Week 15: 5 February 2024 – "9/8" Prelude and Candlemas

Plus: articulation heresies, VANNER hits the JACKPOT, Rickey Henderson's legacy, and more!

Hello from Madison! I’m excited to be visiting here throughout the semester to teach harpsichord/continuo and coach UW’s collegium.

UW now acknowledges that its foundation went in tandem with the dispossession of the Ho-Chunk people, and it’s taking some steps to “to deeply consider our shared past and present with Indigenous peoples in this place.” Would that UChicago had even that level of initiative. (With the caveat that UW had better mean it when they say “it is a first step”; it’s worrying to see their “media coverage” page trail off after 2022.)

Maybe a bit sadly for an undertaking with the “people of the big voice,” it doesn’t seem like “Our Shared Future” has featured music in a super prominent way. And it’s a little hard to find recordings of Ho-Chunk musical activity in Madison today. But that may change: I did turn up this lovely article about the archiving and preservation efforts of Madison-based Ho-Chunk musician Clint Greendeer (hear one recent song by him here), including his father’s music (of which there are otherwise just a few Youtube clips). If they’re interested in sharing those recordings more broadly, I hope they get the funding and support to circulate them.

Week 15: 5 February 2024 – “9/8“ Prelude and Candlemas

Please save applause for the end of each set

Concerto in G, BWV 592 (after Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar)

i. [Allegro]

ii. Grave

iii. Presto

Fantasia and Fugue in A minor, BWV 561

Alla breve in D, BWV 589

Mit Fried’ und Freud’ich fahr dahin, BWV 616

Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf, BWV 617

Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf, BWV 1092

Fugue in C minor, BWV 575

Prelude and Fugue “9/8” in C, BWV 547

Having only just met Prince Johann Ernst, it’s time to say goodbye with this G-major concerto. And in fact, even though we’re only at the midpoint of this series (gulp!), we’re getting pretty close to the end of Bach’s concerto arrangements: partly due to what I thought it might be appropriate to program during Lent (no “chamber” or “orchestral” music), and partly due to inattentiveness on my part, there’s only one more to go (Vivaldi’s “Gran Mogul”), in April. Savor the Italian flavor while you can.

I’ve struggled to put into words how I feel about this piece. I had a little more to say about Johann Ernst’s C-major concerto movement, not least because at that point in the series, I hadn’t yet devoted about dozen posts to extolling the virtues of Vivaldian harmonic rhythm. But whereas that piece is pretty successful Fauxvaldi, I think this one is something more. (Maybe that’s why Bach arranged all three movements this time.) I think the Netherlands Bach Society does a good job here:

It is a piece to be reckoned with. The first movement exudes such overwhelming joy that it brings tears to your eyes. The simple little motifs of the solo and tutti parts are played on various keyboards always a step higher, until they reach the highest regions. It is one-dimensional in the very best sense of the word. As a contemplative counterpart, the middle movement is dominated by a rather mysterious, legato rhythm. In the final movement, the same overwhelming youthful exuberance returns again.

I can only guess what precisely “one-dimensional in the very best sense of the word” is supposed to mean, but it does get at the unceasing buoyancy of the first movement’s rhythms.

I also don’t really know what a “legato rhythm” is. But in any case, the slow movement is, paradoxically, probably a lot less likely to “bring tears to your eyes” than the upbeat first—Johann Ernst didn’t quite figure out Vivaldi’s long melodies, instead substituting a somber but somewhat formulaic Sarabande. (The dotted-rhythm unison passages that frame the movement are, however, clearly Vivaldi-inspired.) Fortunately, the last movement gets back to what Johann Ernst does best. When played at a suitably zippy presto, the finale absolutely combusts when its opening scrubbing gives way to a fusillade of thirty-second notes. It’s high-octane and somewhat breathless stuff: remember that the composer was at most eighteen when this piece was written.

Really, the best endorsement I have for this piece is that Bach arranged it twice, producing a manuals-only harpsichord version as well as this pedaliter one.1 Like the Johannes-Passion or last week’s Trio, such tinkering and revising is a definite sign that Bach was repeatedly paying attention to this music. You should too.

I’m going to go out on a limb and assert that BWV 561 is the best of the Bach organ works whose attribution is in doubt. Yes, I’m including Toccata and Fugue in D Minor on that list. Hear me out.

Let me back up first and try to explain why this piece’s authorship is in question to begin with. It goes without saying that there’s no manuscript in Bach’s hand, nor indeed any source from within a couple decades of his lifetime; the ascription to “Giovanni Sebastiano Bach” comes much later. And the piece’s style doesn’t really fit anything else we know by Bach: the opening, with its burbling thirty-second notes, sounds a whole lot like Pachelbel and not very much like the composer of the “Great” G-minor.

