Week 21: 25 March 2024 – “Erbarm dich mein”: Palm Sunday and Good Friday

Plus: What's OK to change in Bach? STAYC's take on "Fancy," Wittgenstein retranslated, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

Chicago native Bill Buchholtz-Allison is an organist, but don’t hold that against him: he’s mostly known for beautiful and thoughtful playing on various Native flutes. That seems to be a cultural reclamation project of a kind. Although he’s Algonkin by descent, Buchholtz was adopted by a White family and was raised mostly around rock and church music. It took a Chicago-area Lakota elder pressing a flute into his hands for him to switch paths.

Perhaps wisely, it seems like Buchholtz has mostly avoided labeling his music as particularly “traditional,” instead focusing on spotlighting the instruments themselves and their musical possibilities. (You can read a bit of him talking about the flutes here.) So his Soundcloud labels his songs as “Native American Modern contemporary music,” which—fair enough. Regardless, I do think he’s doing a very fine job of advocating for the instruments and the cultural forms they represent. Not least through his playing: the tracks on Soundcloud and his website are all lovely, showcasing not only the bewitching timbres these flutes can conjure, but also their sonic variety, from low and smooth wood-dove sounds (“Beginnings”) to more intense, almost reedy calls with much harsher attacks (“1/26/2012”), and everything in between (“Father”). Now to find a copy of his CD….

Week 21: 25 March 2024 – “Erbarm dich mein”: Palm Sunday and Good Friday

Please save applause for the end of each set

Christus, der uns selig macht, BWV 620

Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund’, BWV 621

Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge, BWV 624

Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 623

Erbarm’ dich mein, O Herre Gott, BWV 721

Herzlich tut mich verlangen, BWV 727

Kleines harmonisches Labyrinth, BWV 591

i. Introitus

ii. Centrum

iii. Exitus

Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen, BWV 1093

Christe, der du bist Tag und Licht / Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 1096

Als Jesus Christus in der Nacht, BWV 1108

Prelude and Fugue in G minor, BWV 535

Originally, I thought about trying to separate this concert into two halves, Palm Sunday music followed by Good Friday. What I hadn’t realized was just how little Bach music there is that’s specifically for Palm Sunday: in his time, the sixth Sunday in Lent seems to have been much more relevant as Passion Sunday, and all of the Lenten restrictions on musicmaking apply. There’s only one cantata—BWV 182—for Palm Sunday, and even that piece was written for the Feast of the Annunciation. (As this recital shows, March 25 does have a tendency to fall within Lent.)

If there’s a single piece that made me want to adopt the “two-part” plan, it’s “Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ.” This piece is about as close to chamber/orchestral music as Bach’s chorale preludes get, adopting the rhythms and style of a polonaise. It’s downright festive music, as surely befits, um, this text:

Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ,

dass du für uns gestorben bist

und hast uns durch dein teures Blut

gemacht vor Gott gerecht und gut

Lord Jesus, we give thanks to Thee

That Thou hast died to set us free;

Made righteous through Thy precious blood,

We now are reconciled to God.

…Yeah. Passiontide music for sure, and yet another reminder that Bach’s attitude toward death (“Alle Menschen müssen sterben” anyone?) was pretty different from most of ours. The piece is great though: toe-tapping rhythms, effective harmonies, densely woven counterpoint. And the tune is awfully catchy, even folksong-like. Maybe you’ll be whistling “und hast uns durch dein teures Blut” on your way out.

