Week 25: 22 April 2024 – “Little” Preludes and Fugues and Jubilate

Plus: Kidz Bach?, "Impossible" RIIZEs to the occasion, Peter Manuel's Flamenco, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

This week, I’ve been exploring Oji-Cree songwriter Aysanabee’s work. 2022’s Watin is a fascinating album, mixing styles and moods in ways that can sometimes be a bit startling. Start with Aysanabee’s baritone itself, which can be rich and soulful (“Seeseepano,” “We Were Here”) or reedy and piercing (“Long Gone”). Just the same, the backings include inspiration from soul (“Seeseepano,” “River”) blended with an extroverted indie rock sound (“Bringing the Fire,” “Ego Death”); I hope it’s not too crass to say that a song like “We Were Here” sounds a lot like Neon Bible-era Arcade Fire (fellow Canadians!), albeit with both nicer singing and significantly less cringeworthy lyrics. What will make you cringe, although in a fully intentional way, are the stories of residential school life and enforced cultural amnesia told by Aysanabee’s grandfather (namesake of the album) during the interludes. It’s heavy stuff but very effective, and a remarkably cohesive listen despite all the sonic diversity. Listen to him talk about his work here and here.

Week 25: 22 April 2024 – “Little” Preludes and Fugues and Jubilate

Please save applause for the end of each set

Ehre sei dir, Christe, der du leidest Not, BWV 1097

Nun freut euch, lieben Christen/Es ist gewisslich an der Zeit, BWV 734

Fantasia in C minor, BWV 1121

Fugue in F, BWV Anh.42

Prelude and Fugue in C, BWV 553

Prelude and Fugue in D minor, BWV 554

Prelude and Fugue in E minor, BWV 555

Prelude and Fugue in F, BWV 556

Prelude and Fugue in G, BWV 557

Prelude and Fugue in G minor, BWV 558

Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 559

Prelude and Fugue in B-flat, BWV 560

I’m not sure how it happened, but I think I messed up by putting “Ehre sei dir” here. It’s clearly a chorale text about the Passion (“Christ, to Thee be glory / for Thy bitter pain / on the cross of suff’ring / dying for our gain”), and seems to be listed under Good Friday or Passiontide in any relevant source. Oops.

Then again, could you blame me? This is yet another piece that doesn’t at all match what “we” nowadays would expect for Passion music. The hymn tune, with its insistent repeated notes, suggests a triumphant and somewhat bombastic arrangement, and that (I think) is what Bach gives us. I’m still not 100% decided about the registration or tempo, but I liked the result from this version:

Doesn’t sound very “Passion”-y at all. At least until the end, when the harmonies collide in a dissonant mass. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that the last few measures are full of “cross”-motives—this kind of thing:

I also don’t know what happened with “Nun freut euch.” There’s not much ambiguity about liturgical context in this case, given that this tune shows up in the Christmas Oratorio! To be fair, it’s a somewhat versatile text, appearing as well in cantatas BWV 70 and BWV 22, for weeks just before and just after the Christmas season. But we’re still months off in either direction. I guess this is a catch-up week.

At least that gives us chorales to play; I don’t think there are any organ chorales corresponding to Bach’s cantatas for Jubilate Sunday. That name, by the way, is a bit misleading (it’s derived from a chant not sung in Lutheran churches): since the readings for Easter 4 emphasize the journey from suffering to joy, and because early 18th-century Lutherans like Bach loved to dwell on suffering, cantatas like “Weinen, klagen” BWV 12 and “Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal” BWV 146 are mostly pretty grim fare.

Anyway, “Nun freut.” Unlike Buxtehude’s gigantic, masterful, and varied fantasy on the tune, this piece is short, breezy, uniform, and somewhat awkward. “Nun freut” is a perpetuum mobile layer cake: right hand in running sixteenths, bass in walking eighths, tune in slower notes as the tenor voice. The lower two parts (the left hand) almost work as a chorale setting by themselves, which is maybe part of why the right hand sounds so meandering, almost like idle noodling. It’s a weird part, representing a kind of melodic writing Bach normally leaves for running bass lines.