Still, we know that the composer of the “Great” G-minor was also big into Pachelbel, and spent much of his early years copying and emulating older music. Besides, this “unusual” figuration is awfully close to Bach’s writing in pieces like the B-flat-major Prelude from Book 1 of the Well-Tempered Clavier. To be fair, scholars have also wondered if this is “really” a harpsichord piece as well. (The pedal part is entirely playable with your hands, if you want to.)

The other main reason this Fantasy gets excluded from the canon—it wasn’t included in the Bärenreiter edition of Bach’s organ works until the most recent update—is the Fugue in the middle. Similarly to the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, scholars have often turned up their nose at this fugue, calling it simplistic in its sparseness and directness.

I’ve already expressed my dissatisfaction with this general line of argument—“it’s not ‘genius’ so it can’t be Bach”—but I find especially unfortunate here. Simplicity is the reason to like this fugue, not to dismiss it: it’s utterly charming in a way that Bach’s later, more “sophisticated” fugues could never be. (Not that they lack for charms, just different ones.) Star Wars fans and anybody who’s listened to Reger knows that “denser” is not necessarily better. Maybe this piece isn’t by Bach, but it’s such a nice change of pace to include it. Bravo to whoever wrote it.

Speaking of dense, contrapuntally sophisticated fugues: sort of along the lines of “Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir,” the Alla breve is something like a test of why you listen to Bach. After all, this piece is 100% pure fugue—and double fugue at that, with the two subjects immediately swapping places in the texture (“invertible counterpoint” at a variety of intervals). Moreover, the piece has “modern” street cred by virtue of its rather adventurous harmonies: unusual modulations start cropping up on the first page and things really go to hell near the end, when the pedals start descending chromatically and it becomes hard to figure out what you would even call the chords.

But despite all that, this is not exactly a well-loved or much-played piece. Sure, it doesn’t help that it’s a fugue with no prelude, but I think the larger culprit is the writing itself: this is one of Bach’s dryest organ pieces, dispensing with rhythmic contrast or any of his more satisfying Italianate harmonic formula. If you like it, you really do like plain counterpoint; if you don’t love it, no harm no foul—there’s much more to Bach’s organ pieces than that.

Today isn’t just Groundhog Day: it’s also Candlemas. (Not a coincidence.) And in Bach’s Germany, that meant the Feast of the Purification, i.e. the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple.

If you remember anything from that part of Luke, you might recall that it’s the origin of the Song of Simeon, the Nunc dimittis that’s sung after the Magnificat. “Now you dismiss your servant” is the Catholic version; unsurprising that Luther would substitute “In peace and joy I now depart” (“Mit Fried und Freud…”). And Bach seems to have gone even farther in the same direction, absolutely loading this chorale with the quick dactylic (“long, short-short”) rhythm he so often used in festive music. Don’t let the minor key confuse you: this is joyous music. (No comment about “peace.”)

Simeon’s story doesn’t quite end with those words though. “Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf” gives Simeon’s final words, with more of an emphasis on “peace,” and less on “joy.” I’m still not sure Bach got the memo. The Orgelbüchlein prelude on this tune (BWV 617) is as busy as Bach gets: using the ultra-fast time signature of 24/16, he writes a sewing machine-like string of never-ending sixteenth notes for the left hand, full of huge and awkward leaps that complement the nervously jumpy pedal part. Maybe the tune, given in slow notes in the right hand, is supposed to come across as a “peaceful” contrast. Or maybe the quick notes represent a restlessness to “enter the next world” already. We can’t forget that Bach’s attitude toward death was much more, let’s say, “religiously extreme” than most of ours.

Then there’s the Neumeister Chorale setting of this tune. As usual, the earlier piece is much less steadyhanded and sophisticated than the Orgelbüchlein chorale, but also delightful for its lack of discipline. This piece can never quite decide what it wants to be. Sometimes you get a straightforward harmonization of the hymn. Other times, the hymn is broken up into little fragments with echos. Still other times, it’s accompanied, Orgelbüchlein-style by running figures in the lower voices. Each of these textures comes and goes more or less at random. It’s certainly hard to be bored listening to this piece.

