Week 26: 29 April 2024 – Prelude and Fugue “St. Anne” and Easter 5

Plus: Bach's "multilingualism," Yuqi's harmonies, Cindy Juyoung Ok's debut, and more!

A logistical note that I’ll be repeating for the next few weeks: in order to round out the count of recitals at 30, there is going to be one “extra” concert on Wednesday 22 May, same time, same place. There’ll be a reception afterward—see you all there!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

Although I’ve really enjoyed getting to know the music of Anishinaabe collective Nimkii and the Niniis this week, I don’t think I’m exactly in a position to evaluate it. To be clear, I’ll definitely recommend it: their drumming and singing sounds great, and the spoken tracks in their latest album are thoughtful and thought-provoking complements to the music. The best I think I can say is that their music has wonderful energy and variety, played and sung with obvious commitment. As much as I like many of the more “mainstream pop” indigenous artists I’ve been exploring here, it’s equally nice to hear musicians who believe in that traditional music can be equally “contemporary.”

Week 26: 29 April 2024 – Prelude and Fugue “St. Anne” and Easter 5

Please save applause for the end of each set

Prelude in E-flat, BWV 552/i

Wir gläuben all’ an einen Gott, BWV 680

Fughetta super Wir gläuben all’ an einen Gott, BWV 681

Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott, BWV 1098

Wir gläuben all’ an einen Gott, BWV 765

Fugue in E-flat “St. Anne,” BWV 552/ii

Is there anything better than the E-flat-major Prelude? I don’t mean “is there any Bach better” or “any organ piece” or even “any music.” I mean that it beats out walks in the park, Golden Retriever puppies, cherry pie, and anything you can think of. Fresh bed linens? Can’t compare. Sitting by the fireplace on a snowy day? Not in the same league. Even, the person who invented sliced bread probably thought it was the best thing since the E-flat-major Prelude.

Justly, there aren’t many Bach organ pieces more well-known than this one, and since it has a well-defined structure with characteristics that are easy to identify and describe, a lot of facts about it are drilled into organists’ brains early on. I hope you won’t mind me rehearsing all that, and maybe going a little long with the discussion of this one. It’s a huge piece (at 205 long measures and 9 or so minutes, its only rival is the Toccata in F); so it deserves commensurately lengthy discussion.

Before getting to the prelude itself, maybe it’s good to address the elephant in the room: why split this prelude and this fugue? Why cut BWV 552 in half? Having written two long rambles justifying the unity of most Prelude and Fugues—even suggesting that most of them would be better off under the plain title of Prelude—I guess I have some explaining to do.

Really, the existence of these pieces (the E-flat-major Prelude and the “St. Anne Fugue”) is one of the main reasons people ever argue against keeping preludes and fugues together. These are the only prelude (outside of a suite) and the only organ fugue that Bach ever published. And he didn’t publish them together: they’re the bookends of the Clavierübung III collection, with no indication that the pieces “go together” beyond having been published in the same volume. It’s later editors (and BWV cataloguers) who decided to pair the socks and file these two pieces together as a “Prelude and Fugue.” After all, that would make this piece (and the prelude and fugue format as a whole) match Johann Nicolaus Forkel’s description of Bach organ recitals, which he says began with a prelude and ended with a fugue.

Sort of. Actually, what Forkel wrote is that, when Bach was given a theme to improvise on, he would begin with a Prelude and Fugue [“zu einem Vorspiel und einer Fuge”] on that theme, in addition to the fugue that rounds out the concert. So now the socks look a little bit less matching.

Besides, this prelude and this fugue just aren’t like the other, um, stockings in Bach’s wardrobe. Both in their length and their internal structure, each is far, far more complex than any member of a Bach prelude-fugue pair. The E-flat prelude, for instance, includes a fugue (in two different sections), and a double fugue at that.

Now, it wouldn’t be the first Bach Prelude you’ve heard that includes two fugues. That’s the old-style “five-part” North German organ prelude format, and Bach uses it in pieces like the E-major Prelude BWV 566 and the A-minor Prelude BWV 551. So in that sense the E-flat-major prelude is something of a throwback.

In other senses it’s anything but. Let’s introduce our main characters. Here’s what the three main musical components of the piece look like—starting with the opening:

An interlude:

And the fugue theme:

These sections come and go in something like the style of a Vivaldi concerto’s ritornello form; the opening section bookends the piece, returns after the first interlude, and threatens to return between the second interlude and the fugue. (That’s an “ABACABCA” format overall, thanks for asking.) So in that sense the piece nods to super “modern” orchestral forms at the same time that it evokes old-fashioned organ styles.