Funny that the same awkwardness is less apparent in the two “questionable” pieces that round out this set. To be sure, the Fantasy in C minor (almost definitely by Bach—he wrote out the only surviving score and didn’t put anybody else’s name on it) can sound a little bit harmonically random in a few places, but on the whole it’s a very fluent and even charming piece with nice imitations of (pre-Vivaldi) Italian instrumental styles. Some of it is reminiscent of the Canzona BWV 588, although the structure is almost the reverse: instead of taking a cut-time theme and then putting it into a dance-like triple meter, this piece starts out in a lilting 6/4 and then switches to square common time for the last section.

As for the Fugue in F—who knows who this piece is by, given that its only source is from decades after Bach’s death and attributes it to “Joh. Sebastian Bach ? [sic]”. Peter Williams calls it “post-Bach” and detects some potential influence from Handel. Could be! It doesn’t sound a ton like Bach. But then again Bach doesn’t always sound like Bach, and this piece is well within the bounds of his style. It’s also a very solid fugue, even a fun piece.

Oh and—the F-major Fugue might not even be for organ. But it’s not like that’s ever stopped us either.

And now for the motherlode of “questionable” pieces. Along with the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, the “Eight Little Preludes and Fugues” have to be the most famous of Bach’s “contested” organ works. Some of the reasons for doubt are the same. There’s no surviving manuscript in Bach’s hand, and the oldest surviving source (this time from Bach’s lifetime, unlike the D-minor Toccata) only has the somewhat discouraging attribution “di J.S. BACH. (?)” (The question mark was probably added later, but so was the composer’s name itself.) The pieces have some errors of counterpoint (parallel fifths and octaves) and yet are stylistically so “up to date” that it makes no sense to chalk these mistakes up to youth or inexperience. There are some truly unusual moments—is that a quotation of “Jesu meine Freude” near the beginning of No.2? What the heck happens to the meter at the end of No.7?—and the style often sounds much more like Handel than like Bach, especially in the fugues.

All of that is true, and these pieces definitely are unusual. Still, discussion around them can make me feel like I’m taking crazy pills. Take the counterpoint errors, for example: in these pieces, they’re not incredibly common, not particularly egregious or obvious, and not as bad as many of the clunkers that Brahms collected in his notebook of parallel fifths and octaves:1

Other of Brahms’ examples come from the literal B-minor Mass and St. Matthew Passion. Are we going to question their authorship on the basis of parallels?2

As for other aspects of their style—it’s true that these pieces sound pretty different from pieces like the “Wedge.” But they aren’t so far from the “Corelli” fugue, from Vivaldi’s fugue in the D-minor concerto, or even from the final fugue of the E-major Prelude. The quotation of “Jesu meine Freude” does stick out, but it could just be a coincidence—it’s just a scale!

And if you want to attribute these pieces to somebody else, you have to reckon with the fact that they have a lot in common with Bach’s music. First the complete absorption of modern Italian style: the first prelude sounds a whole lot like the fifth trio sonata’s first movement, and uses repeated notes in the pedals to an extent that I most associate with Bach’s concerto transcriptions and imitation-Vivaldi organ works. (BWV 541, we’re getting to you soon.) And speaking of pedals, while these are definitely not the hardest Bach organ pieces, they also have much more involved footwork than any organ piece by the other candidates that have been proposed (J.L. Krebs, J.C.F. Fischer).

Maybe these are pieces by a gifted, but anonymous, musician in the Bachian orbit. It’s not at all impossible: What would we say about Prince Ludwig Ernst’s music if it had come down to us anonymously? How many more Ludwig Ernsts were out there? But at a certain point, if our only alternative is to postulate some otherwise completely unknown composer, maybe it’s better to go with the surviving attribution, at least for now.

In any case, putting these pieces under the Bach rubric has the benefit of giving them a wider audience—and they deserve it. I meant what I said when I compared the first prelude to Trio Sonata No.5, my favorite organ piece. And it’s not the only prelude to successfully adopt instrumental styles: No.4 is an adorable little galant thing while Nos.2 and 8 have some nice concerto-like elements. Other pieces (No.6) combine Italian-style harmonies and some string figurations. The fugues are also refreshingly concerto grosso-like, or even (No.5) reminiscent of some choruses from Messiah. The pieces may be “little,” but that works in their favor: unlike so much of Bach, these preludes and fugues are breezy, laid-back, and concise. Maybe that’s why Bachians don’t like them.

Childs’ Play?