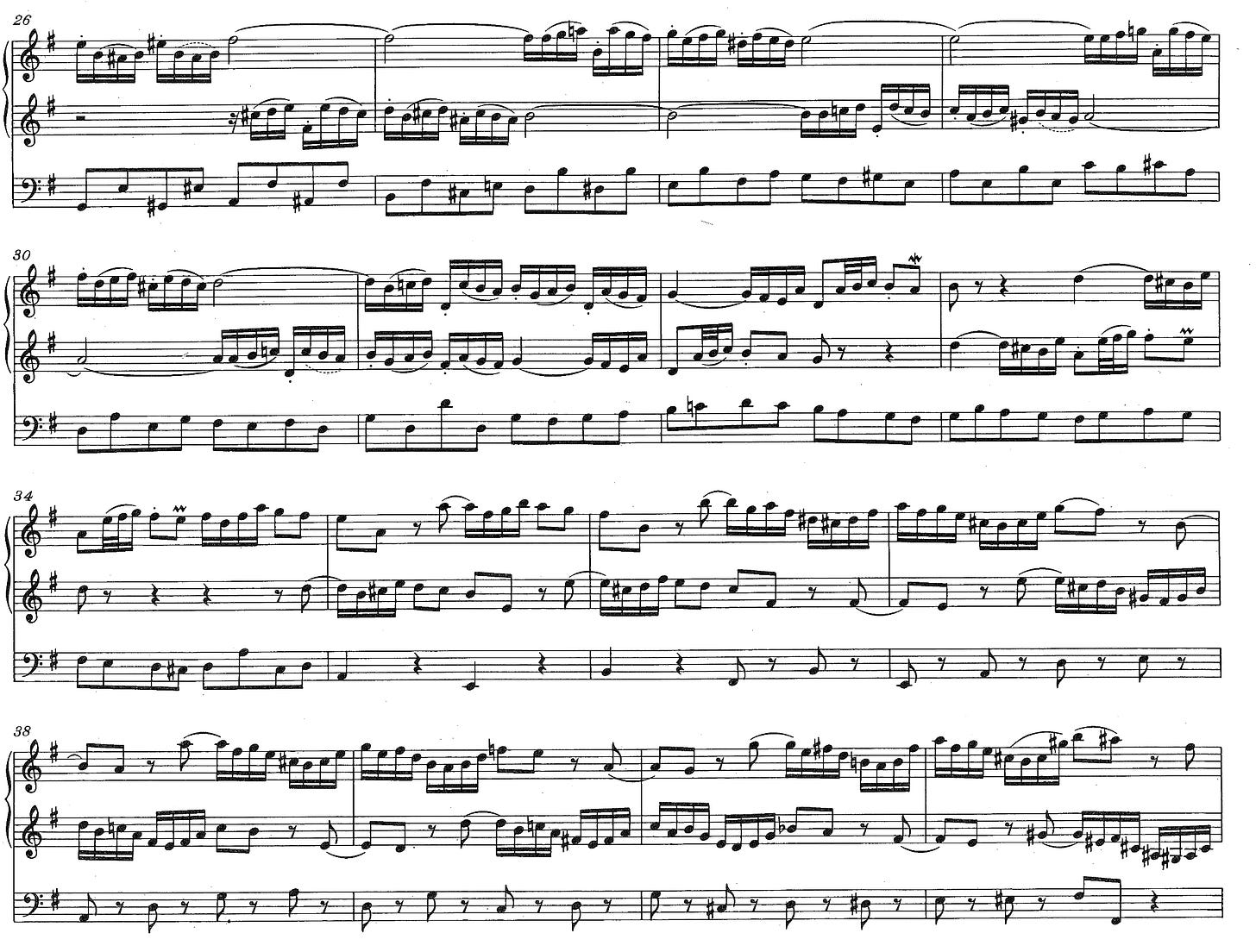

If an organ fugue subject is like a promise or a threat, then the C-minor fugue BWV 575 and the C-major fugue BWV 547/ii are Bach’s biggest welchers. Both of them start with fugue subjects that hint at future pyrotechnics in the pedals—“how are you supposed to play that with your feet?”—and proceed to evade the difficulties entirely.

To see why, let’s take them one at a time. The C-minor fugue begins with this subject:

Thinking in terms of your two feet, you can start to see the problem: the opening measure especially would entail a lot of awkward crossing in front and behind to be played in the pedals. Bach wasn’t above such virtuoso maneuvers, but not usually at this scale; and in the harmonic “neighbors” of this key, the difficulty could get out of hand pretty fast.

Bach’s solution is simply to never have the feet enter at all. At least for the “fugue proper: when they do come in, it’s for a concluding part that breaks from the music of the fugue entirely.2 Or almost entirely: listen for one last reminiscence of the fugue subject in the very final measure. But not in the pedals.

