Week 17: 19 February 2024 – B-minor Prelude and Fugue and Lent 1

Plus: "Prelude to What?" Part II, IU's Dandelion Spores, The Life of Music in South India, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

It’s not every day you see a musician advertise themself as specializing in solo viola and electronics. Then again, most musicians aren’t like two-spirit Anishinaabe composer Melody McKiver. You can get some sense of their soundworld from pieces like Odaabaanag, an Anishinaabe take on the premise of Steve Reich’s Different Trains; the same post-minimalist aesthetic shows up in their Reckoning EP (make sure you get to “Niswi” and “Naanan” in particular). But they also have some fascinating collaborations, not least “Runaway” with Frank Waln (who I’ve mentioned but not done real justice to here). And check them out on Marina Thibeault’s Viola Borealis album: McKiver’s work makes the Telemann concerto look pretty pale by comparison.

Week 17: 19 February 2024 – B-minor Prelude and Fugue and Lent 1

Please save applause for the end of each set

Prelude and Fugue in B minor, BWV 544

Canzona in D minor, BWV 588

Christ, der du bist der helle Tag, BWV 1120

Christ, der du bist der helle Tag, BWV 766

Fantasia (con Imitatio) in B minor, BWV 563

Fugue on theme by Corelli in B minor, BWV 579

It’s time to begin the Lenten season: no “chamber” music (trios or concertos), lots of somber chorales, and dramatic preludes and fugues in “harsh” keys associated with the Passion. I actually have no idea how much of that accurately reflects 18th-century Lutheran theology; I wouldn’t want to program purely on the basis of the modern (Catholic-inflected?) conception of lent. But it does at least match up with some knowable musical facts. Concerted music in Bach’s churches was indeed curtailed during Lent; good luck finding a Lenten cantata in his output.1 And we know the relevant keys (and musical formulas) from the two surviving Passions and the B-minor Mass.

Speaking of B minor. After the “Cathedral” Prelude and Fugue, this prelude and fugue was the first “major” Bach piece I learned, and I sometimes think it gave a misleading “first impression.” (I didn’t know the organ music particularly well at the time.) Partly because it’s a very unusual piece, and partly because…well, I thought they’d all be this good.

Several things make the prelude stand out from the pack. First of all, its intense, mournful harmonic language. The piece starts with a cry at just about the very top of the keyboard, and tends to descend via musical “sighs” (appoggiaturas and the like). And it’s full of jagged leaps, by tritones and other diminished intervals.

All of that sounds like the musical world of a particularly intense, slow chorale prelude like the Orgelbüchlein “Durch Adams Fall.” And yet it’s coupled with the dance-y time signature of 6/8, filled with thirty-second notes and oddly syncopated lines in the bass. All of that matches its Vivaldian ritornello format and propulsive use of sequences. In other words, while the piece’s use of harmony and melody tempts you to wallow sorrowfully with a slow tempo, its rhythm constantly propels you forward. The tension between these two aspects gives the piece a superb sense of drama from start to finish.

It doesn’t hurt that this Prelude, more than any other Bach piece I know, constantly develops its themes over the course of the piece. We start out with those appoggiaturas (the grace note in the right hand and the tied-over note in the left):

Which mutate into sequences of harshly chromatic suspensions:

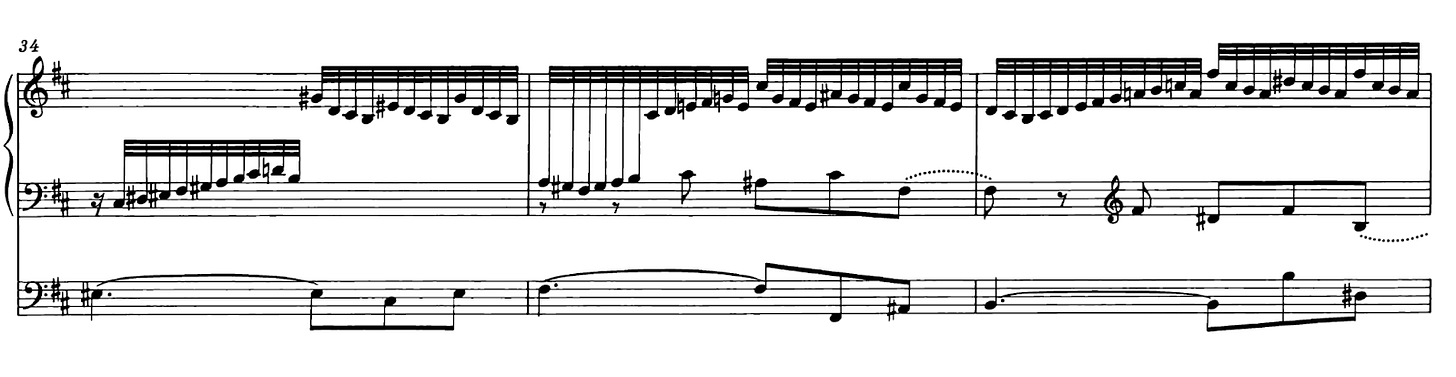

Similarly, those strings of thirty-second notes build themselves up over the course of the piece. Already, you can see hear them start to pile up on the first page:

Before they start to overflow in cascades on subsequent iterations:

Neither of these developmental strategies is unheard-of for Bach, but about halfway through the piece, he takes them both to the next level—at the same time:

These new versions of the thirty-second note cascades and the appoggiaturas (i.e. the sixteenth notes in the last measure here) both imply (local) harmonic changes every eighth note; contrast that with the one-chord-per-bar pace of the example above. So, midway through the piece, Bach has given new versions of his thematic ideas that amp up both the rhythmic and the harmonic excitement. And, to reiterate, the themes do this on top of each other. It’s the kind of thing that Beethoven-minded critics have tried to insist is the pinnacle of compositional technique. I obviously don’t think it’s a problem for Bach that he doesn’t normally fit this mold—but it sure is cool when he does.

The fugue is a complete contrast. Rhythmically homogeneous and harmonically much less intense, it’s based on an almost preposterously simple subject that just outlines a B minor triad:

Later on, he adds another theme that does the same thing, albeit going straight down instead of up and then down:

When juxtaposed with the prelude, it’s hard for this fugue not to sound a little bland. That may even be the point: the counterpoint is pretty sophisticated, so it could be that Bach has pared back the harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic interest to make the listener focus on that. If so, it’s a bold choice, and maybe not 100% musically successful. Or maybe Bach just slapped a fugue he had lying around onto this prelude. It’s hard to know; more on that below.

A Canzona, in case you were wondering, is just an uptempo fugue, typically with repeated notes in the subject. But weirdly, that word “uptempo” doesn’t match how almost anybody plays this piece.2 What gives?

I imagine part of it is the fugue’s countersubject, a descending chromatic fourth:

As musicologists like Ellen Rosand have pointed out, this motive was often associated with laments in the seventeenth century. And Bach used it as such: it’s what he chose for the repeating bassline in the “Crucifixus” from the B-minor Mass. So it’s only natural that people would take this Canzona at a similarly solemn tempo. Except: the “Crucifixus” doesn’t have to go all that slow. (Even Herbert von Karajan understood as much.) We shouldn’t let our preconceptions about “laments” get in the way.

In any case, regardless of tempo, the Canzona is a wonderfully old-fashioned piece, possibly drawing on 70-year-old precedents like Froberger and Frescobaldi, and adopting contrapuntal formulas that I associate with Sweelinck. As an added bonus, it’s two fugues in one: after the first big pause, get ready for a dance-y, triple-time treatment of the same theme.

The last of the Neumeister Chorales (not for us, but in the actual manuscript), “Christ, der du bist” has everything you’d hope for from the young Bach: a succession of nice ideas, each following each other restlessly with a complete lack of formal discipline. Take the opening. First Bach gives a little taste of the tune, then he interrupts himself with a little echo, and only then does he actually start playing the chorale:

Even then, the next phrase will have to wait; there’s a little fughetta to play instead. And after repeating this process with the second phrase, Bach switches things up again. Now the tune’s in the pedals, until the end of the piece.

That’s similar to what goes on, albeit in a much more systematic way, in the BWV 766 Chorale Partitas on “Christ, der du bist.” Since this is the first of the four sets of chorale partitas that we’ll be hearing, a rough outline of the format is in order:

Partita I: Plain hymn setting

Partita II: Two-part variation (bicinium)

Partitas III–VI: variations in faster notes. These also fit pretty standard categories: perpetuum mobile (IV); slow movement with the chorale in the middle (V); jig (VI)

Partita VII: Grand finale, in this case with the tune in the bass/pedals.

It’s possible that the seven partitas correspond in direct ways to the verses of the chorale, although I’m not entirely convinced.

Chorale partitas like BWV 766 are also quite early for Bach. To me, this shows up especially in the realm of harmony. The way he treats this tune often cycles around the same chords, and he often reuses exactly the same figuration when a chord repeats. The result can sometimes feel a bit like being trapped in a washing machine:

It’s extremely cool, and a shame that Bach ironed such things out of his later music.