The stylistic blending doesn’t stop there. Let’s zoom in on the first two sections in particular:

Placed side-by-side, the differences are striking, even just visually. And they should actually be even more apparent—the pedal notes in mm.38 and 40 should be taken in the hands. So we have a thick, five-voice textured above, a thinner, three-voice one below; hands and feet versus manuals alone; dotted rhythms vs straight quarter notes; slurs vs. dots; longer mordents vs short trills. As has often been pointed out, these differences can more or less be summed up as a contrast between French and Italian styles.

In some ways, Bach primes us to hear this “national” contrast: remember that the previous publication in the Clavierübung series contained a French Overture and an Italian Concerto. (With the former transposed to a somewhat awkward new key in order to make the tonal contrast even more audible.)1 Now, it’s important not to get too swept away in this comparison. The opening section of the Prelude, while certainly related to the emphatic and grand dotted rhythms of French overtures, is also markedly different, using only relatively slow and mostly descending strings of sixteenth notes instead of the rapid, sweeping, upward-moving tirades that animate actual French overtures:

It would also be practically unheard-of to play an actual French overture with slurs like what Bach’s marked in the E-flat prelude. (The “Italian” section, for its part, is clearly more of a trio than a concerto.)

Still, the “national” contrast is very real. Consider the harmonic language of these two sections: the “French” part is, true to the music of composers like Rameau, almost entirely composed of seventh chords, with lots of suspended ninths and other rich dissonances. The “Italian” interludes, meanwhile, are limited to triads, with relatively simpler suspensions. The French sections go to the relative minor (E-flat major to C minor); the Italian ones bring in the parallel minor (E-flat major to E-flat minor).

There are also major differences of harmonic rhythm: the Italian muisc is shifted up a gear from the French, so to speak. On one level, its harmonies move a lot faster: the chord changes every quarter note in the interludes as opposed to every half note in the French sections. And yet, in another sense the harmonies also move slower in the Italian sections than in the French: using all of the tricks of repetition that he learned from Vivaldi, Bach makes us accept what is functionally four bars of the same chord at the beginning of these interludes. Change voicing, change octaves, change manuals, rinse and repeat:

This is wholly distinct from the “French” sections, which are constantly on the move, going through sequence after sequence in search of the next cadence.

I haven’t said anything yet about the third theme, the fugue. It’s often tempted scholars and organists to call this the “German” section. Fugues are “German,” after all, and so is pedal writing like this:

But I think it’s safer to call the fugues something like a reconciliation of the other two sections. The upper fugue subject integrates the syncopations of the “Italian” interlude, and the lower subject that underpins it evokes its moving bassline. But the full harmonies, suspensions, constant sequences, and five-voice textures in the pedal fugue equally point to the “French” section. And, rather than sounding like a standard German organ fugue, the constant running sixteenths in this section actually evoke Bach’s Vivaldian style. This section is the closest the Prelude gets to giving us “concerto” style.

Maybe that’s the most remarkable thing about this Prelude. It pits two styles of music against each other, trying to maximize the contrast between them in as many ways as possible. But it also finds a way to fuse them into a third, equally distinctive style. And it’s no dry intellectual exercise: the second fugue in this piece is possibly the most thrilling and satisfying music Bach ever wrote for the organ. When the stop-and-start music of the French and Italian sections gives way to the four-on-the-floor strut of the fugue bassline—when the fingers and feet start to sail down the keyboards—when it all comes together, this music will just about take your breath away.

What do you play after that? Well, I’m not going to give the rest of the Clavierübung III here—we’ve already heard most of it, and the opening few chorales belong with Trinity Sunday and Pentecost—but these first two settings of the Creed are part of the answer.

