BWV 847, 871 – Preludes & Fugues in C minor from The Well-Tempered Clavier

Plus: Binchois for the whole family, fromis_9's H1-KEY summer, Yasunari Kawabata's WWII novel, and more!

Ishkōdé Records have done it again. Having brought us Sebastian Gaskin and Digging Roots and Aysanabee,1 they’ve now delivered Brought To You By Tragedy, the fabulous debut EP from Anishinaabe singer-songwriter Thea May. (I’m sure I’ll get to the rest of their roster in short order.) As with their other releases, this is big, spacious, generously produced music, an extremely solid alt-rock album full of great builds and great guitar work. And as usual, it’s highly personal, although this time perhaps the diaristic plainness of lyrics like “This is the trauma shit, we laugh or we let it win” from, um, “Fuck You for Dying” is a bit more direct than you might have bargained for. As Ishkōdé put it, “Don’t bother with anything but honesty with Thea May. An emo kid at heart….” You don’t say.

Still, Brought To You By Tragedy does also represent a bit of a departure. There’s basically no gesture toward overt “Nativeness” anywhere on the album: no lyrical references to medicine or even long hair and certainly no evocations of “powwow-style” singing or drumming or flute-playing. Her bio evokes the usual stuff about “finding purpose” and “baring her soul” without drawing any further link to heritage or the like. Hell, even the namesake Tragedy of the album is characterized in purely personal terms, not generalized as it so easily could be.

I think this is an unambiguously good thing. Certainly for May, who is not being forced to shoehorn her story into any particular template or slather it with a potentially dishonest cultural patina for the sake of marketing. And it’s also a relief to see an Ishkōdé release that’s comfortable telling a Native story without making it into a Native Story. Not that they should stop doing that per se, but it’s important to make room for stories (and tragedies) at all scales. Sometimes a straightforward rock album is just the ticket, with no need for additional window-dressing, no matter the artist or the label. Brought To You by Tragedy is great just as it is. You can hear May talk more about her work here, here, and on her Youtube channel.