Honestly, I think I may not have done a good enough job above in emphasizing how dismissive Bach scholars have been of the Eight Little Preludes and Fugues. Peter Williams, astoundingly, compares No.4 unfavorably to the Pastorella, a canonical “worst” Bach organ piece. The supplemental Volumes 10 and 11 of Bärenreiter’s edition of the complete Bach organ works include all manner of bad and deeply questionable pieces (in addition to “restoring” pieces like the “Gigue” fugue, the A-minor fantasy, and the Kleines harmonisches Labyrinth), but resolutely leave the “Little” Preludes and Fugues out. When you’re publishing the F-major fugue for the first time (there’s a reason it’s “BWV Anh.” and not straightforward BWV) but still leaving out the “Little” Preludes and Fugues, I’m inclined to think you have some kind of agenda or bias.

I have to wonder if part of the prejudice might go along with the pieces’ nickname: “Little.” Given that this is music practically every organist learns as a beginner,3 and that it’s almost all short, sweet, and catchy, I suspect that there’s some temptation to see it as “juvenile” and therefore less than dignified. Take this blog post that’s inexplicably linked from the pieces’ (atrocious) Wikipedia page. It would be hard to find a better example of all the “Bach ideology” stuff I’ve complained about, here being used as a bludgeon: the essence of Bach, so they say, lies in extensive, difficult pedal parts, or in sheer length and intricacy, or in counterpoint tricks. These pieces don’t fit, so they must not be Bach.

Beside the fact that I dispute some of the charges (they’re not the A-minor fugue, but these pedal parts are pervasive, independent, and use a wide range of techniques), I think that they’re rather missing the point. It’s very easy to find indisputably authentic Bach that goes against all three of these trends, and not just early pieces. It’s not like Bach “aged out” of writing less complicated music.

Most obviously, Bach had (just a few) children of his own, and expected them to become musicians. We have lots of “Bach for kids,” especially in the Klavierbüchlein for Wilhelm Friedemann. And I don’t see too much of a distance between these little preludes and fugues with pedals and those little preludes for keyboard only.

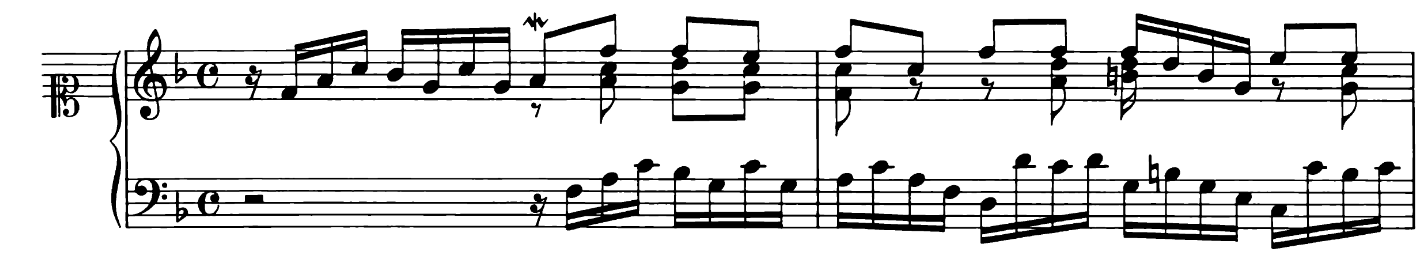

To claim that these pieces might have been written for beginners is not exactly breaking new ground, but maybe it is a bit novel to assert that those little preludes, your first “real pieces” after a few months of piano lessons, are actually really great, and as worth taking seriously as anything else by Bach. From the Wilhelm Friedemann collection, we start out with the C-major prelude BWV 924, which systematically and beautifully introduces tension-ratcheting rising sequences, followed by relaxation in the other direction:

This, in miniature, is the kind of “plot” that Well-Tempered Clavier preludes often take.

The D-minor prelude BWV 926 is an exercise, both compositionally and for the performer, in the subtleties of bringing across cross-rhythms:

Those highly visible groups of three eighth notes cut the measure in half, and thus work against the ¾ meter in ways that are a nice little challenge to keep in check.

Or take the two F-major preludes BWV 927 and 928, which introduce the Italian string style in both figuration and harmony:

and

These pieces are all tiny, but they’re also all gems, delightfully satisfying and often quite catchy.