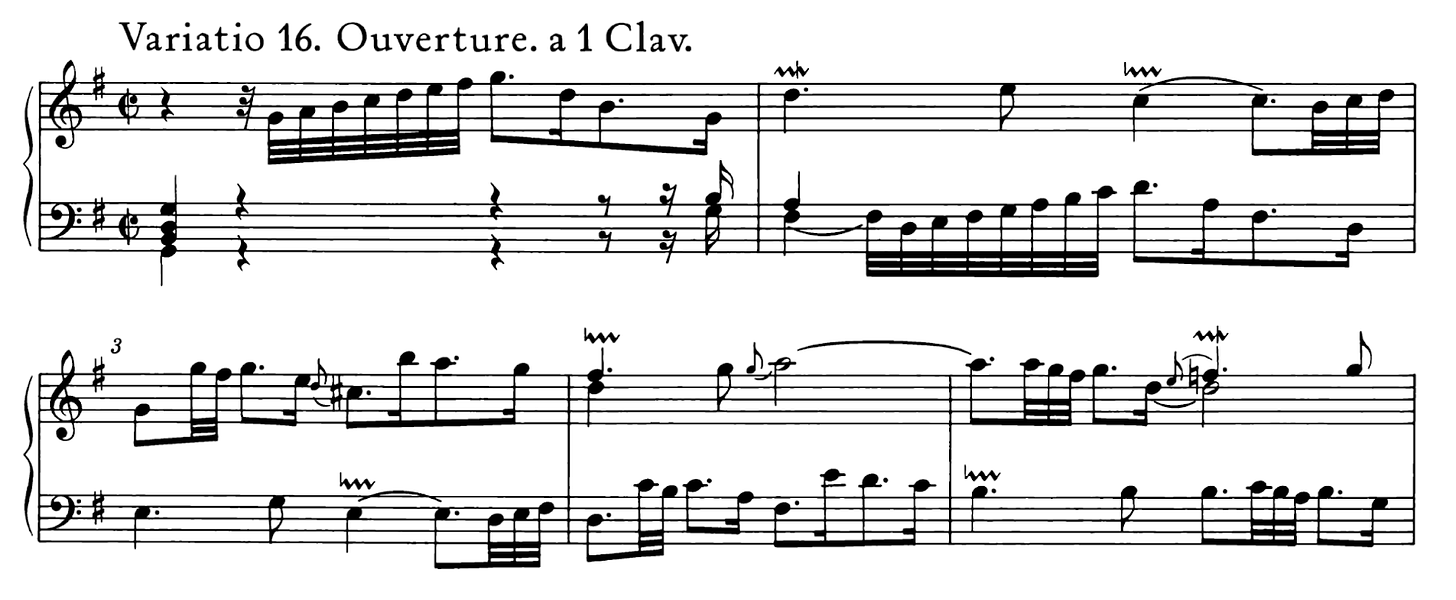

Funny enough, the two “Wir gläuben”2 settings from the Clavierübung illustrate exactly the same “national” contrast that we just heard in the E-flat-major Prelude. The pedaliter setting uses the same syncopations, running sixteenths, and ritornello format that we would associate with Italian style. And the fughetta looks even more like a French overture than the Prelude’s opening—just look at all these dots, thirty-second-notes, and little ornaments:

Standing at the exact midpoint of the collection, and the midpoint of today’s recital, it forms a perfect curtain-raiser for the second act.3

Now let’s play a game. Here are practice recordings of BWV 1098 and BWV 765, but I’m not going to tell you which is which:

This is what I’ll tell you: BWV 1098 (as the BWV number past 1080 indicates—are you getting the hang of this yet?) is a Neumeister chorale, a very early piece that was “rediscovered” in the 1980s. BWV 765 is a chorale that was copied out along with a lot of other Bach pieces as early as the 1710s, and a lot of other sources attribute it to Bach. Some scholars question this attribution; in the Bärenreiter edition of Bach’s organ works it gets relegated to Volume 10—the volume of “doubtful” chorales that has a nicely unbroken spine and clean, bright pages in most organists’ copies.

So you have two very, very similar pieces, both chorale fugues on the same tune, in the same key, and with more or less the same ideas. Both are formally a touch awkward or at least strange, especially when the texture clears out to begin a new phrase. And yet one is “doubtful” and the other fairly securely attributed to Bach. Can you tell which is which?

Is there anything better than the E-flat-major Fugue? Beside the Prelude, of course.

In some ways, the “St. Anne” Fugue (try singing along to “O God Our Help in Ages Past,” if you know it) mirrors the E-flat Prelude. It’s also got three parts (did I mention how hard people try to attach Trinitarian readings to the Prelude? Or the collection as a whole?). Its outer sections are also in five voices. And it also evokes a variety of styles, including French and Italian.

Still, the way in which the Fugue goes about its business is pretty different from the Prelude. Instead of interspersing the sections in a ritornello-like format, it proceeds cumulatively, in three distinct parts. It even changes time signatures and tempos between the sections, speeding up as the piece goes along—a pretty antiquarian way to structure a fugue, evoking pieces by Froberger and Frescobaldi (Bach collected music by both composers) from 70 or even 100 years before.