To close, the other B-minor “free” organ works by Bach. First a Fantasia that’s been inexplicably derided by multiple scholars. (Friedrich Blume tried to prove that it must be by somebody else.) I find this piece pretty charming, so I’m at a loss to explain the hate. It starts out by obsessively exploring one very short motif:

Satisfied after fifteen or so bars, it moves on to a longish coda before giving way to the Imitatio. (Always nice for a Bach piece not to overstay its welcome!) Then comes the Imitatio itself, equally singleminded in its use of one very short theme:

It may not look exactly like a “Prelude and Fugue,” being too miniature on both counts, but there’s nothing wrong with this piece on its own terms. I agree with Peter Williams’ assessment: “charming counterpoint, a genuine sense of melody, and…a striking grasp of harmony.”

But maybe this Fantasia, like the Fugue BWV 544/ii, doesn’t benefit from being played right before the “Corelli” Fugue. Of course, that’s partly my own musical preferences speaking: for a long time, if you’d asked who my favorite composer is, I would have answered with Corelli. (I don’t really have a single answer anymore.) Corelli was probably the first composer to figure out the formulas and patterns that make “common practice tonality” tick, and his music is thus incredibly satisfying without being too predictable. Listen to Amandine Beyer’s Concerti Grossi and Trio Sonnerie’s plush Violin Sonatas if you haven’t already.

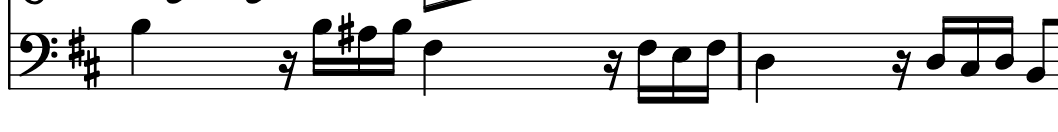

Of course, the BWV 579 fugue isn’t actually by Corelli, but its bones are, and much of the fugue consists of working out the possibilities of Corelli’s theme. It’s a somewhat odd pair of themes, so Bach doesn’t have too many options, but he does manage some neat tricks. Watch how closely the first theme is played in stretto near the end, followed by statements of the countersubject that are literally stacked on top of each other:

And the whole has a nice, “string-y” character that contrasts well with Bach’s typical organ fugues. Those chugging repeated notes are the perfect antidote to the other B-minor fugue.

“Prelude to What?” Part 2

A few months ago, near the beginning of this series, I wrote a long ramble attempting to explain my dissatisfaction with the term “Prelude and Fugue,” and also to clarify what “Prelude” actually means in that context. I stand by it, but there are a couple things that I left out or forgot to include that have been eating at me ever since. Rather than edit them in (yes, I have made edits to old posts in order to correct typos and other slips), I actually think there’s enough there to warrant a sequel. And this week’s pieces are a great opportunity to discuss these issues.

Take, for instance, how I put the B-minor Fantasy together with the “Corelli” fugue. This is a common enough pairing, and it makes some intuitive sense: it’s sort of like matching socks to give an “orphaned” fugued a Fantasy or Prelude to precede it. It makes things fit the more “standard” format.

But what about the Fantasy itself? After all, as this piece used to be so often titled, it’s a “Fantasy and Imitatio”: this piece already has a fugue in it. To get really in the weeds (it’s gonna be one of those weeks), if you look at sources like D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 804, you can find the “Fantasy” part transmitted with no Imitatio. So they must be “separable” and therefore there’s already a “Fantasy and Fugue” element to this piece. Tacking on the Corelli fugue turns it into a “Fantasy and Fugue and Fugue.”

Sort of. It’s not like this is the only Bach Prelude/Fantasy/Toccata written in this format. Is the D-major Prelude and Fugue really more of a “Prelude and Fugue and Fugue”? How about the E-flat-major Prelude from Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I? Would you be surprised to find that fugue or its opening “prelude” circulating separately? Didn’t seem to stop Bach from putting them together.

All that said, I still find it interesting that the Bärenreiter editors decided to simply label BWV 563 “Fantasia,” with no “con imitatio” or “und Imitatio” or similar. It almost seems like they had in mind the “Fantasy and Fugue” pairing with the “Corelli” Fugue. And it also seems like they thought the “Fantasy” would be a bit too slight to constitute its “own piece,” even if sources like P.804 actually show that happening. (Or is it the Imitatio that can’t stand on its own? In the Andreas-Bach-Buch, it at least starts at the top of a fresh page, rather than simply starting at the end of the Fantasy; that’s different from how sources tend to present, for example, the Alla Breve in the D-Major prelude.)