The C-major Fugue takes a slightly different tack. To be sure, it also keeps you waiting a good while for the pedals:

(Please excuse the squeaks and messiness; I was mostly trying to figure out the registrations and page turns.)

But you might notice that once the pedal comes in (2/3 of the way through the piece!), it does actually have the tune—just twice as slow. The hands never actually get to play the slowed-down version of the theme either: even though the pedal participates more fully in this fugue, it still exists in something like its own world. The result sounds almost like somebody added a new pedal part to a piece from the Well-Tempered Clavier; it’s certainly a unique way to write an organ fugue.

The pedal exists in its own world in the prelude too, mostly playing a falling, carillon-like ostinato pattern while the hands constantly rev their engines going higher and higher. As the nickname indicates, this prelude is in 9/8, three times three, a jig that’s even more dance-y than usual. A lot of organists like to play this piece around Christmas and I understand why: there aren’t many Bach organ pieces that sound this relentlessly festive. It’s a good piece to clear off the books as we round out Epiphanytide and head toward Lent.

How much is it OK to add? Part II: Articulation

The eagle-eared among you, especially organists, may have noticed something slightly odd about how I play the opening of the C-major fugue. Here it is notated:

As usual with Baroque keyboard music, there’s no indication of articulation, e.g. which notes to play slurred and which to play detached. But you can hear that I like to play a fairly strong slur across three of the eighth notes in the theme:

This articulation does a few things. It helps bring out the shape of the theme, which in turn gives the rhythm a little juice: separating out the last eighth of the group gives it more oomph as an upbeat. These slurs also help give the theme a distinctive sound, which is important in a fugue as dense as this one, where the (relatively nondescript) subject is constantly being covered up by webs of sixteenths, entrances in other voices, and other confounds. I’m not being 100% consistent in applying this articulation scheme (there’s no “rule” anywhere saying a fugue subject always has to sound the same), but I think it helps the piece in a few ways.

That’s a tiny bit of a heretical position with respect to organ orthodoxy by now. The (derogatory) phrase I learned for this kind of slurring is “applied articulation,” with the implication that the articulation is sort of haphazardly painted on by the performer, disrespecting the underlying music.