I imagine that that attractiveness goes along with the pieces’ pedagogical purpose. Others of his “teaching pieces,” especially the Two-Part Inventions, are also among Bach’s most enjoyable music. To say this is not to assert that Bach was dumbing his music down for beginners or kids. Obviously, it’s not a bad goal in general to make your music fun to play and hear, but it’s especially important for motivating beginners. (The Three-Part Sinfonias, substantially more difficult than the Inventions, seem to try a lot less hard to be memorable.)

It’s also not “dumbing down” if these pieces aren’t as intricate as the “Wedge” or the “St. Anne” fugues. Not only do they have to be technically simpler to be for beginners—there are limits on what devices it’s reasonable to use in a short piece. Scale matters: it might just sound weird if Bach tried to build up quickly to massive stretti or harmonically intricate climaxes in this music.

All of this, I think, goes for the organ Little Preludes and Fugues. Most of the preludes are more tuneful and fun than all but a few of the “big” Preludes and Fugues; and if the fugues don’t show off too much virtuosity in counterpoint, that’s in large part due to their small scale. Whoever wrote them did an admirable job at writing a cute little teaching collection full of entertaining music. It doesn’t have to have been Bach, but we know that Bach was capable of such things.

I can advocate for this music until I’m blue in the face, but I doubt I’ll be convincing many organists to program these preludes and fugues in recitals. The incentive structure of classical music performance works hard against that kind of programming. For starters, the performer is almost always under some obligation to show off a bit, and music for kids or beginners is almost definitionally not very flashy. It also may be too familiar, inciting an “I can/did play that!” reaction in the audience regardless of any differences in execution. And, as I’ve been arguing all along, people have musical prejudices against Kidz Bach, partially driven by the kitschy and genuinely dumbed-down nature of a lot of later music for children. So, programming childrens’ music is actually the ultimate flex. (I heard Daniil Trifonov, at probably the best piano recital I’ve ever attended, start a program off with Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. To be fair, he ended with Gaspard de la nuit—he doesn’t have anything left to prove.)

But all of this assumes that there’s an obvious line between “kids’ music” and “adult music.” That may have become true in the 19th century, but it assumes an idea of “childhood” that was only just coming into shape in Bach’s lifetime. Philippe Ariès may have badly overstated the case, but it does seem like children were seen more like “little adults” in the earlier 18th century than they are now, and certainly the idea of “kids’ music” (especially music that has to “sound like childhood”) just doesn’t seem to have really been a thing.

This is especially evident in Bach’s other collections. The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, famously bills itself as “for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning and especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study composed” (italics mine). Bach titled his published collections “keyboard practice” (Clavierübung) in a way that is again presumably aimed at multiple audiences.

No organist would apologize for including music from Clavierübung III on a recital, but I do think there’s a certain reticence to program all but the “biggest” entries (“O Mensch bewein”; “Christ ist erstanden”) from the Orgelbüchlein (among Americans at least; it seems like French organists in particular don’t care). Not that organists necessarily think that those are “kiddy chorales,” but that “-lein” in the collection’s title is probably still a factor. The chorales’ miniature size and the collection’s frequent use to teach beginners (even if some of the entries are about as hard as Bach organ music gets) might give rise to some of the same programming queasiness as the Two-Part Inventions do. Better play another Vierne symphony instead.

I guess I would urge organists (and other musicians) to resist this tendency. (And definitely to resist playing Vierne symphonies.) I think there’s value to organizing programs around substantial pieces, but there’s also value to playing charming and excellent music, especially when you can organize the pieces into a slightly more imposing set of eight. Don’t be afraid to play the Little Preludes and Fugues, even if you think they’re just

What I’m Listening To

Les Amazones d’Afrique – Musow Danse

I was happy enough to see that Les Amazones have a new album—the previous two are as fantastic as you might expect from a project featuring Angélique Kidjo and a singer surnamed Keïta—but I was even more delighted when I actually put this one on. Much as I liked Les Amazones’ earlier music, the production styles (congotronics, dub) could have a bit of a tendency to get in the way of just listening to their voices, and of just having a good time. Musow Danse, delightfully, has neither problem.

It mostly achieves this by leaning much harder into pop. Tracks like “Queen Kuruma” and “Mother Murakoze” bring a variety of global dance beats (do I hear some moombahton influence?) to bear on bold synth lines and big vocals. And those vocals really shine this time around, whether solo (e.g. on “Espérance”), in unison (“Kiss Me”), or in harmony (“Musow Danse”). It’s just an album full of great songs and great performances; a perfect point of entry for a spectacular group.

