, A/B testing. It’s hard to sustain a true opposition between You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song and Mood Machine when the biggest political proposal advanced by each books is the same: universal basic income.

If McDonald can be accused of anything, it’s a certain naïveté—an attitude that might even be a little studied. He seems to have interacted with a relatively small portion of the team at Spotify, and to have taken people at their word about what they were and weren’t doing; he assumes best intentions all around. He also seems to be doing his best not to think about Corporate’s goals and how much money they make off the back of musicians. Much to his chagrin, I suspect McDonald would learn a decent amount from Pelly’s book.

In the end, I was surprised to find myself in many ways more sympathetic to McDonald than to Pelly. I think part of it is that Pelly gears her book toward the havoc that’s been wreaked on a very particular slice of independent music (and often gives subtle acknowledgments that the harm was done by piracy and iTunes long before Spotify). I like some of that stuff, but I’m much more of a McDonald-style listener. McDonald, as his Every Noise At Once project amply demonstrates, is obsessed with learning about new kinds of music. Indeed, you wouldn’t know it from the jacket, but You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song is in large part the memoirs of a starry-eyed globalist, a paean to cosmopolitanism with music as the way in. It’s a book by somebody who loves music, who doesn’t think it’s at all ridiculous to unironically recommend replacing all other leisure activities (and silence) to cram as much music as possible in. I laughed, but I also felt an uneasy kinship.

At the same time, McDonald’s is not a love that allows for much critical reflection or learning. One of the best reasons to read You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song is as a set of symptoms, an exemplar of an approach to music listening that can treat songs and genres as disposable and interchangeable; you see if you like it or don’t, and then you move on to the next microgenre. In an excursus inspired by dansband music, McDonald proceeds to give a giant list of “goofy” music genres generally only appreciated by people within a particular country. Maybe for somebody listening in a completely naïve fashion schlager and manele can sound like kind of the same thing (I have doubts!), but they are produced by vastly different musicians (White vs. Roma) and for vastly different listening audiences (in terms of factors like age and class).5 It’s not that McDonald doesn’t recommend learning more about music’s role in other cultures—he does quite a lot of that, actually—but he can be strangely incurious about what these songs might mean, to either their target audience or to himself.

If you have to read one of these two books, I guess I have to recommend Pelly’s. The writing is way better (Simon and Schuster, it turns out, has better editors than the one dude who seems to run “Canbury Press”) and there are lots of intensely useful footnotes. But Mood Machine certainly doesn’t obviate or negate You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song. I think McDonald is closer to the truth when it comes to certain business-side things (like the impact of pro rata streaming payouts6), and he also is simply interested in very different topics from Pelly. I’m fairly sure that it’s not “both sides”ing the matter to say that they’re both worth reading.

By way of closing, I guess I should mention the one time McDonald comes up in Pelly’s book. It’s a representative moment for both authors. When discussing Every Noise, Pelly quotes a number of musicians from various small musical scenes (especially hyperpop) who were upset at the impact that naming their microgenre has had. It’s fair to say that McDonald probably shouldn’t have had naming power over so many genres he had no connection to. But the substance of these musicians’ complaints is, well, the typical response of hipsters to their scene being recognized and mainstreamed in any context. And funny enough, there’s an excellent exploration of this response—of the lifecycle of musical genres and scenes—in McDonald’s book (Chapter 18). As usual, McDonald sounds naïve or even a bit amateurish, and his writing is blog-style, not Baffler-style. But, as with so much else in these books, I end up much closer to his side than I would have expected. Read both and see for yourself.

A few others:

New York Times Magazine – How My Trip to Quit Sugar Quickly Became a Journey Into Hell

Followup: The Juggernaut – How Mango Lassi Conquered the World

And: Emma Baccellieri – Which Federal Reserve Banks Have Coke Freestyle Machines?

FanGraphs – Home/Road Splits as Absurdist Comedy

New Statesman – How we misread The Great Gatsby

Sixth Tone – The Big Switch: Unpacking China’s EV Boom

WBEZ – Where Chicago’s ‘L’ meets the railroad: A history is dug up in Lincoln Park

Bachtrack – All in the balance: Bachtrack’s Classical Music Statistics 2024

Thanks for reading, and see you again soon!

For that matter, it’s also pretty rare to see references to non-staff European traditions like Canntaireachd and Znamenny chant.

Prerelease track “Rebel Heart” is quite good but there’s almost nothing to say about it beyond “so I guess they’re recycling this formula again?”

A mea culpa: when I said that Eric Drott’s book didn’t offer a huge amount beyond what industry journalists had already published, I didn’t realize that basically every article floating around the back of my mind was by Pelly. Her book doesn’t quite replace his, but it’s close.

Neither of these books—nor anything in English—does a very good job of explaining streaming’s origins in fine detail, since none of them want to take a global perspective; MelOn predates Spotify by several years.

Thanks to Anna-Marie Sprenger for introducing me to manele; I might have bought this passage hook line and sinker without their guidance.

Although, for the love of God, some streaming service needs to figure out how to make it so that symphony movements don’t earn the same amount as recitatives.

Hmmm...Sciarrino :) .. Birtwistle...Turnage ... stirs up nostalgia for the old Queen Elizabeth Hall...... The Nash People have made excellent recordings of 2nd Viennese as well ...

Maybe the Hurrians exported their notation...