And the styles invoked are themselves quite different. First is a stile antico choral-style fugue, resembling stolid old-style movements like the second Kyrie, Gratias, Credo, and Confiteor from the B-minor Mass. Then there’s a completely new keyboard-style jig fugue in 6/4 and running eighths; it’s a big surprise when the initial fugue subject comes back, now twice as fast and in a skipping triple-time rhythm. But maybe it’s less surprising when Bach pulls the same trick in the last section, another jig. In the third section, the tune is actually at the same tempo as it was in the beginning (although in the sprightly rhythm of the second section), but now everything around it has now gotten 50% faster. And there are sixteenth notes, so it actually sounds 300% faster. The ending is a musical whirlwind.

Another way to look at this Fugue would be to note that Bach repeatedly makes you think that he’s done, and then proceeds to continue afresh. The opening old-style fugue is complete by itself, but nonetheless breaks out into the first jig. The jig completes what’s basically a whole fugue—as long as the opening section—before it restarts and the old-style theme comes bounding in. And even if the seam to the third section is a lot more papered-over—it begins on C minor, so you know that we’re not done yet—it in its own way contributes to this cumulative effect. Late in the fugue, Bach gives what sounds for all the world like its climactic moment:

Pedals storming down from the top of their range; keyboards screaming away at the top of theirs. The writing and rhetoric isn’t far off from the climactic moment of the Prelude, the part when the pedals suddenly broke out into running sixteenth notes.

And yet Bach finds a way to one-up this moment shortly after:

Notice that, in m.108, the top voice and the pedals are both playing the main fugue subject in quick succession, their rhythms trading off with one another—Bach has found a way to make two copies of the theme clearly audible despite being played in a fairly tight stretto. Then, immediately after shoehorning all of this into such a tight space, he clears the air, letting the 12/8 subject start afresh for one final time. Starting with just two voices bunched up at the top of the organ’s range, it takes four measures for the music to fill out the space below, to prepare the way for the pedals to pull the rug out from under us one final time. There’s nothing else quite like this passage in Bach’s other fugues.4 Scratch that: there’s nothing else quite like it, period.

Bach and Les Nations

I’m already verging on 3000 words about Bach here, so I’ll keep this short. Just as a postscript to the discussion of the E-flat Prelude, I thought it might be worth adding a little note about “national” styles in Bach.

The idea of German composers as “cosmopolitans” who united French and Italian styles isn’t a modern invention. It has roots even before Bach: Georg Muffat and Johann Jakob Froberger had already done trips around Europe and advertised themselves as great synthesizers of “foreign” traditions. And Bach himself was clearly into the idea. Forget about just France and Italy, either—consider the movements of the Flute Partita BWV 1013:

i. Allemande [German]

ii. Corrente [Italian]

iii. Sarabande [French]

iv. Bourrée Angloise [English]