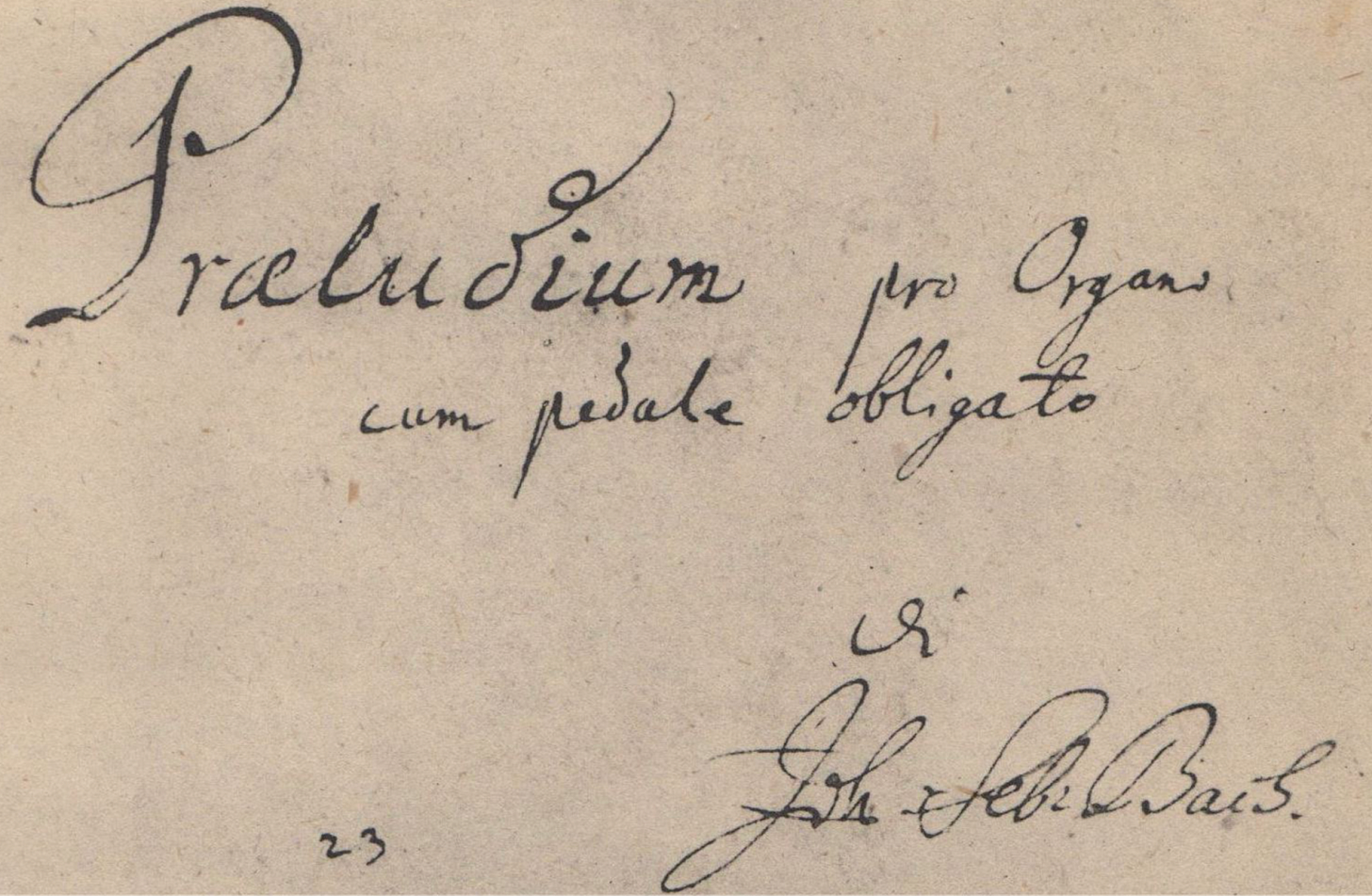

I may be picking apart their logical inconsistencies, but in the end I actually like the Bärnreiter editors’ choice. Even if the Fantasia proper could circulate without its Imitatio, I think it says something that sources that transmit them together still call the piece just “Fantasia.” You can add a Fugue to a Prelude, but the resulting piece will still be “Praeludium”:

That’s Bach’s title page for the B-minor Prelude and Fugue. (Before you ask, the pieces seem to have been copied at the same time.)