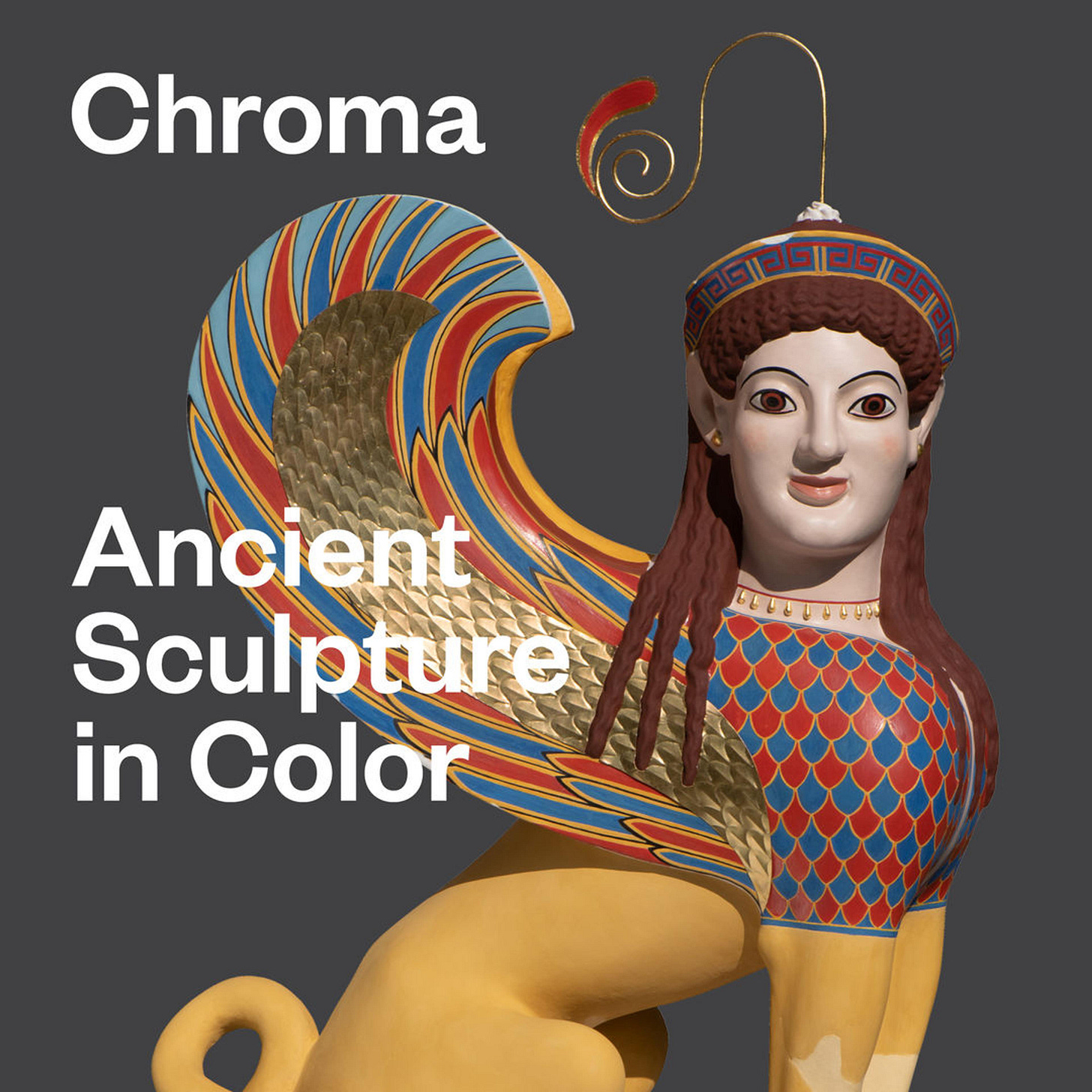

Now, some people definitely did used to do exactly that. Let me reach for an analogy here—one that I’ve already foreshadowed. You’re probably all aware by now that Greek and Roman marble sculptures were very often (typically?) painted in color, often with fairly bright pigments. In the decades since this discovery, there have been waves of shows offering purported reconstructions of the original colorations. Here’s the poster for a recent one at the Met:

Naturally, the press around these shows tends to emphasize how “gaudy” the sculptures now look, even “tacky” or “tasteless.”

And tasteless they are; although there is indeed oodles of evidence for these sculptures being painted, the reconstructions are based on little more than that bare fact and knowledge of which pigments were used. That’s because there’s basically no surviving evidence for how they were used. They don’t know much about the binders, for instance, or other mitigating factors that may have dulled the colors. They don’t know how thickly or consistently they were applied. And they don’t know how or if they were supposed to fade over time. You get the idea. It’s “applied coloration,” designed to make a point and draw attention to itself.

Still, it only makes sense to provide some shock value if you want to reshape how people view Classical art. The basic point (that these statues were painted) is still true, and the connection they seek to disrupt—between the fetishization of “pure white marble” and the desire for a “pure White antiquity”—is definitely real. Some coloration is a good idea; the only question is how much.

OK, hopefully my analogy is reasonably clear. If we decide to keep the present, paint-free state of Ancient statuary as our image of its original form, that’s not avoiding the choice of how to color them: it’s effectively coloring them white. Similarly, there’s no such thing as an “absence of articulation” in music. Not applying articulations is, in fact, applying articulation (usually detaching every note)—it’s just a matter of what you think is tasteful and motivated.

Basically every organist would agree that some gradations of short and long are necessary to convey strong and weak beats and indicate phrasing. And I think most would also agree that articulation can and should indicate groupings. In the second system (mm.5–6) of this excerpt (from Trio Sonata No.1), the right hand has visually obvious groups of “3+1,” and it makes sense to make that audible in some fashion:

But not everybody would go so far as to actually slur them. I think that’s too conservative. There are no slurs written in the fast movements of this sonata, but Sonata No.6 is full of them in comparable passages:

Call it “application by analogy.” I don’t think that slurs are a quirk of Sonata No.6, but rather something that Bach didn’t feel the need to indicate for Sonata No.1. We should apply them wherever it seems like Sonata No.6 would use them.

So that would be Articulation Heresy #1: reclaiming “applied articulation” by adding slurs—not willy-nilly, but more often than is generally regarded as OK. Hopefully the result doesn’t sound like an overly-polychromed-up Ancient sculpture.

Since I’m spouting articulation heresies, I might as well broach another. A classic “rule” of Baroque keyboard technique is “don’t slur over the barline”—it weakens the downbeat and is very very rarely indicated until around the time of Mozart. More than fair, but I still think there are some situations where it’s motivated. Take “vocal-style” music, like “Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit” BWV 669 (you’ll have to wait until the end of the series for this one):

The first three notes correspond to “Ky-ri-e,” and would certainly not be sung with an articulation between the “ri” and “e.” No problem at first, but the second entrance (in the top voice) is across a barline. I’d rather break the rule than break the word. And I suspect that, even without words to guide us, a decent number of Bach’s “choral-style” fugues benefit from the same treatement. You may have even heard me do it before…

What I’m Listening To

Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques – Louise Bertin: Fausto

I can’t believe there’s a recording of this piece now. I didn’t even know that there was even a surviving orchestral score (apparently only rediscovered recently).