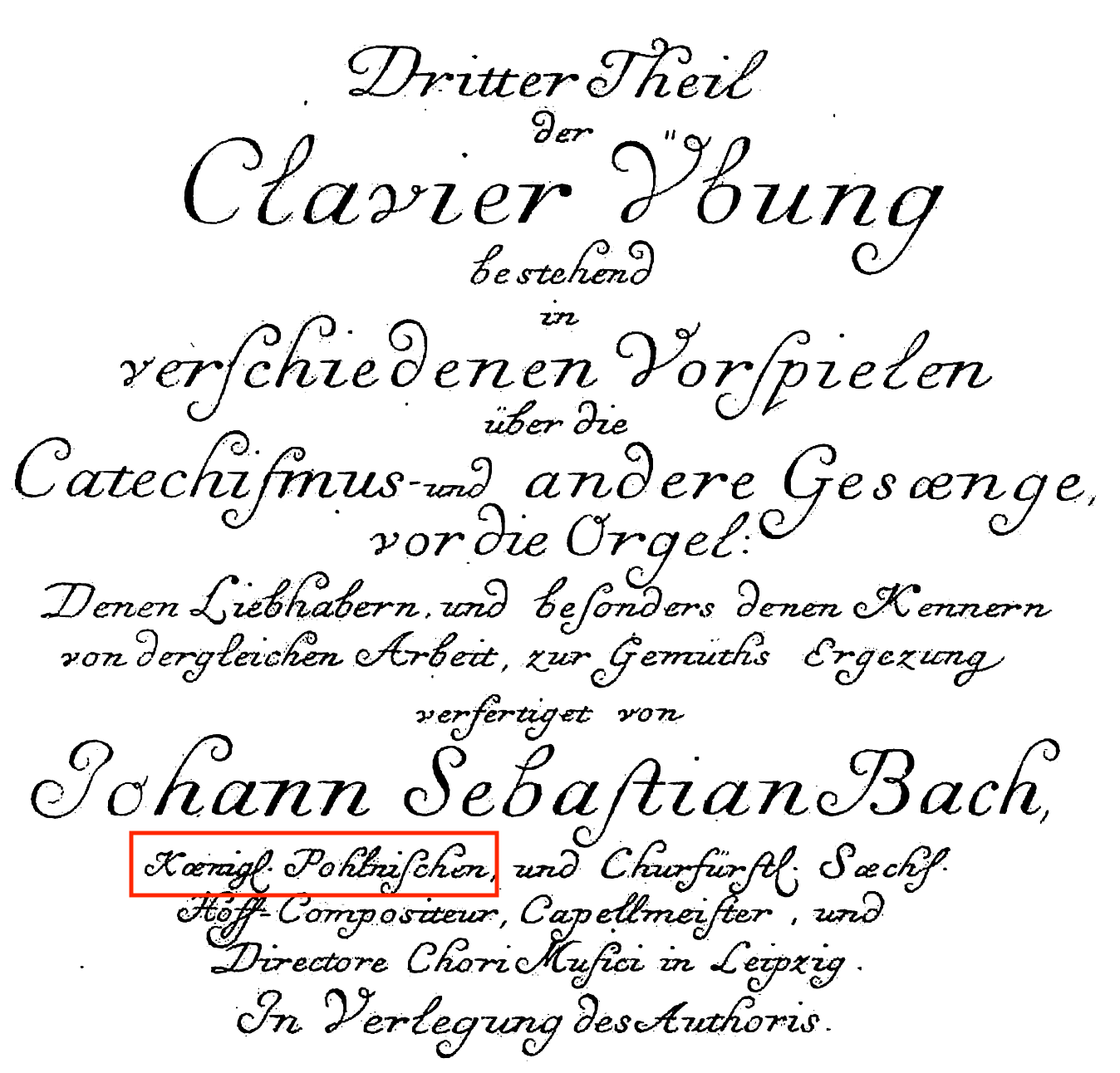

Elsewhere (the most famous example is probably the first Brandenburg Concerto), he even invokes Polish music. It makes sense: Bach worked hard to get an appointment as Royal Composer for the Polish court, and he advertised that position first on the title page of Clavierübung III:

And yet, as interesting as it is that Bach was influenced by Polish and English styles, it would be crazy to give them the same centrality as French and Italian music for his output. To say nothing of the German traditions he was raised in.

I don’t think anybody’s in danger of trying to put all the nations on a level playing field for Bach, but I have noticed something like this tendency when people discuss and present his organ music. For instance, at face value, Kimberly Marshall’s recordings of “Bach and” his Italian, French, and German precedents would seem to present the three traditions on equal footing. I doubt that was actually her intention (and they’re great recordings!), but it’s easy to see how the “one CD per country” format could be misread. Certainly, it’s awfully common to hear organists wax on about how Bach’s “fusion of French, Italian, and German” styles is one of the key manifestations of his “greatness” etc. etc.

It’s undoubtedly really cool that there are pieces like the E-flat Prelude which integrate the three “main” national styles so seamlessly, but that’s actually quite rare among Bach’s organ pieces. And when contextualizing Bach’s organ music, there’s something of a desire to see all three as pervasive—but they’re not.

Of course, I doubt anybody actually thinks that all three styles are exactly equal in importance for Bach’s organ music, for the simple reason that he was a German composer and very clearly works within German organ traditions. From the forms and registrations he uses, to his use of the pedals, Bach never stops being a German composer. And as I pointed out above, even his “cosmopolitanism” itself was German-coded in the 18th century. (Although French composers like Couperin could also write pieces like Les Nations and Les gôuts réunis.)

But even when just talking about French and Italian styles, their prevalence is nowhere near equal in Bach’s organ music. The influence of French organ music, in particular, is pretty limited in Bach. French music in general was obviously massively important, especially in his writing for harpsichord. But on the organ? There’s a couple of style brisée passages scattered around; the highly ornamented style of the two big C-minor Fantasies; the Pièce d’orgue; the theme of the Passacaglia (derived from a piece by André Raison); and of course the outer sections of the E-flat Prelude. That’s not a complete catalog of French influences, but it’s not all that far off.

Italian influence, by contrast, is everywhere in Bach’s organ works after the 1710s or so. You can see it practically anywhere you look. Let’s not even count the concerto transcriptions. You’re still left with pieces like the trio sonatas (and other trios), the Frescobaldian Ricercar/Canzona style of the “St. Anne” Fugue, and especially all of those preludes or toccatas and fugues that adopt Vivaldian styles. If you’ve been reading along, you’re probably sick of me making Vivaldi comparisons. I’m not saying that my notes are entirely representative, but the relative proportions are pretty noticeable.