This is especially relevant when it concerns pieces that were likely assembled by somebody other than Bach. Yes, there’s some speculation that the C-minor Prelude and Fugue BWV 546 was put together by its copyist. But even if that’s true, they were still liable to call it “Praeludium cum fuga” not “et.”

There’s one extreme case where this may not hold: the “St. Anne” Fugue BWV 552/ii and its prelude BWV 552/i. These two pieces were published as bookends to the Clavierübung III collection, and playing them together is sort of missing the point. But the problem there is less that “the piece” is actually a “Prelude and Fugue” and more that these are two separate pieces, a Prelude and a Fugue.

Still, BWV 552 does link up with some other evidence we have for how Bach structured organ performances. There’s Forkel’s testimony, for instance, that Bach typically began recitals with a Prelude, ended them a Fugue, and played trios etc in between. On the one hand, that matches with the structure of the Clavierübung III perfectly, and is possibly suggestive that more Præludia should in fact be split up and played as bookends. (I think it used to be more fashionable for organists to try this kind of thing.) But on the other hand, Forkel’s account is such a good match for the Clavierübung III that it begins to become suspicious: perhaps his description of an idealized Bach organ recital is actually a description of the published collection. It’s not like he was there, and he certainly wasn’t a perfectly reliable source of other people’s testimony.

Even so, there are smaller-scale matches for Forkel’s description, versions of Preludes and Fugues that survive with trios and similar movements in between. I played one of them a few months ago, and the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue also fits the bill. Except—well, the titles for those pieces in the surviving sources are respectively just “Prelude” and “Toccata.” And they’re definitely not “Simulated Organ Recital” or anything like that.

Of course, I’ll continue to adopt the standard terminology to avoid confusing people; it’s helpful to see on the program that there will be an Imitatio, or an Adagio, or no “second movement.” Just remember: when you put things together like that, it’s all Prelude. No postludes in Bach land.

What I’m Listening To

Sara Glojnarić – Pure Bliss

This is my first encounter with Sara Glojnarić, and it’s a hell of a debut. It’s hard to pin her down with a stylistic label, but there are several clear conceptual through-lines in her work: the detritus of popular culture, an obsession with “secondary parameters” (timbre, density), and technical demands that surpass “virtuosity” and end up somewhere between “athletic challenge” and “sadism.”

Music with such hefty conceptual background can often be dry or sonically disappointing, but Glojnarić has the goods. It probably helps that—to phrase her ideas more crudely—she’s obsessed with compelling and beautiful sounds themselves, and with highwire-level performance demands that provide an instant source of tension and excitement. Better still, she has a pretty great sense of pace, knowing just when to introduce a fresh idea: a great example is the entrance of the electronics two-thirds of the way through Artefacts #2, just when the dialogue between percussion spasms and yelping soprano was starting to get too predictable; a similar effect (brassy electronics again) crops up in the middle of Latitudes. Sometimes (Sugarcoating #4), the overall impression can be almost like Varèse, a combination of pure crystalline stasis in one part, with desperate activity in another to try to shake things loose.

Not everything works: when actual pop songs burst in (Artefacts (2018), especially at the end), it can be just a little too jarring for me. And by the end of the album you pretty much get the idea, although I consistently preferred the newer works, which is a good sign. Pure Bliss is genuinely beautiful (if still pretty restive), and sonically quite a departure from the percussion-heavy music that dominates the rest of the album. Excited to see what Glojnarić comes up with next.

Camille Delaforge with Ensemble Il Caravaggio and Chœur de l’Opéra Royal – Mademoiselle Duval: Les Génies ou les Caractères de l'Amour

Reinoud van Mechelen with A Nocte Temporis and Chœur Chambre de Namur – Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Céphale et Procris

We really are living in the golden age of obscure opera recordings. Here we have a second recording of Jacquet’s Céphale and what I think is the premiere recording of Duval’s Les Génies: the first two operas by women performed at the Paris Opera. The singing, playing, and recording quality on both is excellent.

I have to say that it’s a bit hard for me to judge music in this style, dominated as it is by text-oriented conventions and dramatic formulas. That’s especially true for the Lullian opera of Jacquet’s time: the tunes are quite nice, and the instrumental dances can be a lot of fun—try not to tap your toes to “Les démons”—and yet the music can get pretty samey. (The choruses the demons actually sing have a lot less character than the instrumental, although the string writing does liven up their second one.) But that’s not to say that Jacquet is completely bound to convention: the genuinely tragic, somber ending is a big departure from anything Lully would have done. No closing ballet, no closing chorus; fade to black.