I first found out about Bertin as part of, let’s call it, the “Berlioz extended universe.” (He originally dedicated one of my all-time favorite pieces to her and wrote a decent amount about her in the Mémoires.) And once you start learning things about Bertin, it’s a little hard to believe she hasn’t gotten more attention. A poet herself, her literary taste was impeccable: a first opera based on Sir Walter Scott,3 then one of the very first operas based on Goethe’s Faust,4 with her own libretto (!) in Italian (??). And to cap it off, she got Victor Hugo interested enough to collaborate on a Notre-Dame de Paris opera (Esmerelda), with a vocal score edited by Franz Liszt.

The music’s intriguing too. Bertin obviously had many of the same influences as Berlioz—Spontini and Weber are the most audible to me—but without the classicizing pull of Gluck. That makes for music that can sound pretty wild, in both its orchestration choices and its frequent change-ups of melody, texture, and tempo. There are relatively few “big tunes,” which may not be a plus for opera-lovers; but that honestly helps move the action forward for me.

The real miracle of this recording is that it’s an excellent performance; the Bru Zane project has recruited really top-shelf ensembles and singers for these obscure operas. Part of that has involved stretching ensembles like Les Talens Lyriques beyond their normal stomping grounds (Lully and Rameau). They perform admirably, but there’s still some occasional raggedness. (Not nearly as much as you would have heard in 1831.) Meanwhile the singing, led by name-brands like Karina Gauvin, is fabulous. Even if “influenced by Spontini and friends with Berlioz” doesn’t sound like your cup of tea, it’s still worth trying out. At the very least, there’s a lot to learn from this opera.

Ndox Electrique – Tëd ak Mame Coumba Lamba ak Mame Coumba Mbang

If you know the music of Ifriqiyya Electrique, you might have flashbacks listening to this; I think this is something like a better version of the same thing. Here’s a recipe. Take N’doëp ritual chants and drumming. Put heavy distortion on the voices and reverb the hell out of the drums until it sounds punchy and massive. Then turn up the fuzz on your guitars until you get laserbeams. Sometimes you play fairly recognizable riffs and grooves (“He Yay Naliné”). Otherwise, you play drone-y stuff verging on sunn O))) (“Sango Mara Riré”). The result is kind of insane and I totally love it.

Peso Pluma and Anitta – “Bellakeo”

Fuerza Regida x Marshmello – “HARLEY QUINN”

And who asked for a Peso Pluma synthpop song? Even if the result is pretty good by itself (and certainly very creative), I don’t think this is exactly using him to optimum effect.

Look, so I didn’t know this song yet when I wrote that; I must have been missing it at the end of the Hot 100, which it’s been climbing since December. Anyway, “Bellakeo” isn’t “Synthpop” in the same way as the Kali Uchis song; it’s more like synthed up reggaeton.

Still, any Peso Pluma moves outside of corrido-land is still worth watching. To my mind, there wasn’t a single US pop music trend more important last year than the ascent of “regional Mexican music” to Hot 100-levels of mainstream popularity; all of a sudden, last Spring, you could count on 10% or more of the chart being in Spanish—or even eleven songs by Peso Pluma alone.

I think one of the factors enabling this music’s rise was that, once the style as a whole broke through, any song with sufficiently engaging lyrics (e.g. Fuerza Regida’s “Sabor Fresa”) could easily appeal to existing audiences, because the songs all sounded kind of the same. Having already complained about that musical monotony here, I won’t belabor the point, but I will register my appreciation for Peso Pluma mixing things up.

Likewise for Fuerza Regida. This song is old news by now, but I think part of what’s helped it stay on the charts is its distinctive sound. Sure, Marshmello’s beats aren’t blowing anybody’s mind, but they add just enough juice to these norteños to make them pop. As “Regional Mexican” continues to take over the mainstream, I look forward to more of these experiments and crossings-over.

