Week 6: 6 November 2023 – Trio Sonata No.6 and Trinity 23

Plus: What should arrangements sound like?, TAEMIN, Christoph Wolff's latest, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

This week, I’ve been listening to some musical projects by Ho-Chunk elder, activist, and historian, Andrew Thundercloud. Especially moving is a song telling the story of Ho-Chunk code-talkers during WWII—a nation(s)-wide project that’s still so often made entirely about the Navajo. You can read more about the song and the history here.

Week 6: 6 November 2023 – Trio Sonata No.6 and Trinity 23

Please save applause for the end of each set

Prelude in E, BWV 566

In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr, BWV 712

In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr, BWV 640

Trio Sonata No.6 in G, BWV 530

i. [Vivace]

ii. Lente

iii. [Allegro]

Concerto in D minor BWV 596 (after Vivaldi, L'estro armonico, No. 11, RV 565)

i. [Allegro] - Grave [Adagio e Spiccato] - Fuga [Allegro]

ii. Largo e spiccato

iii. [Allegro]

If ever there were a Bach “Prelude and Fugue” that were an uncomfortable fit for the title, it would be this one. As I laid out in the discussion of Preludes a few weeks ago, this is a piece in the mold of the five-section North German Præludium; there are two fugues and multiple passages of “prelude-like” material.

That said, the surviving manuscript sources for this piece all include the heading “Fuga” only once, above the first fugue. Ignore the “prelude-y” section that follows: if you listen closely, you’ll hear that the triple-time, dance-like second fugue is based on a variant of the theme from the first—same repeated notes, same trajectory down a major triad. This is also a pretty common technique for the kind of North German composers that young Bach studied with: to take one example especially near to my heart, you can hear almost the same thing (down to the repeated notes in the fugue subject) in Nicolaus Bruhns’ Præludium in G.

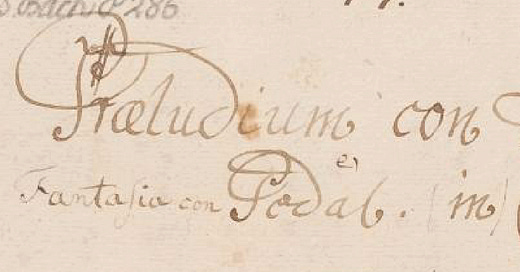

So maybe the use of the singular—“Prelude” and “Fugue”—is alright, if we think about the second fugue as a variation of the first. And the oldest surviving source says “Præludium con fuga,” which seems like a reasonable compromise. Just as Thomas Mann’s Dr. Kretzschmar says that the Missa Solemnis has “the Credo with the Fugue,”1 this can be a “Prelude with Fugue.”

….On the other hand, as you can see, this same source also says “o Fantasia con Pedal.” And alternate names abound for this piece. If you look for BWV 566 on IMSLP, you’ll find it under “Toccata and Fugue.” Wikipedia throws up its hands and says “Prelude (Toccata) and Fugue” Maybe it’s best not to obsess about these names if musicians in the early eighteenth century themselves barely seem to have cared.

Also: yes, it’s not a flourish of the pen—this manuscript says “Præludium…in C.” Not E.2 As far as I know, there’s not a single source from Bach’s lifetime that has this piece in E major. Meanwhile, the C major version has lots of nice, early copies from Bach’s students. Here’s the general consensus among Bach scholars, as given on Bach-Digital:

The version in E is the original (using a manual compass from D♯– b2), although copies only exist from after 1750. In the earliest source (after 1714), however, the work was transposed to C (with octave displacements) so that it could be played on an organ tuned in mean tone (authenticity doubtful).

As far as I understand it, this argument relies on two major premises (but I could be missing something):

Something like a version of lectio difficilior: E Major is the more unusual key, so it would make more sense for a copyist to transpose the piece away from this key than to it.

The octave displacements in the C major version are “more awkward” than their equivalents in the E major version.