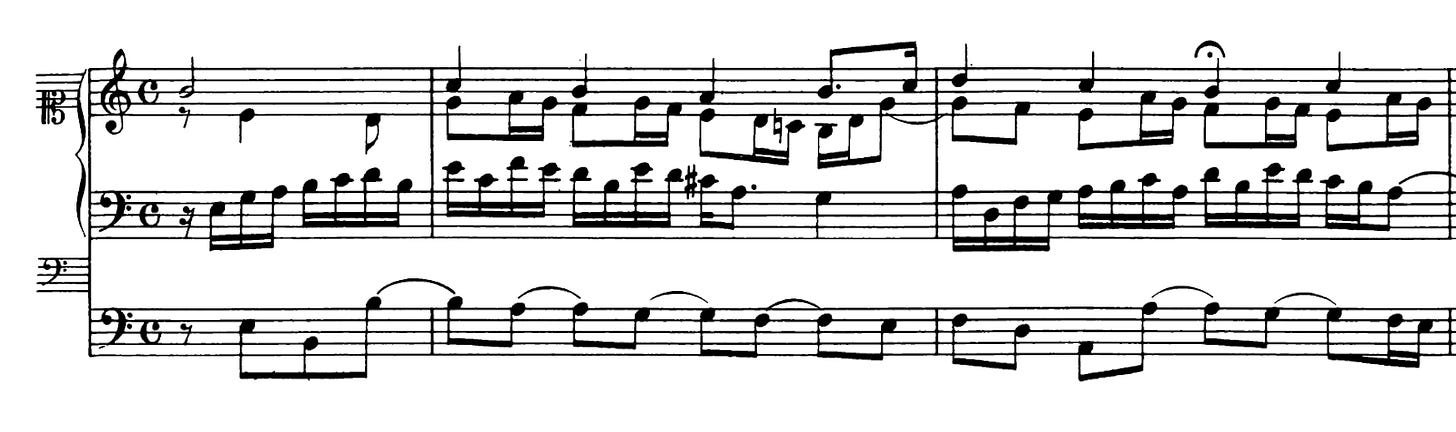

Some of the same foot-stomping rhythmic insistence also shows up in “Christus, der uns selig macht,” a tune that might be familiar from the St. John Passion. This take on the hymn is another chorale sandwich, with the tune in canon between the soprano and the bass:

The repeated notes in the tune are forceful enough, but the added syncopations in the inner voices make for an even stronger rhythmic effect. But not throughout the piece; this texture alternates with drooping chromatic laments:

Unlike the truncated “Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” it’s hard to miss the theological relevance of “Da Jesu an dem Kreuze stund’” from the title (even if it’s not obvious that this hymn is mostly a setting of the Seven Last Words). As you might expect, the music is pretty harsh, with a pedal part that stays syncopated for almost the whole piece:

The pedal part even maintains those dissonant suspensions through the ends of phrases, making it hard to know where the articulations are, and giving almost no place to rest. (After those rests in the first measure, no voice gets a chance to catch a breath.)

Even more breathless is “Hilf, Gott,” which has some of the same bass syncopations, but adds a running part in triplets:

Like “Christus, der uns selig macht,” this piece is a canon, mostly at the fifth, although it can be a bit hard to hear how the two upper parts relate to each other. Honestly, I find it hard to understand almost anything about this piece; more about it below.

A few times when I told people about preparing this series, I got questions about individual pieces. Mostly “Are you doing the Art of Fugue?” (sadly not), but a few questions about which “questionable” pieces to include (yes, I really did have a friend ask if I was going to play Toccata and Fugue in D Minor).

Those were mostly fun conversations, but I did manage to really embarrass myself once. When asked “Oh, so you’re playing that piece “Erbarm’ dich”?”, I tried for about 10 minutes to insist “You must mean “Erbarme dich” from the St. Matthew Passion?” (Sorry James!) Shows how much attention I paid to titles when learning the lesser-known chorales.

Still, as that conversation should indicate, “Erbarm’ dich” is pretty well-known by “lesser-known” standards. Enough for Yo-Yo Ma to have recorded it at least. And why not? It’s a beautiful piece, and certainly stands out among Bach’s organ works. This is not Baroque keyboard writing:1

All those repeated chords look a whole lot more like string parts, and maybe this is an arrangement of a string piece, whether by Bach or not. (That uncertainty about authorship applies to both the piece itself and its potential arranger.) But the very weirdness of this piece—all the reasons to think that it’s “not organ music”—also makes a fascinating contrast to the other Bach organ works. And it doesn’t hurt that it’s a drop-dead stunning piece, full of harmonies that’ll break your heart.

So is “Herzlich tut mich verlangen.” Listeners of the St. Matthew Passion know this chorale all too well (under the title “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden”—“O Sacred Head Sore Wounded”), and its four settings in that piece show how sensitive Bach was to its musical possibilities. It’s also hard not to get the impression that Bach also just really liked this tune. Certainly, BWV 727 gives that sense, decorating the tune a bit but focusing more on giving as beautiful and expressive a harmonization as possible. If it were in the Orgelbüchlein, I bet this would be a pretty famous piece.

I’ll be straightforward here: the Kleines Harmonisches Labyrinth is probably not for organ, it’s probably not by Bach, and I bet it wasn’t originally called “Kleines Harmonisches Labyrinth.” The attribution may boil down to this brief moment in the Centrum:

That’s thin evidence at best: it could be an homage from another composer, a signature from a Bach son, or even a pure coincidence. All of the surviving sources are really late and barely linked to Bach at all—thus my questions about the strange title. So, the fact that the manuscripts all happened to put Bach’s name on the piece could be wishful thinking, willfulness, or pure fancy. Still: they did all agree on the composer. (Including, apparently, a copy that Mozart owned.)

Similarly, the only reason this piece is filed under organ music is this single indication:

That’s also not great evidence; it could just be indicating a pedal point. (Although, how often is that actually marked?) There’s barely any need to use pedals, and the organ hardly had a monopoly on pedals among keyboard instruments. All I can say is that it can work on organ.

That’s all reason enough to be dubious about this piece. Then there’s the style, which mostly sounds nothing like Bach, and in some ways resembles later eighteenth-century keyboard music. The writing can be kind of awkward and weird, and basically none of the melodic material is memorable. A lot of scholars really don’t want this piece to be by Bach.