VANNER – CAPTURE THE FLAG

I’ll admit it: I barely know anything about Vanner (I think they were on some reality show?), but—with apologies to (G)I-DLE—this was easily my favorite K-pop release of the week. “Jackpot” might have kind of cheesy lyrics, but it rocks surprisingly hard. For once, the song combines memorable tunes (the beginning of the chorus has two of them at once, even), an infectious and intriguingly-scored beat (those handclaps), ear-catching instrumentals (that ever-shifting guitar sound), and a variety of singing styles and ranges: unlike in so many songs, the high notes and shouting both make perfect sense in context. I also like how the song’s repetition of key phrases helps things hang together: the “Jack to the pot” hook (I don’t know what it means either) ties the first verse into the pre-chorus, and then morphs into the post-chorus hook. No part of the song drags: verses that have a relentless drive to them, no empty chorus, and a bridge that ups the ante. Uptempo, maximalist music: good, old-fashioned K-pop. The other ALLCAPS tracks on the album are pretty good too, in similar ways. Groovy stuff!

I’ve noticed that this kind of high-energy sound is much more likely to come from boy groups recently. To paint with too broad a brush, that’s something of a reversal from years past. Even five years ago, you might expect a certain number of “boring paint-by-numbers R&B” or “slightly dreary pop-rock” singles from boy groups, while girl groups would be more likely to go all-out with cutesy, sexy, “girl crush,” or other similarly high-energy concepts. Obviously that’s far too strong of a generalization on both sides (yes, I’ve listened to both The Velvet and Love&Letter); the point is just that, if a single didn’t go anywhere or lacked enough “punch,” it was probably more likely to come from a boy group.

That reversed a couple years ago, in a way that’s particularly noticeable with girl groups under HYBE labels.5 LE SSERAFIM’s debut was sleek and minimal almost to the point of oversimplicity (almost), and they’ve continued to make their bones with pared-back versions of various house genres.6 (Don’t get me wrong, I like LSF.) I’ve already written here about what copying NewJeans’ blend of stripped-down drum and bass, mumbaton, and other Y2K-era genres has done to groups like STAYC. And HYBE has even managed to take fromis_9, previously purveyors of hyper-maximalist (or just hyper), melodic pop, and give them progressively more restrained, chic dance-pop songs. (Although “Attitude”—the last of those links—still goes incredibly hard due to its harmonies and sonic choices.)

The influence of these groups’ success has been massive. It caused IVE to try cutting back their typical dance-pop production style. æspa tried this style on. So did TripleS. And the Jersey Club trend spurred by LSF and NewJeans—audible on Idle’s new album— has even managed to reach J-pop.7 But of course every trend needs a countertrend, and I wonder if recent boy group releases might be providing it. SEVENTEEN returned to “freshteen,” energetic songs. RIIZE debuted with an upbeat, hooky pop-rock song. WOODZ has leaned even harder into his hard-driving “alt-rock” image. TRENDZ are giving us upbeat, maximalist dance pop.

Of course there are exceptions both ways. YENA is still doing her pop-punk thing. Idle, too, are continuing to use pop-rock backings on Track 2 of every album. (Although the latest incarnation is slower and noticeably more muted.) And, to be fair, there’s still plenty of boring crap being made on both sides of the aisle. Trends and countertrends come and go but some things never change.

Also liked…

glass beach – plastic death

Phantasm with Elizabeth Kenny – Matthew Locke: Consorts Flat and Sharp

The Smile – Wall of Eyes

Lina – Fado Camões

Christoph Grab – Reflections: Oneness

What I’m Reading

I picked up a copy of Howard Bryant’s Rickey at RoscoeBooks last summer (that’s right, people walked on Roscoe Street before the Rat Hole was christened), put it down, and didn’t manage to pick it up until this week. I guess that doesn’t sound like the most ringing of endorsements, but I promise I don’t mean it that way: I almost never read biographies to begin with, and this one was well worth breaking the pattern for. (And coming back to!)

I think it’s fair to say that, for people my age and probably up to a decade older, Rickey Henderson primarily exists as a statistical spectacle and a Berra-esque source of punchlines. Although I’d heard an interview with Bryant that made it clear there would be interesting historical context in this book (more on that in a bit), I won’t lie—I was looking forward to learning a couple new funny stories to add to “I can see the En-tire State Building,” “Tenure? Rickey got sixteen year!” and the others.

In the end, I’m not sorry that Rickey turned out not to be that kind of book at all. All of the famous anecdotes, including the John Olerud helmet story that’s not even true, are in there, but the book is hardly a goldmine of undiscovered laughs. Or even when it comes to “known” quirks: Rickey, as it turns out, didn’t actually talk about himself in the third person all that much.

Instead, Rickey is much more about why we remember Rickey that way. You can probably guess some elements of the story already. A Black athlete who never prioritized school was bound to be pigeonholed in certain ways by the sports press of the ‘80s. Just the same, Rickey also sold himself as an onfield spectacle with his flair: the snatch catch, the jersey-picking home run celebration, and of course everything surrounding all thos stolen bases.