I can’t say I’m all that persuaded by either of these. There are lots of pieces where a transposition would smooth things out in some passages, or where the purported awkwardness is just part of the writing. And there are lots of examples of Bach or later copyists transposing pieces to “rarer” and less in-tune keys: most famously, the French Overture (from C minor to B minor), but also probably BWV 552 (from D or C to E-flat by Bach) and BWV 545a (from C to B-flat by…who knows?).

So I think it’s entirely possible that this piece was put into E major later once organs became more widely capable of playing in that key. Why? Well, why not? It works well in that key, and a little variety is much appreciated among a sea of Preludes in C. And ultimately, that’s the key factor for me sticking to this version—even if the transposition isn’t by Bach, the piece is basically the same, and it’s nice to hear this kind of music fight with the tuning a bit for once.

In any case, assuming this was in fact an early “student” piece (it’s not just the octave displacements that can sound a little “awkward”), it certainly seems to have been designed to impress. Flashy runs in the hands; lots of showtime for the pedals; thick, thick writing that must have overwhelmed the wind chests of most organs; rhythmic subtleties that will put just about anybody on the back foot; and counterpoint that sounds almost as intricate as it is finger-twisting to play. As always, the fugue subject is a threat to the organist’s feet, and he makes them jog across all of those repeated notes, jumps, and awkward little runs for page after page. It’s significantly longer than any prelude by Buxtehude, and (as far as I can tell) much harder. What a little show-off.

Two chorale preludes on Psalm 31, about as different as they could possibly be. First, a sprightly jig, although a truly weird one: it’s hard to feel where the downbeat is, partly because the harmonies and lines are so strange. Then, setting the last line of the chorale—is it “Keep me in your faithfulness, my God” from the first verse?—the music suddenly explodes into a rush of sixteenth notes, with strangely poignant and intense chromatic harmonies. (Representing temptation perhaps?) Let me know if you come up with an interpretation, because this piece has had me flummoxed for years now:

It’s this darker, chromatic soundworld that the Orgelbüchlein “In dich hab’ ich gehoffet” inhabits. If you listen closely to the two pieces, you’ll notice that the tune at the top of the texture is quite similar (begins by going up a fifth, has the same habit of sliding down the scale), but of course the first one is major and the second is minor. Maybe the mood of this chorale prelude is what the ending of the other one is pointing to.

And now, here’s something we hope you’ll really like.

The wonderful (if incomplete) Netherlands Bach Society website has a great way of introducing this piece. They quote a 1788 letter (possibly by C.P.E. Bach) weighing in on whether Bach or Handel was more “modern”:

Besides other trios for organ, there is a set of 6 such pieces for two manuals and pedal, which are so elegantly composed that they still sound good today and never age, and will survive all revolutions in musical taste.

Out of the entire corpus of Bach’s music (and if it really was Emanuel Bach writing, he would know better than most!), the author picked these trio sonatas to illustrate how up-to-date Bach could sound. At that point, the trio sonatas weren’t among the large and growing list of Bach keyboard pieces that had been published; were readers supposed to know these pieces, or at least feel like they ought to know them?

In any case, it’s clear why these pieces sounded “modern.” In fact, they’re so fashionable that they almost break the mold of what a trio sonata had traditionally been. Take the movement structure: fast-slow-fast. That’s the format of a Vivaldian concerto (although ironically not of the actual Vivaldi concerto that’s coming next), not a Corellian trio sonata, which would normally go slow-fast-slow-fast. And the writing itself is much closer to the younger generation of Italian composers: sequences populated by “mechanical scrubbing” abound. (And do I ever love those sequences and that scrubbing!)

This trio sonata in particular, the last of the set, is even more fashion-forward. The first movement is in the trendy time signature of 2/4, and it begins with the two upper voices in unison, something that sounds too hip even for Vivaldi. Maybe 1730s Telemann could have written this opening; Corelli would never have dreamed of it. And Handel never strayed far from Corelli; Emanuel Bach (or whoever) had a point.

This is also about as much fun as Bach ever has with a pedal part. It practically bounces all over the pedalboard in the first movement, a really joyous and lighthearted experience. Just like the first trio sonata, the pedals get to take a turn playing the tune in the slow movement. And they’re even more mobile practically throughout the last movement—although here the experience is a bit less “jaunty” and more “contortionist.” There’s a reason these pieces were used for teaching more than performance for so long. It takes an awful lot of work to get comfortable with them.