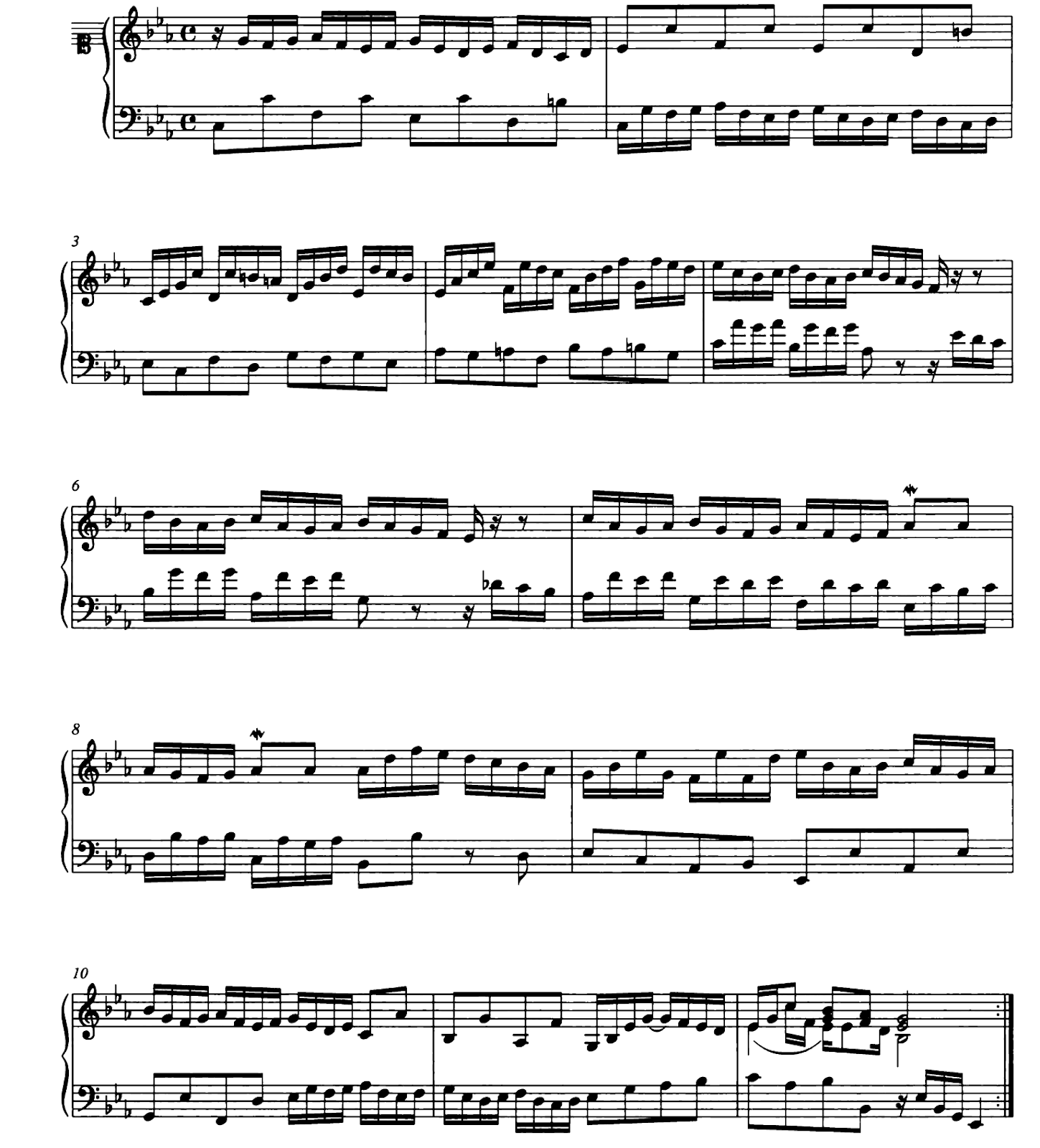

BWV 847, 871 – Preludes & Fugues in C minor from The Well-Tempered Clavier

Book I

Book II

They even kind of look the same. Where Bach seems to have made sure that his C-major Preludes and Fugues come across as manifestly or even programmatically different pieces, their C-minor counterparts do much less to overtly distinguish themselves. Consider:

vs.

or

vs.

I’ve left these snippets unlabelled to make a point: at least in terms of superficial figuration and texture, there’s not a lot of daylight between these preludes. (I put Book I first each time.)

Those commonalities—all that shared basic musical material—makes it all the more remarkable that these two preludes in fact are quite different, drawing on completely opposed forms and techniques.

To be fair, I’ve been cherrypicking quite heavily to make the two look so similar. Zoom out and the two preludes don’t look much alike at all. Here’s the first page of each:

and

I’ve given you this sudden barrage of sheet music to make a couple points. First, you can see that the relationship between the hands is quite different in each piece. In Book I, the left hand mirrors the right for almost the entire time, creating a completely homogeneous texture. By contrast, in Book II, the left hand and right hand trade off “melodic” and “accompanimental” parts in different rhythmic values. Both of these preludes are in two parts throughout, but only the Book II prelude sounds like a two-part Invention.

There’s also, well, a lot more invention throughout the Book II prelude. Book I’s is almost completely uniform, relentlessly using the same figure to elaborate on a simple chord progression. (In this, it’s just like the famous C-major prelude, and it even has the same subtle shifts of strong and weak measures—I won’t subject you to a blow-by-blow account of those shifts this time, but hopefully my interpretation is audible in the recording.) Book II, meanwhile, constantly changes it up, using each version of its basic figure for two measures at a time before switching to another. Book II, as you can see, also has significantly more variety of texture: the bass sometimes drops out as the left hand leaps to a high position, and there are judiciously placed ornaments and rests, cracks of light where the texture thins out to a single voice. Book I, at least until late in the prelude, is just a constant sea of black: uninterrupted sixteenth notes in both hands.

“Until late in the prelude”: if Book II is more varied than Book I for most of the piece, the earlier prelude has its revenge toward the end. About a minute in (0:57), the Book I prelude suddenly drops down a single voice, extending a long dominant pedal that leads to a giddy cadenza and then a lavishly ornamented adagio. If I’d given you the second pages of each prelude, you’d have a very different impression of the contrast between them. How’s this for variety?