Nia Archives – Silence Is Loud

I’ve complained a lot here (should I just end the sentence there?) about the impact of the drum’n’bass wave in pop music over the past few years. So many imitators of PinkPantheress and her ilk have turned out so much bland, empty music, and their imitators in turn have jumped on the trends—including acts previously known for out and out pop. (I’m not just talking about NewJeans’ influence, but I’m not not talking about them.)

So it’s good to get a reminder of how great actual drum’n’bass can be when done right. Not that Nia Archives is a “revivalist” or even particularly “traditional”: songs like “Cards on the Table” are boldly melodic, and there are massive synth and guitar sounds on songs like “Tell Me What It’s Like?” This, like all that music I love to whine about, turns jungle into pop. But it’s not sleepy, TikTokified bedroom stuff. Turns out that, when using material as high-energy as drum’n’bass’s manically sped-up beats, bringing some of that same intensity to bear on the rest of the production pays dividends. The album gets a little samey by the end, but even the first few tracks make a big statement. I hope HYBE producers are listening.

John Wilson and Sinfonia of London – Bacewicz, Enescu, Ysaÿe: Music for Strings

I don’t really know how John Wilson and his orchestras do it. They seem to come out with something like five or six albums a year, all while most of the Sinfonia’s members are busy performing with other ensembles. The repertoire tends to be from the first half of the twentieth century, and Wilson brings something of a big band director’s polish and (muted?) flair to the music. (He’s something of a big band director himself.) It always sounds wonderful, and the performances are engaging, even if you don’t love the music. And that’s pretty much the norm for me, considering that Wilson likes to record music like John Ireland's orchestral works and a diligent reconstruction of the original version of Oklahoma!

This album is another of those, but with a saving grace in the third act. The Ysaÿe is…fine (what better could you expect for obscure Ysaÿe?), and the Enescu is a nice piece that’s been very smartly arranged for string orchestra.4 But they both pale before Bacewicz’s Concerto for Strings, which I don’t think I’ve ever heard played quite this well. That’s saying something, considering that this piece has basically become her musical calling card—it’s for an “accessible” ensemble (string orchestra with soloists), musically no more demanding than the two staple Bartók orchestral pieces, and, at only 15 minutes, won’t overstay its welcome with even an unadventurous audience. This piece isn’t lacking for recordings, and good ones.

That all sounds much more backhanded than the Concerto deserves. It’s definitely the best I’ve heard of Bacewicz’s neoclassical period, and if it doesn’t quite have the austere rigor of the last two string quartets, it has all of their intensity and good ideas. Wilson’s interpretation really brings out the rhythmic drive of the outer movements, their metrical playfulness and neo-Baroque chugging; and his ensemble’s sheen is perfect for the slow movement, in both its pastoral framing passages and the wailing laments at its core. It’s a great performance. The only downside is that it makes the first two pieces look bad by comparison.

RIIZE – “Impossible”

Seven months and six songs into their career, I no longer have any idea what RIIZE’s musical identity is supposed to be, or if they even have one. I guess it would be foolhardy to expect an SM Entertainment group to stick to one sound, but this is whiplash even by their standards.

Delightfully, SM think that they’ve announced a musical concept for RIIZE:

RIIZE will play its unique genre ― ‘emotional pop’ ― that sheds light on various emotions and experiences the seven members will have as they attempt to achieve growth. Our ultimate goal is to become a top-tier act on the global music scene.

Ah yes, the unique and novel concept of pop based on emotions. I wonder how nobody else thought of that.

Jokes aside, maybe the unifying thread of RIIZE’s music so far is an element of nostalgia. Not that throwbacks are anything new in K-pop, but their music is somewhat resolutely anti-trend, and often avowedly about the past. That starts from predebut single “Memories,” not only (duh) in its title, but also in its somewhat old-school, full-blooded synthpop chorus. A chorus that’s notably major-key: there’s a decent amount of big, bold pop still being made by K-pop boy groups, but it often tends to be dark or moody stuff. In that context, “Memories” is a breath of fresh air. (Shame about the verses.)

Even more so for debut track “Get a Guitar,” a very good song that (duh) overtly hitches its wagons to old-fashioned musical styles, maintaining that refreshing, poppy style over a bed of disco-funk guitars and synths. It never quite goes anywhere, and the chorus isn’t quite big enough for my taste (at least in a song like this), but it’s groovy, slick, and fun. Again (and wisely for a brand-new group in a company whose active male groups currently total over 50 members), it just feels super fresh.