I get asked fairly often: “What’s Bach’s hardest organ piece?” Of course, the answer depends on your technique, your interpretive decisions, and to some extent on the organ. There are a lot of possible answers, and I can see the case for all of them. And really, it’s not a particularly fair question, to begin with—

I’m just kidding, it’s this piece. This is the toughest one. I have a really hard time imagining otherwise.3 It may not be the most complicated pedal part in the word, but right from the beginning, you’re asked to play this incredibly ungainly series of repeated notes:

It’s an ingenious way to arrange what would otherwise be a death-defying series of leaps in the hands—but it still remains almost impossible to play evenly as written. (Like—I think??—most organists, I’m cheating a bit by playing it down the octave on a 4’ stop. But Bach had that option too…)

Then there’s the fugue, filled with absurdities like this:

This is all technically playable (I’m not skipping any notes!), but it’s at or past the limit of Baroque keyboard technique; the fast flourish at the end just adds insult to injury. And he doesn’t simplify at all when the three soloists go on their flight of fancy at the end:

Again, it’s actually quite smart (you can grab enough notes in the left hand to avoid a fully Lisztian series of thirds and sixths) but it’s desperately uncomfortable.

And the same all goes for the last movement, which piles on with a full page of quick repeated notes that have to be executed evenly:

Before going completely off the deep end with wrist-breaking ensemble writing:

Look, I don’t know every keyboard piece from Bach’s time and before, but I’m fairly confident that nobody had ever written for the organ like this before.4 And really, very few composers have written repeated chords like this since either. There are studio recordings by extremely accomplished organists (who I respect too much to name or link to here) that trip up on this passage. Hopefully I’ll be able to do better on Monday!

Still, difficulty is really a sideshow here. This is a great concerto, vintage Vivaldi. The fugue is a nice, relaxed contrast from Bach’s uptight, Germanic style of counterpoint. And it’s a whole lot of fun to be able to bring these string effects across on the organ, to be able to play music like this at all. No wonder the experience of making these arrangements changed Bach’s style forever.

Make It Sound Like the Original

Why did Bach make the D-minor concerto so hard?

Maybe it was fun for him too. It could have been fun to play (if he ever had the practice time to really be able to nail it—“you can write this stuff but you can’t play it”?). But also fun to write or figure out: “oh, I can make that work on the organ too!” That’s also a kind of showing off, and we also know how much of that there is throughout Bach’s organ music too.

To get away from this kind of psychologizing a bit though: there’s also a perverse kind of literalism in the concerto arrangements. Long strings of quick repeated notes are not organ writing; I pointed out a few weeks ago how even a short, slower passage of them (in the Neumeister “Durch Adams Fall”) stands out like a sore thumb among Bach’s organ works. Making the pedals hammer on a single note for a whole movement is a great way to sound like Vivaldian strings, but also completely unlike anything else an organ composer would ask you to do. And refusing to simplify the thickets of parallel thirds and sixths seems like an almost pointed gesture: if you can play these notes from the original, you should.

To put it another way: not only does this kind of writing ignore the comfort of the player, it ignores what “sounds best” on the instrument. The technique needed to play these passages at a reasonably Vivaldian tempo often risk producing harsh sounds, where the initial “chiff” of the wind entering the pipe dominates, or where the pipe doesn’t quite “speak” its pitch fully. It’s the kind of thing many organists will bend over backwards to avoid: according to them, you simply have to play it at the tempo and with the articulation that allows every note to speak fully.

I’m not so sure. String players, especially those trying to evoke Baroque styles, are perfectly happy to let unstressed notes “poof” away, or to really hack at the strings when the style and rhythmic effect call for it. (And of course players on plucked string instruments are completely used to sometimes letting the strumming do 99% of the work and almost disregarding the pitch.) I’m not saying anybody tries to make the ugliest sound possible, or doesn’t want listeners to hear the notes; but sometimes the “ugly” sound is much more effective and exciting in context. I absolutely love how Elizabeth Blumenstock and Alana Youssefian are willing to scrub and chop at their instruments to bring across the drama of Vivaldi:

Does that mean this style is more “Vivaldian”? It’s hard to say, although for me it helps match some of the surviving descriptions of the kind of flair Italian Baroque string players played with. I would love my Vivaldi to sound more like that, in any case.