Others really do. That’s because the Labyrinth fits a lot of the characteristics people want to attribute to Bach: it explores all the keys like the Well-Tempered Clavier; it has an intricate fugue at its center that makes no concessions to the listener; overall, it can sound more like an “intellectual” exercise than a piece of music. (Doesn’t the title make it sound like a piece you’d want to be by Bach?) It’s hard not to hear the Labyrinth “merely interesting.” Bach the avant-garde; Bach the mathematician; Bach writing for posterity, or even himself.

I’m a bit more inclined toward the “dubious” camp, but even if you agree that this piece is unlikely to actually be by Bach, you still have to explain why it exists. After all, the other proposed composer candidates (Heinichen liked to write pieces that take a spin through the range of keys) are an equally bad stylistic fit. This piece is pretty much unique, and whoever wrote it very possibly did have that image of Bach in mind. Even if this piece isn’t by Bach, his fingerprints are all over it. Good enough reason to give it some airtime.

To close this set, three more chorales from the Neumeister collection. “Christe, der du bist” is a relatively straightforward, if very nicely executed chorale fugue; and “Als Jesus Christus in der Nacht” is a similarly polished figuration chorale in two verses, sounding almost like something out of the Orgelbüchlein. If anything, those pieces are unusual for their rhythmic consistency and overall polish—unusual, that is, among the other Neumeister Chorales. Later Bach all pretty much sounds like that.

This version of “Herzliebster Jesu” is a bit closer to the more raw style of some of the other Neumeister Chorales. If you know this tune from the St. Matthew Passion, you may be a bit surprised at the tone of this version:

I may have gone just a tad overboard on the punchiness in that take, but the rhythms (and the cut-C time signature) do call for something a lot more upbeat than what you might associate with this hymn. The ending of the piece sounds almost like a toccata:

Although not a Bach toccata. The left-hand part that accompanies the chromatic descent in m.33 (a very cool Bachian change to the hymn tune!) sounds for all the world like Sweelinck, which is to say like music that was almost a hundred years old when Bach was writing these pieces. I doubt that there was an intended “retrospective” effect (or that Bach even had any direct knowledge of that music), but it shows just how much stylistic ground Bach covered in his lifetime. And as an exemplar of this “early” style, I think this piece is pretty great. Tuneful, fluent, rhythmically distinctive, and harmonically memorable. It might not sound a ton like later Bach, but (to state the obvious) not all good music has to.

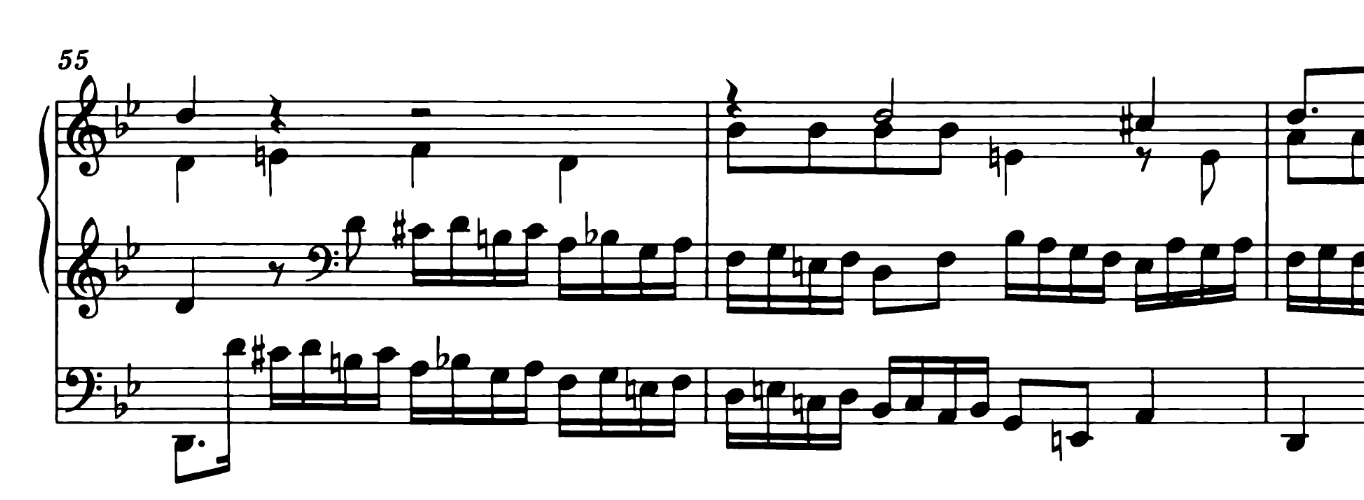

BWV 535 doesn’t have a ton of name-brand appeal—this G-minor fugue is neither “Great” nor “Little”—but it’s an exceptional piece in a number of ways. I don’t want to bury the lede, so let’s start with its most famous idiosyncrasy. Here’s the first real pedal entrance in the Prelude:

And here’s the last statement of the fugue subject:

Déjà entendu?