On the whole, though, I find the 1730s style of Mlle. Duval a lot easier to like. (Just as Campra and Rameau are much easier for me than Lully.) The bigger role of the chorus and orchestra certainly helps, as does the increased use of textural and tempo change-ups to carry the drama forward: some of the opening numbers are getting pretty close to the pacing of later Gluck, an operatic sweet spot for me. And there are fun and exciting moments throughout: the whole fifth scene of Entrée III crackles along. Even if the dramatic beats of the opera3 are probably more conventional than in Jacquet’s (there’s our rousing final chorus), it’s still quite an enjoyable listen. Shame we don’t even know the composer’s first name.

Brittany Howard – What Now

I put this in my listening queue and forgot about it; it came on after a new album of song cycles by Charles Villiers Stanford (meh) and I had no idea what it was. By the time the title track came on, I had to look up who it was. Imagine my surprise.

I wasn’t hip to Alabama Shakes in 2019, so my introduction to Brittany Howard was Jaime. That album, more or less, picks up from where the band left off: if Alabama Shakes is sort of like a Stax records version of garage rock (ever wanted to hear a soul take on shoegaze?), Howard’s solo debut continued in a similarly historicist vein, with its most played track being confusable for nostalgic Americana kitsch.

Maybe Howard wanted to blow that impression away this time. There were electronics-based songs on Jaime too, but nothing like the grooves and sounds we get here; “Prove It to You” is literally just house music. There are still great rockers (“Power to Undo”), neo-soul jams (“I Don’t”), and atmospheric R&B (“Samson”); but there’s a lot more atmospheric playing on singing bowls (opening track and at the ends of the others), experimental psychedelic grooving (“Red Flags”) and other delightful sonic. “Experiment” and “evolution” aren’t necessarily good for their own sake, but it’s hard not to be impressed when the results are as good as this. I’m sure she’ll take me by surprise next time too.

IU – “Holssi [Dandelion Spore]”

IU’s story is, if nothing else, one of consistently great musical collaborations. That’s most visible in her knack for getting guest appearances from artists at the peak of their fame: GAIN and Jonghyun in 2013; G-Dragon in 2017; Suga in 2020; V and (soon) Hyein in 2024 (in a music video featuring Tang Wei). But it’s also a story about recruiting a talented and ever-shifting cast of songwriters and producers. The trend really kicked off with Last Fantasy, which was billed as a collection of songs from some of Korea’s most established pop (both traditional and K-) songwriters, along with an appearance from IU’s beloved Corinne Bailey Rae. And it’s continued down to the present: for 2021’s LILAC, that entailed bringing in R&B star Naul, pop songwriter extraordinaire Ryan Jhun, AKMU’s quirky, indie pop-adjacent Lee Chanhyuk, and notoriously reclusive singer DEAN for a reggae-inflected alt-R&B track.

As that litany shows, bringing in such a variety of songwriters is a way to ensure a consistently diverse array of sounds and generic influences. Of course, generic flexibility is maybe IU’s single biggest musical hallmark—there aren’t many musicians who would sandwich the jazz/bossa/samba-revival album Modern Times between synthpop releases “Sea of Moonlight” and “Sogyeokdong.” (Those songs, too, are collaborations.) But it’s also dangerous; mashing all those sounds together obviously risks sonic incoherence. Thus, it’s pretty impressive that LILAC and Last Fantasy each manage to have such a cohesive sound while letting their songs have such distinct musical identities. Really, I’ve probably understated things: beyond the songs listed above, LILAC also tries on city pop, Broadway, and even rap. So what’s impressive is frankly just that the album doesn’t completely fall apart at the seams.

Needless to say, it’s a lot of work to pull such disparate strands together. And it’s a lot of work to keep working with new people, and to keep trying out new styles. Already in 2016, IU was complaining that fans expected her to constantly change things up: “I’m not some kind of Pokémon; I can’t evolve every year.” So, to counterbalance all these musical visitors, IU has also maintained close collaborations with a handful of musicians. Lee Jong-hoon has written and produced songs for her since her debut; Lee Min-soo, composer of “Good Day,” came back for “YOU&I,” “The Red Shoes,” and “Above the Time” over a span of 10 years; and Kim Je-hwi, who debuted as arranger of “Glasses” in 2015, then came back to write the smash hit “Through the Night,” the much better “dlwlrma” (both 2017), and so on through 2021’s “My Sea.” Strong as IU’s lyrics and songwriting can be, an enormous part of the credit for her musical success must go to these composers.4 She knows it; that’s why she keeps working with them.