On the other hand, Bach never met Vivaldi. I’m not even sure he would have even met an Italian musician by the time he did these arrangements. If we’re trying to figure out the appropriate style for playing his arrangements, shouldn’t we try to play them in a “colder” Germanic style, if not a fully “organ technique”-based one?

Honestly, I also get the feeling that such differences might also be pretty overrated. Never mind that German courts, like those in England, Russia, and elsewhere, were constantly importing Italian musicians (and painters, and architects, and, and…).5 Eighteenth-century musicians were much more mobile than we sometimes like to think. You don’t have to be Handel or Farinelli gallivanting across Europe to make a couple trips from Naples to the Dresden court, and musicians went abroad to study then just as now. Especially Germans. I don’t think that we get to assume that Weimar musicians in 1708 would have had no idea what to do with newfangled Vivaldi concertos, and I definitely don’t think we can just posit that they slowed them down and straightened them out.

And the same, I would say, goes for the organ. There are limits—I physically can’t play this piece quite as fast or stylishly as my favorite string recording. In any case, my point isn’t about trying to win races or inverse beauty contests, just trying to get a little more inspired by the sound of a string ensemble before circling the wagons around “this is organ music, so we must respect the organ.”

How about the trio sonatas then? It seems almost an article of orthodoxy among Bach scholars by now that these pieces were at least mostly arranged from preexisting instrumental works by Bach. I’m really not sure about this hypothesis. All six are both less awkward (despite my complaints about the pedal part in the last movement of this sonata) and less obviously “simplified” than, for instance, the “Bach circle” organ arrangement of BWV 1027/1039. Conversely, string ensembles playing these pieces do have to do some adjusting to make them work out; as written, they would only fit the unheard-of ensemble of violin, viola, and continuo. And, frankly, it’s hard for me to imagine Bach wanting to write such idiomatic virtuoso pedal parts (last movement of Sonata No.5, first movement of today’s sonata) for cello purely by accident.

Still, I think these pieces could also use a little bit of string inspiration. Maybe not hacking and chopping, but bowing, dynamic contrast, and phrasing in the pedals. Let’s not let the violinists own this organ music; we have Vivaldi to steal from them.

What I’m Listening To

Sofia Kourtesis – Madres

This album’s been reviewed in a lot of places, and quite favorably, so you can read any of those to learn about Kourtesis (Peruvian, based in Berlin) or the album’s context (the anti-homophobia chants sampled on “Estación Esperanza”; who “Vajkoczy” is and his relationship to the artist).

What I will say is that this album has something for just about everyone. Sure, it’s all house music of some flavor, but it ranges from utterly warm, sweet, and generous (“Madres”; “How Music Makes You Feel Better”) through more straightforward nightclub-y stuff (“Habla con Ella”; “Si Te Portas Bonito”) to chilly experimental sounds (“Moving Houses”) to the harsh, noisy world of “El Carmen” and “Estación Esperanza.” Couple that with Kourtesis’s soft, dreamy singing and amazing ear for gorgeous synth sounds, and you get a really lovely and stirring homage to motherhood. It grooves pretty hard too.

Vanni Moretto and Atalanta Fugiens Orchestra – Sinfonie Milanese after the French Revolution

OK, on the other hand, this album probably won’t get a single review.6 Unfortunately, I’m not particularly well-equipped to tell you about any of these composers or performers—if you already knew “Bonifazio Asioli,” I hope you either have tenure or a really great therapist. (Although Giuseppe Gazzaniga, best-known as the composer of the “other” Don Giovanni, is maybe having a moment right now.)