Look, that phrase in the pedals is pretty commonplace, so this seeming flashforward could be a coincidence. But that seems a little hard to believe: there’s an earlier version of this piece whose prelude completely lacks anything like this, so it seems reasonable to guess that Bach may have had this idea during the rewriting process. It’s unique among his works, and really sounds much more like something a nineteenth-century composer—when people started to get more obsessed with “organic unity”—would do.

The rest of the piece is more by-the-book. After its ruminating beginning, the prelude explodes into stylus phantasticus fireworks for most of its duration, including two straight pages of harmonic confusion at top speed:

It’s hard enough to play this stuff at the requisite thrilling speed, but making this chromatic descent through an octave not sound samey or repetitious is probably an even greater challenge.

As for the fugue: if it didn’t have the misfortune of being in the same key as the two better-known G-minor fugues, there’s a chance this one would be one of the “classics.” Not least because it does some of the same things as the other two. This moment when the feet abseil down the entire pedalboard could come straight from the “Great” G minor:

—as could any number of trio passages. The fugue subject is rhythmically distinctive and pretty catchy (almost string-style). And the ending is just what you hope for from a Bach fugue: more pyrotechnics. Even if the prelude wasn’t revised to foreshadow the fugue, all those thirty-second notes make the piece come around full circle regardless.

How Much is it OK to Add Change? Part III

Since I’ve already told one embarrassing story this week, I might as well get another confession out. My score of “Hilf, Gott” is full of corrections. As in, I tried my best to fix Bach’s mistakes.

Look, I know that sounds crazy or blasphemous, but have you heard this piece? Here’s a slowed-down, version that I tried to play as “straight” as possible:

Can you hear it? About 6 seconds in? The note in the left hand that has to be a mistake, right?

After a few hours of trying to make sense of this moment (and its repetition, and the equally weird one at 1:10 in this recording), I just crossed out the relevant sharps in a fit of optimism, hoping there might be some reason to doubt their authenticity.

Nope:

That’s about as explicitly spelled-out as it could be. If I’m getting rid of the sharp, I’m correcting Bach’s “error.” And one that seems to have been made very intentionally.

Honestly, it’s still tempting—the music sounds that weird. And it’s not a big change. But if something so strange seems to have been written on purpose, it’s probably best to try to make some kind of sense of it first. Even mistakes have motivations. This one, even if it borders on harmonic nonsense, can’t be a slip of the pen. So what’s going on?

With chorale preludes at least, we can always try to bail ourselves out by appealing to the text of the hymn. I usually resist this strategy—most pieces make some kind of musical sense by themselves, even if they might make a lot more sense once you know what they’re about—but it really does seem to help here:

Hilf, Gott, dass mir’s gelinge,

du edler Schöpfer mein,

die Silben reimweis zwinge

zu Lob den Ehren dein!

Help me, God, that I may succeed,

My precious creator,

In forcing these syllables to rhyme

To your praise and honor.

Ah. So the bizarre sharps, which stem from motivic repetitions in the left hand, can be seen as a kind of “forced” musical rhyme. Just as the canon between the two upper parts involves a lot of finagling (it switches intervals midway through, among other modifications). The music sounds contrived because that’s exactly the point. I’m not sure I love the result, but knowing the text makes it hard to justify modifying it.

Frankly, it was already pretty much impossible to justify the change: any time a musical moment is a) securely attributable to the composer, b) consistent, and c) sticks out like a sore thumb, you’re probably kind of ruining the piece if you uncork the wite-out. You might remember from Berlioz’s Memoirs (I’m aware that this is a preposterous way to begin a sentence) that François Habeneck edited Beethoven’s symphonies to redact “faulty” passages, passages which are almost inevitably the best parts. (Berlioz singles out the “ungrammatical” resolution of the clarinet’s famous held note in the second movement of Beethoven 5: it comes in at about 9:10 in this recording.) Nobody wants to be Habeneck.

But, to me, the moral of the story is definitely not “don’t change things.” Just be careful.