It’s no coincidence that the names of these trusted collaborators dominate the credits for IU’s most personal releases (and consistent fan favorites) Chat-Shire and Love Poem. And on those two albums in particular, the list of “close collaborators” should also include Lee Chae-kyu. To be sure, he’s been a less consistent musical associate; but he’s responsible for two of IU’s biggest hits, and was entrusted with fairly sensitively autobiographical lyrics. Maybe more importantly, “Blueming” and “Twenty-Three” both have sounds fairly distinct from the rest of IU’s discography. I’ve missed hearing his work.

Now Chae-kyu’s back.5 The connection with Chat-Shire is probably not a coincidence; IU basically said as much, and speculation that the upcoming album The Winning (yes, that’s the title) might be linked to Chat-Shire has been rampant ever since IU made it clear that the album would be about turning thirty-two. Reverse “Twenty-Three”?

Not really, or at least not yet. But “Holssi” definitely includes callbacks to other moments in IU’s discography, including Chae-kyu’s songs. So it has the one-chord verses of “Red Queen” and the sarcastic question-echoes of the last chorus from “Twenty-Three.” The beat has some of the same grimy, thudding undertow of “Black Out” (Lee Jonghoon is credited on both songs); the instrumentation is pared back à la “BBIBBI”; the airy vocal harmonies from the bridge of “Flu” have returned; so has the sing-talk of “Sleepless Rainy Night,” or, if you want to call this rapping, the verse from “Coin.” For listeners who know these songs, “Holssi” has a clear retrospective flavor.

It also sounds like a complete departure; IU may not be a Pokémon, but she’s definitely evolved again. Even “BBIBBI” and “Red Queen” aren’t this stripped-back in terms of harmony and melody: basically the entire song consists of blues-scale riffing over a single C7 chord. No other IU song leans nearly this far into hip-hop production styles. Really, between the harmonies and the sonics, the song sounds almost more like NMIXX’s “DASH” than anything by IU to date. Or, when she ends with “God be with ya,” you have to wonder if she has in mind her beloved g.o.d.

She also probably has the present musical environment in mind as well. (“DASH” did do quite well on music shows.) “Minimalist” production is in, and the Tweety bird collaboration, although with longstanding roots, seems to me pretty clearly to be a response to NewJeans x Powerpuff Girls. (As if actually featuring Hyein on the album weren’t enough.) The choreography in the video seems destined for Tiktok dance challenges. And shooting the video in L.A. is probably at least partially meant to draw in U.S. audiences in advance of her first world tour.

All of that sounds pretty cynical, and it also sounds like the kind of music I really don’t like: I don’t normally go for songs with neither much of a chord progression nor a distinctive melody. So I’m a bit shocked that I do actually like “Holssi”—infinitely more, for example, than the roughly comparable “BBIBBI,” which I find pretty boring despite the lyrics and video. What’s working here, musically? (No comment on the video.)

Well, like other successful one-chord songs from Junior Walker to æspa, “Holssi” both luxuriates in the melodic possibilities of its single harmony, and also knows to keep changing things up. NewJeans-level repetitiousness would be a death sentence in a song like this. So, for instance, the use of register is plotted extremely carefully. The verses stay low, around middle C; the prechorus jumps up almost an octave; the chorus then repeats this trajectory with a slow climb up; and the postchorus stays up in the clouds (around E5). Similarly, the amount of vocal layering and effects steadily increase: a fairly close-miked sound in the verses, airier double-tracking and occasional harmony in the prechorus, multiple vocal parts in the chorus, and sustained harmony in the postchorus. Giving the “zones” of the song these identifiable characteristics helps keep things fresh even as very little else changes.

Actually, even less changes between the sections of the song than you might expect. To me, the beginning of the chorus pretty clearly recalls the beginning of the verse. And, cleverly, the postchorus is first introduced as a background harmony to the chorus itself (around 2:28): that is, the postchorus is basically just the ending of the chorus with the tune pushed back in the mix and the backing vocals bumped up. It should sound repetitious but it isn’t.

And the advantage of keeping the music so relentlessly fixated on one chord is that it really makes things pop when there’s a harmonic change. So the prechorus’s already-juicy chord progression (♭VI-IV-♭VII-I the second time around) sounds especially lush in context.

Then there’s the production itself. Just like in “Black Out,” the beat really makes this song work. But beyond that, the constantly shifting series of vocal effects (echoes, stutters, etc.) and backing instruments (little synth interjections that come in and out; the drum machine late in the second verse; the beefed-up drums in the postchorus) keep things interesting throughout.