Why bother with this music then? For starters, these are pretty great performances. The players are uniformly very good and cohere very well, and the interpretations are wonderfully dramatic, full of dynamic and tempo contrasts to fit the swerves this music often takes. (The recording is also engineered quite well, giving both a sense of a huge space and extreme-close-up clarity.) The wind soloists really shape their lines well, all with a very nice sound. Basically: these musicians take this music seriously, playing with more intensity and engagement than a lot of famous orchestras bring to their “favorite” warhorses. It doesn’t surprise me to learn that Atalanta Fugiens’ interests range from Francesco Zappa to music in the Milanese ghetto. I just want to hear them play Joe’s Garage now.

And the symphonies themselves? I can only speak for myself, but I found them shockingly enjoyable (exciting? Sometimes beautiful? And full of surprises?), and frankly a few cuts above the “eighteenth-century filler” that you often hear on classical radio stations. But they’re especially interesting to me because they help answer the Italian side of a question I’ve always wondered about: crudely, “How did we get from Mozart to Berlioz?” The answer is not just “Beethoven,” and definitely not “Beethoven and Schubert”; and adding in Rossini only helps fill things in a little bit. (The real causes are probably the dual Industrial and French Revolutions—new instruments, growing mass audiences and publics—but composers still had to change styles in response to these factors.)

Part of the problem with trying to get a grip on this question is that you have to listen to composers like Hoffmann, Méhul, and Spontini; as far as I can tell, nobody’s tried to write a book that covers this ground comprehensively since Edward Dent’s The Rise of Romantic Opera. Dent died in 1957. But somehow recordings of this music—really good recordings—have sprouted up everywhere. The Palazzetto Bru Zane, for instance, has sponsored an incredible series of opera recordings that cover many of those composers. It’s amazing what taking these composers seriously can do for the music. Maybe La vestale still isn’t my favorite opera, but I no longer think it’s boring.

Then there’s recordings like this one. Asioli, for one, was born the year before Beethoven, and the F-minor symphony that opens the disc really really helps show some of the ways in which Beethoven was just following current trends in orchestral writing and symphony construction. The other symphonies help give something like a bridge from Mozart and Gluck to Rossini. And it’s all music that I actually find myself coming back to listen to on its own terms. Unexpected sentence: count me in for the next find from the Milanese archives.

Gafieira Rio Miami – Bring Back Samba

“Fun” is right. I’m not too familiar with gafieira in particular—it sounds to me like a “straightened-out” (whiter?) version of samba, which I guess is what it is—but this is definitely a great dance album, picking up a variety of Brazilian musical styles (chorinho doesn’t just crop up in the track named for it) and mashing them up into a distinctive big-band sound. Nice solos on “A Rã” and “Nó na Madeira” especially.

TAEMIN – “Guilty”

Maybe I’ve done a good job of disguising it, but I’m not a very good K-pop fan. I don’t collect photocards; I don’t typically buy multiple versions of an album. I don’t post on Twitter/X at all. I don’t watch dramas, even if they star artists I like. I haven’t started buying Blackyak or New Balance (yes, people actually do this). And, truth be told, there are groups whose music I like where I can barely tell the members apart (sorry Dreamcatcher) or, frankly, where I’m not confident I could even name a single member (sorry TREASURE).

But my biggest failing as a fan is surely that I can’t dance or remember almost any choreographies. Really: I can’t execute almost any of the JYP “basic dance.” And I generally prefer listening to watching music videos. That’s a problem—as Giselle put it: “What we say in Korean a lot is “Music you can see.””

I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered another kind of music where people will so routinely say “This song is so. good. The video, the choreo, the visuals…” Obviously there are American MVs/dances that partially define a song’s identity. But it’s not nearly as pervasive. Watch how fromis_9’s Nagyung (and then Jiheon) identifies “FEARLESS” when Eunchae asks her to name her favorite LE SSERAFIM song:

No singing, just the move for “Watcha lookin’ at” from the song’s chorus. This is not the absolute most iconic dance of all time, and it’s also not an “iconic” representation of the song’s title, unlike, say—

—(TWICE, “TT”), or even

(STAYC, “Bubble”). Still, for a huge number of lead singles, the song is basically identifiable by the choreography or even just one key move. Or the story in the music video: if you asked most fans to talk about the meaning of After School’s “Shampoo,” BTS’s “Spring Day,” or IU’s “eight,” their response would probably make almost no sense without the music video.7