In other words, the E-flat Prelude, with its full integration of all three styles, really is an outlier among Bach’s organ works. At the very least, it’s an unusually “French” piece. It’s important not to take it as representative of how the “national” styles operated in Bach’s organ music; but at the same time, that’s part of what makes it so special. If only he’d brought the English and Polish styles in too.

What I’m Listening To

Leyla McCalla – Sun Without the Heat

Leyla McCalla has a new album—that should be all the encouragement you need. Listen to it.

OK, I can say a little more than that. McCalla is another of those “Americana” historicist artists, like Allison Russell and Brittany Howard, and now Beyoncé. After starting out with the Carolina Chocolate Drops, her early albums were lovely folk and bluegrass projects featuring prominent banjo and cello. They also drew prominently on Haitian musics, both learned from her family and gleaned from archival research: 2022’s Breaking the Thermometer originated in a commission from Duke University to go through their Radio Haiti archives.

In some ways, the sound of Sun Without the Heat sounds like a continuation of Breaking the Thermometer, which branched out into a broader variety of popular music styles. On the other hand, it’s a pretty serious departure, with much less banjo, cello only featured in the final track, and significantly less foregrounding of Haitian Kreyòl. Instead, there are a whole range of Afro-diasporic musical styles: Afrobeat guitars (“Take Me Away”), Ethiopian tunes (“Love We Had”), Afro-Cuban tumbao (“Tower”), Brazilian Tropicalia (“Love We Had” again!), and others. There are also songs in a more stripped-back folk style (title track).

And then there’s a song like “Tree,” easily the highlight of the album for me. Beginning with a languid showcase for McCalla’s vocals, it moves to a shimmering surf-rock-like groove, before breaking out into an absolutely scorching guitar solo. Things only get wilder from there. You should listen to the whole album, but definitely give “Tree” a go.

Fred Hersch – Silent, Listening

Fred Hersch is obsessed with the sound. That doesn’t always work in his favor, since sometimes it feels like he’s more concerned with making the piano sound great than with making great music.

This album reflects the same obsession, but the results are much more musically interesting than usual. The standards are very pretty indeed, and they frame the album—it opens with the Ellington/Strayhorn “Star-Crossed Lovers” and ends with Alec Wilder’s “Winter of My Discontent,” and both are beautiful and sensitive, if sparse renditions.

But it’s Hersch’s compositions and improvisations that really make the album for me. He just sounds much more involved and engaged in harmonically jagged tracks like “Akrasia.” You can hear him having fun with extended techniques (damping and plugging the strings) throughout, in addition to more “traditional” play with musical materials (messing around with thirds at the beginning of “Starlight”). It can be a little bit abrupt going from Hersch’s numbers to the standards, but the transitions mostly work. The sound brings it all together.

Paul Van Nevel and Huelgas Ensemble with Jos Immerseel – Max Reger: Melancholy (Vocal Works)

Not every new release has to be a “revelation” (send me nasty emails if I start lapsing into clichés like that), but this one really qualifies. Sometimes Max Reger can remind you that he’s actually a pretty good composer, and this choral music (completely new to me) is some of his best.

Reger’s problem was never technique. He really understood what makes music tick—the little book on modulation is a great read—and knew the music of the past as well as anybody. His pieces are full of complex harmonies, dense counterpoint, and virtuosic instrumental technique.

No, Reger’s problem is usually that he goes completely and utterly overboard, to the point that words like “tasteless” start to feel like a massive understatement. A classic Reger score is a thicket of sixty-fourth notes with dynamic markings like ffff. (His letters, wonderfully, are equally dense with parallel lines: he liked to triple- and quadruple-underline phrases for EMPHASIS.)

But there are musical situations that make that kind of thick, flatulent writing impossible, and Reger actually really shines in them. The music for solo violin and solo cello falls into that category; so does (for no obvious reason) the clarinet quintet. And, I think that’s what’s happened with this choral music. It’s impossible, for instance, to make your harmonies too over the top when you’re limited to a strict number of parts. (Unless, of course, you’re a K-pop producer with infinite multi-tracking at your disposal.) Instead of sounding bombastic, meandering, or jarring like Reger’s chord progressions do, the writing in these pieces often sounds mysterious, fascinating, or (dare I say it?) just plain pretty.

I also get the nagging suspicion that part of what makes this album work is that it’s not entirely authentic in terms of performance practice. Sure, Van Nevel and Immerseel are historically-informed performers with sterling credentials, but Huelgas in particular focuses almost entirely on older music. (The name of the ensemble, after all, comes from a 14th-century manuscript.) On this album, te singing is light, smooth, and fluent in ways that I’m not entirely sure match early 20th-century German style; it sounds basically identical to how they sing Richafort.