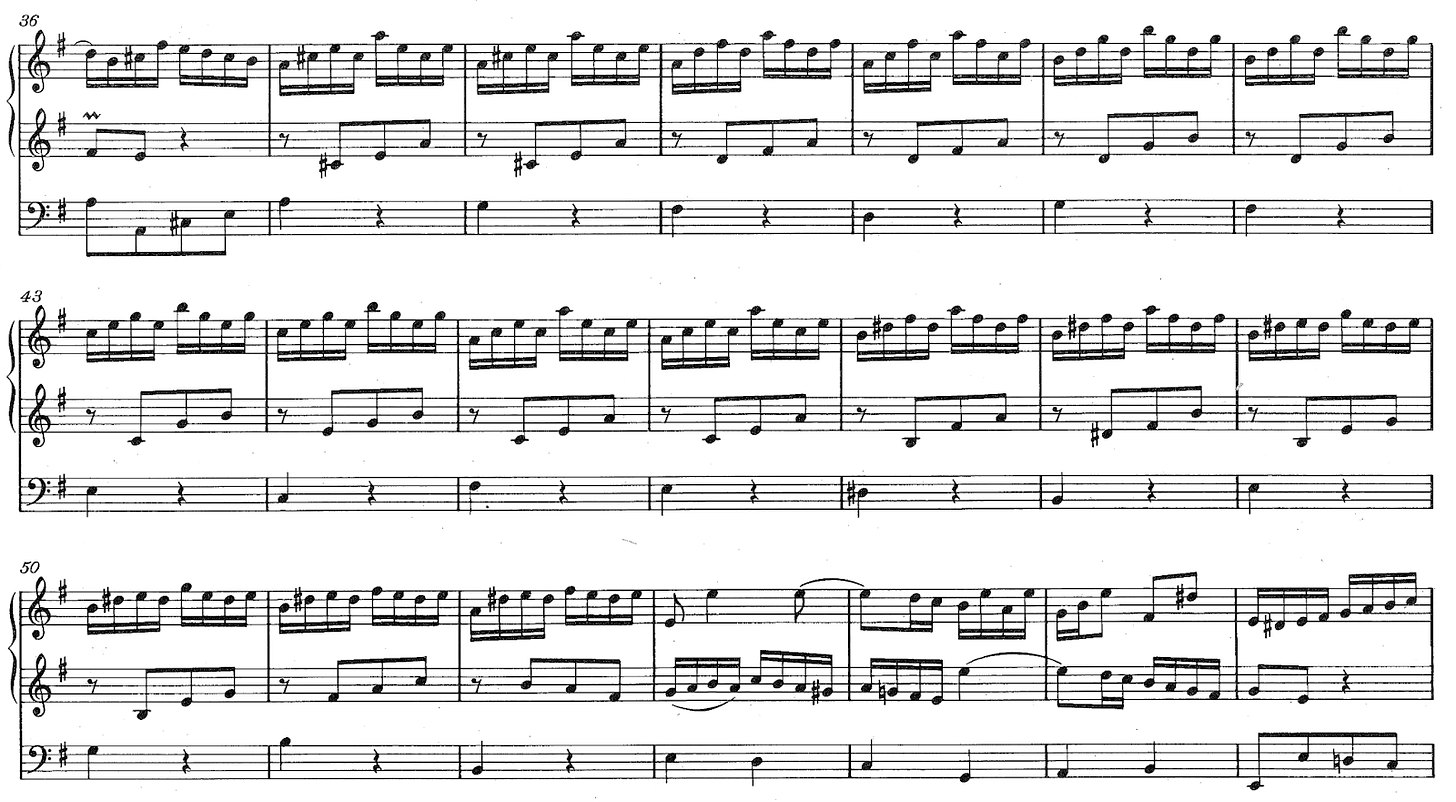

You’ve actually heard a number of deviations from the scores in this series so far. Take the last movement of the first trio sonata, where, even though Bach writes three B-naturals clear as day (second measure, right hand)—

—just about everybody wants to play B-flat for the last one. You can hear why. This is the piece as written:

And here’s the “corrected” version:

B-flat makes for a better descent to the follow A-flat, it avoids an implied augmented second, and it fits how Bach wrote it the second time around:

It’s important not to edit Bach to be as “consistent” as possible (after all, “quirky” is basically what the word “Baroque” means), but that seems like plenty of support for making the change. I don’t lose sleep over this one.

Similarly, see if you can tell what I “fixed” in this passage from the sixth Trio Sonata:

(It’s in the left hand, and makes things both smoother and a better match for a version of the same passage later in the movement. If you can’t tell what I changed, I count that as a point in favor of its acceptability.)

I don’t necessarily need analogous passages to feel good about making a change. Here’s a passage from the back half of today’s “Als Jesu Christ,” once as written and then with one accidental changed:

It goes by pretty fast (in the right hand, near the end), but I just find that the piece goes by a lot more smoothly with this change.

In some sense, when it’s not an incredibly consequential edit (like my proposed “corrections” to “Hilf, Gott”) fretting about changing one sharp or something else at that scale is honestly kind of missing the point. It’s not like this music existed in a fixed form; even in today’s post above, you’ve read about the earlier version of BWV 535 where the Prelude is basically a completely different piece. But even at a smaller scale sources for pieces like the “Great” G-minor fugue have all sorts of fun little discrepancies. Editors have to choose between them, but we shouldn’t just accept their decisions. With the “Great G-minor,” I tend to prefer the sources used by the old Bach-Gesellschaft edition, even if the “modern” Neue Bach-Ausgabe editors are correct that theirs are more securely attributable to Bach. A small example (BG first, then NBA):

To me, that “extra” eighth note really adds rhythmic juice and clarifies the counterpoint. I don’t really care how “authentic” its source transmission is.