Couldn’t say the same about follow-up song “Talk Saxy.” Although it maintains the “name an instrument and go slightly retro” concept of “Get a Guitar,” this song is a lot more color-by-numbers, both brash in vaguely grating ways and too slow to be really energizing. (Recent B-side “Siren” is also pretty formulaic but has much more of a musical backbone, and probably kills at live performances.) And ballad “Love 119,” while also going for a “nostalgia” concept, also uses a shout-chorus formula that might as well be pasted from NCT, without the hooks of a song like “Hot Sauce.”

If you’re not keeping track, that’s actually every RIIZE song to date. Which brings us to “Impossible.” In some ways, this song keeps up the trend, giving us a throwback house track with nice instrumentals (that piano loop) and a pretty good chorus. And it’s a throwback not only to early 2000s clubs, but also to an earlier era of SM sounds: producers LDN Noise composed several songs in this vein for SHINee about a decade ago.

I think “Impossible” isn’t half bad, but it’s practically impossible for me to hear without making the comparison to those SHINee songs. “View” is the classic:

Obviously Jonghyun’s lyrics are lightyears better than the pile of clichés that is “Impossible”; but that’s hardly an issue for a dance track. And it’s no shame that RIIZE’s vocals are worse than SHINee’s—talk about a tough comparison. (SM’s vocal effects and processing on “Impossible” also really grate on my ears, so it’s not necessarily the singers’ fault.) But “View” is just…way more of a song than “Impossible.” The beat is more fleshed out and not masked behind a wall of hi-hat; there’s at least some harmonic interest; the verse and prechorus have serious melodic direction; the chorus is just one long series of great hooks; and the bridge is a pretty big value-add.

Even non-single LDN Noise SHINee tracks feel like an improvement on “Impossible.” Take “Shift,” a song that doesn’t quite have the hooks, but has beats, chords, vocals, and structure that I would kill for in RIIZE’s song. “Impossible” feels a bit like a victim of the (in Korean English) “easy listening” trend, songs that sit comfortably in the background without asserting themselves too strongly. It’s a pretty good dance track but it’s not gripping in the ways that I know LDN Noise and SM are capable of.

Look, it’s not really fair to compare RIIZE to SHINee. RIIZE probably aren’t going to get shouted out publicly by Barack Obama anytime soon. They’re half a year into their career, while Odd was a Year-8 change of creative direction for SHINee. There will never be another Jonghyun. And, to RIIZE’s credit, there’s no song like “Get a Guitar” (or really even “Memories”) in SHINee’s discography. They’re their own thing and deserve to be evaluated as such.

But this is sort of what SM is setting them up for, just like they set up the NCT comparisons with “Love 119.” It’s nowhere near as bad as what B.E.P. did to “FANCY,” but when you have a producer retread their old sound for a new track, people are going to listen through the lens of what they know. The new song can’t just be good. It has too much to live up to.

Still, “Impossible” is ultimately pretty good, and it’s just a prerelease for the upcoming mini. If this is the second- or third-best track, then that’s a positive sign for the lead single. Who knows; maybe they’ll even get a guitar again.

Also liked…

Kristo Rodzevski – Black Earth

Shabaka – Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace

Bnny – One Million Love Songs

ODD 陈思健 – 上三滥

Christian McBride and Edgar Meyer – But Who’s Gonna Play the Melody?

girl in red (yes, really) – I’M DOING IT AGAIN BABY!

Farah Kaddour – Badā بَدا

What I’m Reading

Peter Manuel writes solid, useful books that I suspect appeal a lot more to people like me than to most of his ethnomusicologist colleagues.5 He’s interested in a lot of issues of musical style and structure that appeal to my theorist brain, and much of his work has thus focused on music somewhat independently of the culture it’s embedded in. And he’s also actively interested in comparison, having done serious work in music of the Caribbean, India, and Spain.

It’s the Spanish work that’s finally made its way into book form with Flamenco, an excellent and comprehensive book that I imagine will be the English-language standard on the subject for decades. (It’s been over 60 years since the previous standard book, by Donn Pohren, came out.) And true to form, this is very much a book “about the music.” If you align the book’s three parts (“history, forms, culture”) with the three standard divisions of American music scholarship (musicology, theory, ethnomusicology) the page counts would put Manuel squarely in theory land with a healthy dose of history. “Culture” is covered in a reasonably thorough fashion, but it’s not the centerpiece.