But I guess everybody already knew that choreo and MVs can be more important than songs in K-pop:

Aside from PSY, I’m not sure if there’s another solo artist (or group as a whole) who’s more identified with his dancing than Taemin. He had to be a good dancer: SM Entertainment was originally so underwhelmed with his singing that, in SHINee’s debut song, Taemin (at the age of 16) wasn’t given a single line. It’s really a testament to his famous work ethic (and SM’s vocal training staff) that he’s now making the rounds of “voice-only” music shows.8

But still, if you say “Taemin” to a K-pop fan, they’ll say “MOVE,” and they probably won’t mean the music itself:

—and yet, they (I) will also probably say that this is a really good song. I listen to it far more often than I watch the MV. (And not just because Momo now owns this choreo.) What does it mean for a dance or video to contribute to a song when we’re not even watching it?

I’m not a MV scholar, and I’ve already told you that I’m not super qualified to talk about dance. But let me take a stab at it. Sometimes, a super-iconic dance can liven up what is otherwise a less interesting part of a song. I think I’d probably be bored with the first verse of ITZY’s “WANNABE” without Ryujin’s shoulder dance, which is impossible to disentangle from this music:

I can’t hear these lines or this beat without visualizing or feeling this move (not that I can pull it off!). On the other hand, when some of their more recent songs begin with the same kind of verse but lack the choreo…I want to skip the song.

Other songs have a choreo that enhances the overall vibe or soundworld. The “horse riding” from “Gangnam Style” surely falls into this category; it has nothing to do with the lyrics, and it accompanies what’s already one of the catchiest parts of the song, but it definitely ups the silliness quotient. I’d also put GFRIEND’s choreography, especially “Rough” in this category:

GFRIEND’s almost creepily good synchronization (maybe not the only creepy thing about this video) and these smooth ballet-like moves are a perfect match for Iggy & Youngbae’s distinctive production style, which blends sweet harmonization and classical-esque orchestral gestures with disco beats. I can’t hear this song without seeing these twirls, and the song is better off for it.

Of course there are songs (like “TT” and “Bubble”) that use the choreography to illustrate the title word. You probably know the finger-guns in the chorus of BLACKPINK’s “DDU-DU DDU-DU”:

(I prefer Chuu’s version.)

And then there’s Taemin.

Taemin’s moves are definitely more abstract than “TT” or even “horse riding,” but they also don’t exactly substitute for musical interest like Ryujin’s shoulder dance. They’re also less generalized than the pirouettes in “Rough”: I think what makes “MOVE” in particular (but really all of his choreographies) work so well is that each move is keyed in so precisely to what’s happening in the music. His tortured9 stretching-out, sudden popping and locking, bizarre angles, dropping to the floor, hip swivels, grabbing his face—each gesture is directly linked to a musical event with the same emotional significance. Stretch out for a long, pulsating note in the synth; snap up when the beat swells or rises; match everything precisely to the rhythms of both vocals and instrumentals. You can almost hear the song from the video alone; and you can almost feel the choreography from the song, even if you’ve never seen it.

None of this is easy. K-pop idols practice dancing a lot more than they practice singing. Recording the actual song takes a couple days, and the music is rarely rehearsed vocally; the choreographies, on the other hand, still need to be rehearsed for hours each day, for as long as they’re being performed. GFRIEND’s synchronization was hard-won: the rehearsal schedule for “Rough” was so intense that Yuju asked to have a wisdom tooth taken out—electively!—in order to get a couple days’ rest.

K-pop agencies understand that the visuals are part of the music. (The first hint should have been that groups have roles like “visual” and “face of the group” in addition to “lead singer” and “main rapper.”) Visuals aren’t just a form of advertising for the group, or even something nice that “goes along with” the song. An artist like Taemin knows that his song is only half-finished when it’s recorded. The dance and the music complete each other.