I’m not saying all Reger performances should try this kind of ahistorical style, if that’s what it really is. Certainly, “light, smooth, and fluent” would sound just terrible for a lot of the orchestral and organ music; there’s nothing worse than Reger organ music being played on wimpy instruments or registrations.

But maybe people could try it? I can definitely imagine that some of Reger’s leaden sound is an artifact of performers not doing their best to lighten the music up. Give it a go: if the results are anything like this, it might even revive his reputation.

YUQI – YUQ1

Nobody does it quite like Song Yuqi. As she brags (and she, or at least her idol persona, loves to brag), she can pull off just about any concept. And so, even if Yuqi may never have lived outside China or South Korea, she’s managed to make the best SoCal-themed album in years. (To be fair, what is SoCal if not Chinese and Korean?)

I’m only sort of joking. Obviously the video for “Could It Be” is almost parodically L.A.-coded, and of course “On Clap” has a shoutout to her “hometown” Lakers legend LeBron. But there’s also the Hollywood lyrics of “Freak” (whatever “she’s Drew to my Barrymore” is supposed to mean, she’s also “lookin’ like a movie” and completely bought into car culture), and just a general vibe about this album. It’s probably also a factor that something like 90% of it, including all of both singles, is in English. (There’s a little Korean on the second two songs, but no Chinese anywhere, even when Yuqi brings Lexi Liu onboard.)

Regardless of unifying concept or theme, this is a remarkably cohesive and well-executed pop EP. It has some of the best harmonic sequencing I’ve heard in a while: the first three songs flow so naturally in part because they’re in F, F, and D minor, and “Everytime”—a C-minor song that constantly returns to its opening A-flat-major chord—goes perfectly before “Could it Be,” a song actually in A-flat. The songs adopt a variety of styles: disco-Britney5 on “Red Rover,” shouty midtempo pop-rock with rapping (say that three times fast) on “FREAK,” club hip-hop beats in “On Clap,” and nostalgic pop-rock everywhere else. But they’re sequenced cleverly to avoid anything sounding too jarring or samey.

The best songs—most of the album, really—deliver in spades on rock-solid fundamental pop songwriting: great hooks, beats, and harmonies, and no messing around. “Red Rover” is stupidly groovy, and full of nice little touches. The backing vocals in the prechorus! The funk bass in the chorus! That quiet little guitar lick that drops in and out unpredictably! The singalong final chorus! Why wasn’t this a single!

Then you have songs that make their bones on clever harmonic design. That includes the nice Dorian chord progression of “Drink It Up” (another great disco-funk chorus), borrowed straight from Yuqi’s 2021 single “Giant.” (She has songwriting credits on both.) But I especially mean “My Way,” a song that inexplicably seems not to have gotten much attention. (I’m about to write an excessive amount about this song’s chords, but rest assured that the tunes and instrumentals are really good too, if you care about that kind of thing for some reason.)

The verses of “My Way” follow a somewhat common pattern by leaving out the tonic, the home chord of the key; instead, the progression circles around and around without resolving: IV-vi-V-iii forever. These chords don’t point anywhere in particular, leaving the music feeling restless, up in the air. Then—this is probably the coolest trick on the whole album—for the prechorus, they use the same chords, but starting on the second measure: vi-V-iii-IV. Now the second measure of each pair is a chord that could plausibly lead back to I; the harmonic progression starts to feel more organized, more urgent. It’s also played twice as fast.

All of this makes it incredibly satisfying when the chorus comes in and finally gives us our tonic chord, our I. The rest of the chorus’s chord loop reorganizes the prior chord progression: I-iii-vi-IV. To put on my music theory hat for a moment (“he’s only saying that now?”), that progression begins with three successive chords that have a tonic-like function, but only one of them is the major tonic; the other two are minor substitutes. And the cadential chord that leads back to I is the relatively weak IV; V has been dropped from the progression. The overall result is an incredibly nostalgic, or even sentimental sound; you might know it from music by Brahms and Dvořák. If you like the Trio from Dvořák 8, you should love this chorus—same idea. But, like the symphony movement, it wouldn’t have nearly the same effect without having been prepared by the verses and prechorus.