At this point, with Henderson so firmly ensconced as a “lovable legend” (Bryan Cranston longs for when players would “run like Rickey”) and inner-inner circle Hall of Famer (111 bWAR will do that), it’s easy to forget how controversial his persona and playstyle made Rickey. Ever-popular baseball Youtuber Bailey not only needed to learn what “hot-dogging” meant to ‘80s athletes (now there’s a word that pops up constantly in Bryant’s book, when quotating of contemporaneous sportswriters); he also seems a little surprised that quite so much venom was directed at Rickey at all, over and above even what you might expect for the players on the other side of his 1989 ALCS trouncing.

If anything, Bryant’s book does too good a job of laying out the criticism and obstacles Rickey faced. It’s not quite a hagiography, but the book does more or less always take Rickey’s side, occasionally verging on the defensive.8 That said, it’s hard not to agree: in hindsight, and probably even to a clear-eyed observer at the time, the sportswriters were being ridiculous about Rickey’s “lack of desire” to play or win.

Still, the best part of this book is surely how it lays out Rickey’s historical context. The gem is the opening 100 or so pages, which do a superb job explaining how Oakland became the way it did, and how so many great Black athletes came from it. Apparently the original subtitle had “Oakland” in it, and there’s still a map of the city as the frontispiece, highlighting the birthplaces of Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan, and Huey Newton. It’s poignant reading at a time when the city is just about to lose its last professional franchise (Rickey’s team).

The context of Rickey’s playing career itself is probably more familiar (and no doubt relatively fresh in the minds of many readers), so Bryant has a slightly lighter touch when it comes to presenting how free agency changed players’ relationship to fans, the destructive meddling of George Steinbrenner, or the impact of cocaine and other drugs on ‘80s athletes more broadly. It’s a tricky needle to thread giving enough to help the uninitiated without boring the diehards; I admire Bryant’s skill getting that balance right.

The other kind of context, within MLB itself, is also given in spades. The inevitable comparisons—Willie Mays, whose number Rickie took, and Reggie Jackson, who made a similar spectacle of himself playing for the same teams a decade earlier—are certainly there. More unexpected is a digression on Rickey’s “loud” play as compared to Joe DiMaggio’s slick onfield presence. And some of Rickey’s teammates really take a beating in the comparisons; José Canseco shouldn’t read this book. (Dave Stewart comes off great though.)

As you can see, there’s a whole lot in Rickey, but it wears it all lightly, and the writing crackles along for most of it. If nothing else, the opening chapters on Oakland are worth a read by themselves—and after that, you’ll probably want to keep going. I certainly did, even with a bit of a pause.

A few others:

Nature – Forget lung, breast or prostate cancer: why tumour naming needs to change

Vittles – The Fiscal Theme Park

Chicago Reader – The art in Chicago’s limestone

The Guardian – Chart toppers of 17th century revived by historians and musicians

Atlas Obscura – This Team of Indigenous Women Sculpts Stories in Snow

Sixth Tone – Flash Fiction TV: Why China Is Betting Big on Ultrashort Dramas

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

Which, as musicians like Benjamin Alard would have it, could just as easily be a piece for pedal harpsichord. Rather ironic that Harmonia Mundi (or was it Alard with a smile?) decided to title the tracks “Organ Concerto” anyway.

A structure that matches the “Legrenzi” fugue in the same key.

OK, impeccable taste for her time then.

Spohr’s Faust isn’t based on Goethe. The actual first Goethe Faust opera that I know of was written by an obscure Polish duke.

Blame the influence of PinkPantheress and her ilk, presumably.

It’s a crying shame, but also probably symptomatic, that LSF’s hardest-rocking track was one of the B-sides that wasn’t reissued on their first LP.

Fausto is recorded before Arsenio? Did you have that on your bingo card? Will listen to the Fado..Henderson was a gas...Oakland is a deep dive into many aspects of US History - there's a nice historical museum there...a good starting point...

So we really don't have a clear idea about Greek colors. Gage's chapter goes into it in some detail and doesn't come out with much clarity. I think the ps-Aristotle de Coloris postdated his book ...but won't give you much either. Noticing the odd contexts in which the topics on color come up (eg Aristotle saying that the object of vision is surface=chroma) should makes us suitably cautious about trying to parse the Greeks regarding music...

It's no accident that the bad taste in painting Greek sculpture comes from the likes of Burne-Jones...Winckelmann is to blame for the white...