It wouldn’t be the first time the production has saved an IU song. It’s vaguely blasphemous to say so, but “Palette” isn’t much of a song by itself; it’s almost as musically static as “Holssi,” albeit with a (bland) tune in the chorus. Still, the instrumentals make it a very hard song for me to skip: the constant introduction of cool sounds (synth blips, different electric keyboards, tablas) are enough to take me through to G-Dragon’s verse.

Lee Jong-hoon, of course, produced “Palette” as well as “Holssi.” Even on songs she wrote, collaboration is a big part of what makes IU IU.

Also liked…

Lao – Chapultepec

Declan McKenna – What Happened to the Beach?

Rolf Schulte and Ursula Oppens – American Violin Music: 1947–2000

Eliades Ochoa – Guajiro

Northern Resonance – Vision of Three

DJ Harrison – Shades of Yesterday

Helado Negro – Phasor

What I’m Reading

I’m not sure there’s another book like T. Sankaran and Matthew Allen (and Daniel Neuman)’s The Life of Music in South India. Here’s the barebones story: Neuman’s 1980 book The Life of Music in North India inspired Sankaran, then already 74, to try his hand at a comparable book for South India—or at least a text with a comparable title. Allen, a mentee of Sankaran, saw the draft and conducted interviews in the mid-‘80s to try to flesh out the somewhat telegraphic typescript. And now, forty years later, Sankaran’s draft, the passages of Neuman that inspired it, and Allen’s interviews are all published here, alongside a bevy of introductions, prefaces, footnotes, and other tools for understanding what the heck is going on.

If that sounds like a confused mess of a text—well, that’s pretty much what it is. It’s not exactly user-friendly, and completely non-organized; I’d recommend starting with the introductions and then skipping to Chapter 4 before coming back around at the end. (If you have no background in Carnatic music, Allen’s short book with T. Viswanathan has everything you need to at least know what’s going on here.) To the extent that Neuman’s book attempted to be systematic, Sankaran’s does not really follow its model. Treat it more as some combination of oral history and autobiographical testimony.

Still, that testimony attempts and contains some pretty interesting stuff. Not least, Sankaran (indirectly, and then amplified by the editors) attempts direct comparisons between Hindustani and Carnatic music, something I always want to see more of but which is rarely the focus of ethnomusicological writing on South Asian music. Sankaran’s remarks on the differing social settings of music-making in each tradition (temples in the South vs. private performances for connoisseurs in the North) are illuminating, and he follows them up with a nice amount of detail about the social situation of temple musicians (including, before 1947, devadasis).

There’s also valuable and fascinating information that really gets into the weeds of early twentieth-century Carnatic performance styles. The discussion of different schools of mridangam playing in Chapter 5 is a very cool read, and there are boatloads of biographical tidbits about various musicians throughout the book.

Even Sankaran’s ax-grinding does reveal some genuinely interesting facts (even in the form of data from concert programs in the appendix) and patterns concerning various kinds of hierarchies in Carnatic music: gender bias, caste bias, linguistic bias, bias toward soloists, etc. So, for instance, I learned a great deal about the evolution of attitudes toward Telugu and Tamil in the early twentieth century, as coupled with the revival, and recontextualization of Tyagaraja’s works. (For that matter, I hadn’t even been aware that Tyagaraja’s status at the pinnacle of the canon is quite such a recent development.)

It’s probably ungracious to wish more work on editors who already put so much into a book, but I still would have loved more detail in the paratexts about what’s changed since 1986. To be sure, they’re careful to frame this book as a historical document, its info already dated when it was written. And probably an account of those changes would be another monograph in itself (although this one is pretty slim). But it would be good to know quite how many of the prejudices and restrictions Sankaran discusses have been left in the past.

In any case, there’s a lot to this book, and given its lack of rigid structure, it’s a fun one to dip in and out of. Now to finally go through Neuman’s original book too…

A few others:

VAN Magazine – The Price is Wrong

Rest of World – How Showmax, an African streaming service, dethroned Netflix

Common Edge – Havana’s Evolving Public-Private Landscape

Nature – Absence of female partners can explain the dawn chorus of birds

Hyperallergic – The Private Life of Paño Arte

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

Except for when the Feast of the Annunciation happens to land in the right spot.

As usual, bless Benjamin Alard for going against the trend.

Opéra-Ballet, to be fair, which is a slightly different genre from Céphale.

He also worked on IU’s last single, “Strawberry Moon,” to more mixed results.

Glojnaric Sugar Coating #4 is great! Like listening to the Carter Concerto for Orchestra as played by the Chicago Art Ensemble, AACM, and friends...