More broadly, we know for a fact that Bach was constantly tinkering with both his music and that of others. Just like every other Baroque composer. And lots of changes and additions were expected: it would be downright weird to play the slow movement of an Italian violin concerto or sonata without “adding” a mess of ornaments. (You can hear me doing my best on Bach/Vivaldi here.) It’s perfectly in line with what we know of Bach’s performance practice to add a whole extra line to a piece. Andreas Staier (as usual) has the right idea. (Even if Max Reger might have gilded the lily a bit.)

In that context, what’s a couple accidentals between friends? No problem to make a couple changes. As long as we don’t Habeneck pieces like “Hilf, Gott.”

What I’m Listening To

The Messthetics and James Brandon Lewis – The Messthetics and James Brandon Lewis

Man, this album is a good time. As jazz fusion goes, it’s almost a little bit too catered to me: the “fusion”-ier tracks draw a whole lot on the kind of 2000s indie rock I’m a sucker for (tell me the guitar riff on “Fourth Wall” isn’t from In Rainbows), and I have to admit that I gravitated towards those first. “Emergence” rocks hard, and “That Thang” sounds sort of like if you told two-thirds of Fugazi (i.e. the Messthetics) to do their version of the “Hoe Down” from The Blues and Abstract Truth. Even opener “L’orso,” which started off sounding like one of those dreary jazz fusion grooves—“Hey, I just discovered the octatonic scale!”—quickly builds into something a lot more exciting.

It doesn’t hurt that the whole band sounds just fantastic. Anthony Pirog’s guitars, Brendan Canty’s drums, and Lewis’s sax in particular are just full of noises both punchy and subtle. They play together wonderfully—good tenor sax playing and heavily distorted guitar should always work in theory—and the marriage of styles produces some really fun rhythmic results. Lewis can sit absurdly far back in the pocket, and you can almost hear the Messthetics’ collective delight at how that plays against their (relatively straight) backings (“Railroad Tracks Home” has a great example). And when Pirog and Lewis get going at the same time (e.g. near the end of “Three Sisters”), the results are raucous and giddy.

Cyrille Dubois and Tristan Raës – Louis Beydts: Mélodies and Songs

A couple months ago, I “also liked” an album of songs by the obscure early 20th-century Italian composer Guido Alberto Fano. I was on the fence about giving that album a couple of paragraphs: I figured if I relegated it to “also liked,” then nobody would click the link—“Who is Fano and why do I care?” (I was right.) But I had very little to say about the songs beyond “These are very pretty, and a gazillion times better than you’d probably expect from an obscure contemporary of Puccini.”

Let me avoid making that mistake again. Louis Beydts seems to have been a more than capable composer of fin de siècle mélodies, and the song cycles here (Chansons pour les oiseaux seems to be best-known, but I was more impressed with Le Cœur inutile) are a decent expansion pack for the “later Fauré” universe. They may not be quite as memorable as Duparc at his best (to say nothing of Fauré himself), but they avoid Duparc’s occasional tendency to overwrite or steer toward the melodramatic. Dubois is doing great work here excavating and presenting this music. (The performances are excellent.)

Of course, I can’t in good conscience advocate for you to listen to an album of lesser-known fin de siècle song cycles without reminding you to listen to Lili Boulanger’s Clairières dans le ciel first. (If you’ve heard it before, you surely won’t refuse the invitation to listen again.) Unlike with Beydts, there are multiple recordings, even good ones, but the fact that no big name has touched this music is starting to verge on baffling. Significantly more ambitious than even La Chanson d’Ève, Clairières is the song cycle a composer like Ravel only wishes he could have written. Listen to it—Beydts can wait. (But do give him a chance. And Fano while you’re at it.)

Bolis Pupul – Letter to Yu

Look, I won’t say this is the absolute best album ever. A couple of tracks (e.g. “Doctor Says” and “Ma Tau Wai Road”) don’t really go anywhere, and frankly lack particularly interesting ideas to begin with. I’m not even sure if some of the tracks I do really like are necessarily all that good: “Frogs” is the kind of silly speech-song stomp I love, kind of like an LCD Soundsystem track in Cantonese. Its synth squelches kind of sound like frogs. Is that intentional? No clue, but it’s fun.

With all that out of the way: the best stuff on this album is great. “Kowloon” is a huge electropop bop, and “Spicy Crab” really brings the house down, in a weirdly haunted house kind of way. (Obligatory: it’s too spicy for your heart.) More subdued tracks can also work: “Completely Half” is a great entry in the depression-synthpop Pet Shop Boys lane, while the opening and closing tracks are beautiful and atmospheric. Sure, the concept and lyrics are really, really, really on the nose (track called “Cantonese” anyone? Literal letter to Pupul’s mother, Yu, read out loud in the title track?), but if you like that concept (or don’t care too much about lyrics), there’s a whole lot to like.

STAYC – “Fancy” (orig. TWICE)

Having written a lament for STAYC’s current musical direction, it might seem a little bit redundant to write about this song. And, honestly, it is redundant: this release just confirms everything I complained about there. I even (indirectly) contrasted “LIT” with the original “FANCY.”