Also liked…

Titanic – Vidrio (really liked it but don’t have much of anything to say)

Quatuor Arod – Debussy, Atahir, Ravel (the Atahir is the highlight)

eite – “INDEPENDENT WOMAN” (shockingly good for such a random label/group!)

Shabazz Palaces – Robed in Rareness

Ragana – Desolation’s Flower

What I’m Reading

Don’t laugh—it took me this long to get to Christoph Wolff’s Bach’s Musical Universe (2020). I’m not a Bach scholar, so I don’t feel the need to keep completely up to date with the firehose of books and articles. (And definitely don’t quiz me on Bach-Jahrbuch publications!)

On the other hand, this isn’t exactly a book for Bach scholars. It’s a little bit hard for me to tell, but it really seems designed for, well, you, dear readers: this is a systematic overview of Bach’s works at a “mesoscale” level. Occasionally, you get short vignettes on individual pieces, movements, or passages. (Dare I say that the short Orgelbüchlein analyses reminded me of some of the writing I’m doing here?) But more often, the music is put into the broader context of Bach’s work as a whole. That’s the goal of this book: to try to paint a picture of Bach’s works to complement the picture of his life and personality given in Wolff’s biography The Learned Musician.

What are the key elements of this picture? Wolff introduces Bach’s music with two biographical vignettes: the triplex canon featured on his official portrait, and the list of works published in his obituary. Respectively, they illustrate Bach’s characteristic interest in counterpoint (which verged on becoming an obsession as he aged) and his interest in putting “greatest hits” within each genre into collections. (Or writing “greatest hits” books from scratch.) It’s a neat way to organize a book like this: the works list gives Wolff a source for what Bach’s family thought was his most important music, which he can use to structure his own account.

Wolff knows as much as anybody about Bach, and in particular the music; he’s said that his inspiration for becoming a scholar was watching Karl Richter conduct the Matthew Passion entirely from memory, and I’m sure that he has the piece (and many others) equally well engraved in his head. So when he makes claims about what is significant or unusual within Bach’s works, we should believe it. He also loves pointing out when Bach’s works are unusual within eighteenth-century music as a whole: which collections or pieces are biggest, longest, most complex. And, to be fair, Bach has a lot of unusual pieces; that’s a big part of why he’s been elevated to the status he has now. It’s good to have such facts pointed out by somebody who really knows what he’s talking about, even if he’s ultimately still trying to make a case for Bach.

A few others:

Harper’s – Forbidden Fruit: The anti-avocado militias of Michoacán

Common Edge – The Challenge of Creating a Women-Friendly Architecture School in Afghanistan

Human Transit – Basics: Why Aren’t the Buses Timed to Meet the Trains?

PNAS – Exposure to the Indian Ocean Tsunami shapes the HPA-axis resulting in HPA “burnout” 14 years later

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

Unaccountably changed to “the Credo with its fugue” in the John E. Woods translation; “Credo mit der Fuge” is the original, since I know you’re curious.

From the same diffident Wikipedia page: “in (C or) E major.”

Maybe the last movement of Trio Sonata No.2—depending on how fast you dare to play it.

You know you’re in bad company when the closest comparison is Alessandro Poglietti’s infamously insane Rossignolo—in movements literally called things like “Aria Bizarra.”

As much as people love to contrast the “French” and “Italian” Baroque styles, remember that Jean-Baptiste Lully, the founder of the former, had to learn French as a teenager and change his name from Giovanni Battista Lulli.

I was delighted to find this piece from UVA student radio about a previous entry in the project.

Although, Taemin isn’t the first dance-focused artist to appear on some of these: much as I like Seungyeon’s voice, KARA was not known for their singing, and watching them on Killing Voice was…kind of weird.

Especially appropriate for “Guilty,” which—if the music video didn’t make it obvious—is about being sexualized as a 16-year-old debutant. Think “Zezé” with dancing; and it looks like it’ll attract some of the same controversy.

EDIT: as usual, AsianJunkie has a good and detailed analysis of what’s going on.

he may not have heard Vivaldi but there was plenty of wild German and Austrian string writing (Biber) ...what do we know about the sound?

would you care to comment on dance's apotheosis?