I know I’m biased, but I think the “theory” portion of the book is the star for more than one reason. It’s easily the best survey of flamenco harmony, rhythm, and forms in English, dealing sensibly with a number of disputed theoretical questions (“How do you count Bulerías?”). At the very least, any reader who doesn’t already know a lot about flamenco will probably want to read the “forms” part first: I imagine the history section is kind of incomprehensible if you have zero or even basic knowledge of flamenco forms and terminology. (I came in with a barebones acquaintance of the most famous forms and found Chapter 2 pretty tough sledding.) Conversely, you don’t need to know who the people being referred to in the “theory” section are to learn about the music.

That’s not the only “ordering” difficulty with this book. To be fair, not every survey of a topic has to be textbook-like or pop-nonfiction-like. Instead, this book is something like a survey history coupled to a descriptive grammar (a sadly out-of-fashion form of ethnomusicological writing).6 It’s a lot of work to learn a language from a descriptive grammar, and you probably need to know some stuff already or get some outside help. Not that anybody thinks they’ll be “learning flamenco [performance]” from a book, but if you really want to get what’s going on here, you’ll probably spend a lot of time pulling up recordings.

That said, the writing isn’t overly technical, and the historical section in particular doesn’t assume any prior knowledge; Manuel is willing to cover the basics about Spanish history, Gitano racial and cultural politics, and the musical currents that have swum around flamenco. That part of the book (Part 1) is really great, and sensitively broaches a whole bunch of extremely thorny and completely undecidable questions. Manuel, with his broad training and research, is probably better equipped than anybody to assess the potential relationships of flamenco to North Indian, West Asian, Balkan, North African, and Afro-Caribbean musics. (And he’s willing to give more elaborate technical discussions in boxes for people like me.) His discussion of links to Afro-Caribbean music is especially enlightening. Maybe he’s biased by his research interests—but he makes a convincing case.

So: Flamenco is ultimately an essential, sensible, readable, and somewhat frustrating book. You won’t find out too much about “culture” (or dance, sorry) in it, but it’s a great introduction to a whole lot of important historical figures, recording artists, song-types, and musical terms. If only ethnomusicologists (or, for that matter, most music theorists) cared…

A few others:

NY Times – Faith Ringgold Perfectly Captured the Pitch of America’s Madness

London Review of Books (Terry Eagleton) – Where does culture come from?

The Guardian – How cheap, outsourced labour in Africa is shaping AI English

Block Club Chicago – Death Behind The Wheel: How The CTA Failed A Driver In Crisis

Harper’s Bazaar – I Think This Will Fix Me: Wellness is everywhere. But just how well does anyone need to be?

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

The examples are from Paul Mast’s edition in The Music Forum V.

Yes, yes, there are holograph manuscripts of those pieces, as opposed to “J.S. Bach. (?)”; I’m just making a point.

Although my first teacher, Dr. Quinn, insisted that I skip them and go straight to “real Bach.” I never got to ask if he meant in terms of certain authorship or if it was about music that wasn’t “for beginners.”

I’m sorry to say that neither this album nor Cristian Mǎcelaru’s new set of the complete symphonies have really improved my opinion of Enescu, although the choral finale of the third symphony was a fun and unexpected touch. Romanians, please have mercy.

It’s dated as hell by now, but I learned a lot from Popular Musics of the Non-Western World in particular.

The prototype modern examples for me are Paul Berliner’s books.

Eagleton. Blathering on like that about the blindingly obvious is enough to make you go back to Culture and Anarchy with some relief (Arnold's prose is exemplary). These days though, the action is in the history of settled and nomadic people and their interactions. It's good intellectual progress that culture is no longer the exclusive province of settled folk. At least two cheers. And now we need to wonder how culture comes about without cultivation. A. Smith teaches that the parts of price are the wages of labor, the profits of stock and the rent of land. No one agrees any more, but no one has reformulated that trinity (Schumpeter adds to it) to replace rents. In fact 'rents' have become more important in economic theory as time has gone on. M. Sahlins has Stone Age Economics (not just a Second City gag) and that might be a starting point. What does economics (or bowing to Eagleton, labor) look like when you abstract from the nomadic/settled distinction?