Still, I think this cover is worth talking about because it gives one of the clearest illustrations I’ve seen of (K-)pop’s general musical direction over the past few years. Here we have one of the most musically successful production teams in K-pop (B.E.P.) completely butchering their own best song in the service of current trends. And they even gave us hints at their thought process, in the form of extensive behind-the-scenes content.

To start with the original—I guess I’m preempting the possibility of a fifth-anniversary post in a month—what makes “FANCY” so good?

Start with the harmonies: the verses of “FANCY” are based around one of those tonally ambiguous chord loops that you never want to end, but instead of something hackneyed like vi-IV-I-V (to be clear: a lot of my best friends are vi-IV-I-V songs), they landed on the much fresher vi-V-I-ii. But they’re not stuck on it: instead, the prechorus switches to the even more unusual I-V4/2/IV-IV-V, and the chorus flips the verse’s chords around to give the endlessly repeatable IV=ii-V-I-vi. That symmetry pays dividends, since both the verse and chorus make sense in C minor as well as E-flat major: the verses start out sounding minor and end in an ambiguous major, while the chorus starts out sounding major and ends in an ambiguous minor. The tension between tonic and relative minor adds a lot to the song’s slightly yearning feel, and it’s perched on an absolute knife’s edge: to counterbalance the tonally unambiguous prechoruses, the bridge is definitively in C minor, albeit with a relatively weak minor dominant.

The version B.E.P. cooked up for STAYC (“Fancy” without allcaps) is almost like if the bridge of “FANCY” were the whole song, harmonically speaking. Instead of those carefully balanced, addictive chord loops, almost the entire song uses an unrelenting and drab iv-v-i progression. Not only does that get rid of all the tonal ambiguity, the harmonic drama that plays out between verse and chorus in “FANCY”: it’s also literally all minor, like a greyscale version of the original chords. (Although, ironically, the new harmonization of the bridge is a welcome respite.)

How about “FANCY”’s hooks? Obviously there are the “tropical” pitch-shifted vocals that open the song and provide little hits throughout: having that opening hook come back for the second verse (0:28) is just genius. Then there are the synths in the chorus: the midrange countermelody at around 0:58 and that steelpan-like bounce starting at 1:12 (hearing a scale-degree 3 pedal held over IV-V-I-vi would surely bring a tear to Chopin’s eye). Even the synth bass is constantly roaming around. It’s all intensely melodic, rhythmically interesting, and sonically varied. The whole song just pops.

“Fancy” gets rid of literally all of that. There’s still some swirling action in the guitars, and an insistent beeping that, for better or for worse, will probably conjure up the trumpet loop from “ETA.” There’s a ton going on, especially in the beat, but not much of it really grabs you.

How about the tunes? That part hasn’t changed, but the character in which they’re sung sure has. “FANCY,” as the opening line literally tells you, is trying its best to be “tropical,” so its rhythms are dominated by variants of tresillo rhythms: 3+3+2 in the verses, 3+3+3+3+2+2 in the chorus. There are delightful syncopations throughout (starting from the opening hook), including of those tresillo rhythms themselves. Nayeon’s “ana / Hey I love you” (1:01—I never said the lyrics are great!) starts out sounding like a slow 3+3+3+3+2+2, but short-circuits after the third 3 in a creative and original rhythmic touch. (3+3+3+1+2, thus feeling like a syncopated 3+3+2+2). Tzuyu’s “Jeo byeol, jeo byeol…” (0:54), on the other hand, overshoots the fast double tresillo, giving 3+3+3+3+3+3 (!) before breaking back into duple subdivisions. The result is an incredible sense of rhythmic tension and drive, of melodic moments that sound like they’re pouring out uncontrollably.

“Fancy” does actually keep all of that, although Seeun’s “Jeo byeol…” (0:45) rationalizes the rhythms a bit. But the way it’s all sung is completely different. The song is transposed down a minor third, so that the high note in the chorus is now a comfortable C5, as opposed to the E♭5s that dominate the chorus of “FANCY.” I know that Nayeon and Jihyo’s somewhat pinched tone in that register bothers some people, but the high notes do have a purpose: they give a feeling of energy and intensity that perfectly matches the song’s melodic and rhythmic profile. Without them, the song not only sounds a bit flat, but also feels weirdly mismatched. Why all this rhythmic activity (in the instrumentals) and energy (in the tunes) if it’s going to be sung like this?

And, conveniently, we know exactly the vocal tone that B.E.P. requested for this song; you can hear them talk about the recording process starting about 11 minutes into this video (and especially around 13:00):

As they say, Isa and Yoon found it hard to try singing with such little support. In the actual recording behind-the-scenes video, Yoon even says

—which matches the “listening in bed” vibes Isa mentioned. I guess that answers this:

(I would prefer not to know the real answer.)

The irony, of course, is that STAYC has significantly better singers than TWICE. That’s one of the big parts of their appeal: all six are very good, and they like to show it live. It’s even more of a shame to hear them sing like this when you know what they can do.