You can really notice the difference by listening to “Could It Be,” a song that uses almost the same harmonic vocabulary but sticks to the same four-chord loop for the entire length of the track. “Could It Be” thus doesn’t have the same kind of arc or impact, instead drifting lazily along and letting the arrangement and tunes do the heavy lifting. Luckily, “Could It Be” excels in both areas. There are tons of wonderful details (here we go with another litany): that “The Less I Know the Better”-style bass in the verses; that little synth tune in the prechorus; that white-noise synth sweep that leads into the chorus; that harpsichord-esque synth that animates the chorus itself; the way the beat drops out to open in the second verse and last chorus; those harmonies that are layered in for the later choruses (apparently a difficult addition—this is one of the few times I’ve ever seen Yuqi say she’s not good at something). Like so much else on this album, “Could It Be” is simply perfect pop songwriting. Maybe Yuqi was right: we should just give her all the lines.

Also liked…

Ghost Note – Mustard n’Onions

Jean-Guihen Queyras with Gustavo Gimeno and Orchestre Philharmonique de Luxembourg – Dutilleux: Tout un monde lointain – Symphony No. 1 – Métaboles

Ann Savoy – Another Heart

David de Winter and The Brook Street Band – A German in Venice

Various Artists – Әlşәy: Bashkir Music

High On Fire – Cometh the Storm

What I’m Reading

I read contemporary poetry at a snail’s pace of one or two books a year. I’m glad that I made one of them Cindy Juyoung Ok’s Ward Toward.

Your mileage is really going to vary with this book. You may feel, for instance, that it can get excruciatingly on the nose with its major themes.6 There are multiple poems in the shape of psych and hospice wards (get the title now?), the explicitly intersectional despair of “In Atlanta,” and a poem literally called “Before the DMZ” in the shape of the Korean peninsula. I cringed a little bit when the book opened with the line “How dare you question my Eastern mystical status.”

I still think it’s a bit of a bad choice for an opening, but the other poems have a lot going for them. If you actually read “Before the DMZ,” you’ll see the work the 38th parallel does within the narrative arc of the poem, the degree of fine control that’s required to make its plot pivot at just the right point. And even if you’re not impressed with diction like “my beautiful / and disposable body, effortlessly endable” from “In Atlanta,” you’d have to be very grouchy indeed not to appreciate the play of images (colors) in lines like:

That winter, the city was a shock

of snow and she wrote asking for tips

on uncovering her paled car. She had

told us already of the kind of white hoods

that march, how she had watched

outside church at seven in black pigtails.

(Not to mention the gentle parallelisms and alliterations that animate the writing.)

It’s this virtuosity that probably won Ok her publication with Yale Younger Poets, the reason she seems to have impressed Rae Armantrout (a poet with a penchant for flashy forms herself). It’s on display throughout the collection; some of the poems really go all in on formal devices. “The Orders” is an Oulipo-esque poem where you can read line-by-line or choose to skip to the same-numbered line in the next stanza. “Ten Sessions” is a Mallarmé-esque cut-up of notes from her therapist. “The Five Room Dance,” probably the most “technically impressive” poem in the book, is a tightly-wound sonnet. And I’ve already mentioned the calligrams. Even if you’re not in it for the themes, you well may appreciate the technique.

In other words, even if it’s easy for me to imagine disliking this book, it’s also hard for me to imagine there not being something in it for everyone. After all, it’s kind of like if Apollinaire and some of the Language Poets teamed up to write a Korean-American version of Life Studies. That’s an insane collision of ideas, and it’s kind of an insane book (Ward). But there’s an incredible amount of talent on display, and you’ll almost certainly find something in it to treasure. I’ll look forward to making Ok’s next book one of my two in a future year.

A few others:

Financial Times – A disappearance in Xinjiang: What became of famed Uyghur academic Rahile Dawut?

Allure – How Far Would You Go to Track Down a Discontinued Beauty Product?

Fangraphs – Whitey Herzog Defined an Era, but He Was Ahead of His Time

Atlas Obscura – Japanese Green Tea Once Fueled the Midwest

Rest of World – Inside TSMC’s Phoenix, Arizona expansion struggles

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

And yes, potentially to avoid repeating a key from the Six Partitas.

I don’t know why Bach adds the umlaut either.

Note that the example above, Goldberg Variation No.16, is also a French overture at the midpoint of a piece. Bach does the same trick to open Partita No.4 (out of 6) as well; clearly it was an idea he liked.

Although, interestingly, those two early “Wir glauben” settings do do something pretty similar, albeit on a much smaller scale.

The opening piano-snare combo is right out of “...Baby”/“Oops”; the disco part is self-explanatory.

Although the words “Korea” and “Japan” are very pointedly omitted, to an extent that can almost feel awkward or mannered in the collection’s last poems.

you have dropped a lot of interesting tracks there...and yes...Reger Choral Music? Those of us who are addicted to things like Brahms Motets and Mendelssohn Psalm settings will tune in...