And really, that’s the biggest problem with “Fancy.” By itself, it’s actually not half bad, and definitely a step up from “LIT”: all that beeping, chugging, and burbling rhythmic activity in the beats is pretty fun, the tunes are still great (even when the harmonies have been butchered like this), and I do really like the new harmonization of the bridge. I also just like STAYC a lot more than TWICE in general (sorry!), both as singers and as personalities. But if you know the original—and if you’ve heard just about any K-pop at all, you’ve heard “FANCY”—it’s impossible not to miss all of the stuff that makes TWICE’s song tick.

Luckily, STAYC change musical directions often enough that this phase will hopefully be over somewhat soon. And maybe that will signal the beginning of the end for this entire godforsaken era of bland, sleepy, “Y2K”-esque music. Bring back music like “FANCY.” Just not in the form of “Fancy.”

Also liked…

MUSM – MUSM op.6

Kahil El’Zabar’s Ethnic Heritage Ensemble – Open Me, A Higher Consciousness of Sound and Spirit

Amir Amiri and Infusion Baroque – East is East

Yard Act – Where’s My Utopia?

Amirtha Kidambi and Elder Ones – New Monuments

Third Coast Percussion – Between Breaths

Kacey Musgraves – Deeper Well

What I’m Reading

When I ran across Damion Searls’ new translation of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus at the Sem Co-op, my immediate instinct was to pull up Jonathan Egid’s TLS review of two new Tractatus translations to see which one this was. How foolish I was—Searls’ is neither. In other words: having been stuck with one bad translation (and its revision) for decades, we now have four versions to pick from. I decided it wasn’t going to be worth agonizing over which one to buy and picked up Searls blind. Marjorie Perloff wrote the introduction—how bad could it be?

I’ll confess that, as much as I love later Wittgenstein, I’d never actually gone through the Tractatus before, so I couldn’t tell you how much better this version is on the level of the whole text. But it’s definitely way easier to read at the level of the sentence. Searls makes a very loud point in his introduction of explaining how much he is Anglicizing his translation (changing German nominals to English verbs, rearranging sentences), and it’s undeniable that the result is about as fluent of a read as it could possibly be.

In some ways too fluent: Searls doesn’t tell you this, but he repeatedly inserts glosses into his translation, typically in the form of parentheticals. I think they’re philosophically harmless—he’s usually reminding you of a word’s narrow meaning as established by a prior use—but it can sometimes feel a little bit invasive, or even patronizing. Same with some of his efforts to indicate when Wittgenstein’s terminological usage is “unusual” or “metaphorical” by the use of scarequotes. That really gets him into trouble when he starts scarequoting Wittgenstein’s use of logical “space” (Raum) and “place” (Ort). Sure, those are metaphors, and maybe Searls is even correct that they’re more natural in German—but they’re also obviously derived from the language of topology, and surely need no scarequotes. (Knowing this would also have allowed him to use the much more apt “locus” instead of “place”—an Ort can be distributed rather than contiguous, and it’s defined in relation to a function or similar object.)

At the same time, well, this text is a whole lot less transparent than Searls or Perloff would like you to believe. I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s true of the introductions for all three new translations: presumably, everybody wants to tell the reader that they’ve finally made this text readable. And, if you really want to sell copy (Norton surely does), you’ll solemnly tell everybody that this is a literary text, even poetic.

It’s mostly not. Forget about the logical notation (if Searls or Perloff were really interested in guiding first-time readers through the text, they’d at least point us to the early propositions of §5, where the symbols are all explained): this is, after all, a book on the limits of logic and philosophy, and its core (especially the later parts of §5) are pretty tough sledding. There’s no reason to sugarcoat it: that stuff is just deadly boring unless you really care about logic.

Luckily, there’s plenty more to the book (even if the famous stuff really is all from the beginning and the end). It may not be as chatty or poetic as later Wittgenstein can be, but it’s still the same anxious, egotistical, wannabe mystic writing the book: it’s absolutely delightful when Wittgenstein interrupts §5.54 (on propositional logic) to explain that psychology’s conception of the soul (Seele) is all wrong. I’m glad to have finally read the Tractatus, and Searls definitely helped. Even if—to be fair—the other two translations probably would too. Just pick up whichever you happen to see first; anything’s better than Ogden/Richards.

A few others:

Nature Communications – Timbral effects on consonance disentangle psychoacoustic mechanisms and suggest perceptual origins for musical scales

NY Times – The Tren Maya Is Opening Up the Yucatán, for Better or Worse

Apollo – The making of the Monet myth

Harper’s – Children for Sale

Hakai – The Eider Keepers

Pedestrian Observations – Trains on the Moon

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

Although one of this piece’s closest comps is a movement from Kuhnau’s first Biblical Sonata.

yeah...that K pop cover is just weird...

....W would have liked topology of he had known anything about it...I think it is the best way to read 'topos' in Aristotle...