Leaving aside which page I chose, the biggest reason to give a full page of each prelude in the first place is to illustrate the different forms of the two pieces. You may have noticed the repeat sign at the end of Book II’s page 1. Pop quiz: how many repeat signs do you remember seeing in all of The Well-Tempered Clavier Book I?2

Here the differences between these two pieces can stand in for the gap between all of Book I and all of Book II. The Book I C-minor prelude, with its thoroughgoing exploration of a single kind of figuration and even with its cadenza at the end, is entirely representative of the Book I preludes in general. The binary dance form of Book II’s C-minor prelude, on the other hand, is eminently typical of Book II as a whole. I doubt that Bach really intended to showcase his ability to construct two such opposing prototypes out of the same building blocks—to be honest, I think this musical figure just came naturally for him in C minor—but he might not have been able to do much better if he’d tried.

The fugues are equally distinct, although again in ways that aren’t necessarily easy to hear. The Book I C-minor fugue is the classic example of a “permutation” fugue, one which pits its subject (highlighted in red) against two countersubjects (green and blue) in, well, most of the possible permutations:

It’s a three-voice fugue with three subjects, so for each position of the fugue subject (soprano, alto, or bass), you have two possible ways to configure the other voices: here, with the subject in the bass, countersubject 1 could be in either the soprano or the alto, and countersubject 2 could correspondingly be in the alto or the soprano. That makes for six total possibilities. Bach is less fastidious than he’s sometimes been made out to be: this fugue only uses five of the six. (Knock yourself out—or drive yourself crazy—trying to figure out the missing one.)

Instead, most of the fun of the Book I C-minor fugue lies not in the exhaustivity of its fugal entrances but in the episodes between them, the lengthy passages where Bach chops up, extends, flips, and otherwise toys with each of these subjects. A lot has been made of these episodes (this must be the most analyzed fugue ever written), especially about how several of them recur symmetrically in each half of the piece, but I think the more important takeaway is how Bach can extend the spirit of “permutation” to these seemingly “freer” passages. Consider the two short episodes here (starting at 2:08) surrounding the fugal entrance in mm.11–12:

Mm.13–14 especially might not look like much of anything, basically a series of scales going in different directions at two different speeds. But those scales are clearly derived from parts of countersubject 1 (in green above), now unspooled at greater length and made to play against itself. Similarly, mm.9–10 consist of parts of the main subject played against itself while another derivative of countersubject 1 hums along in the bass. And of course the two episodes sound like mirror images of one another, one with the sixteenth notes heading downstairs in the bass and the other with them flying up to the top of the keyboard. There are far more than six combinatorial possibilities in this music.

If the Book I fugue is all about how different subjects can be configured and played off one another, then the Book II C-minor fugue is all about the different ways the same subject can play off itself. That is, it’s all about stretti, not permutations.3

Actually, this fugue doesn’t sound like it’s “about” much of anything at the beginning. The most interesting events of the first page are how the fugue subject is stretched out of shape. Here it is, first in the bass, and then with a new rhythm (and partially distributed over two voices) in the right hand a measure later (3:07):

And here it is again, bent nearly out of recognition in the left hand (3:21):

First you hear the subject normally in the left hand (beginning in m. 11, but you can recognize the two sixteenths at its tail end here). But what follows is one of Bach’s most daring exercises in octave equivalence. The notes of the subject’s next entrance should be “C-B♭-C D-G-C-B♭-A B♭,” and all of those notes except for the first duly appear. But the D is supposed to be a step above the preceding C, not a seventh below; and the next C is supposed to be in the same octave as the first. Bizarrely, there’s no particular reason for Bach to have distorted the subject in this way: the hands wouldn’t clash at all, for instance. He’s just having fun.

As strange as this treatment is, it does nothing to prepare us for the second half of the fugue. Now the rhythmic and pitch distortions completely disappear, to be replaced by a host of other contrapuntal tricks (3:30):

Now the fugue subject retains its recognizable rhythmic shape and melodic contour, but you hear it first twice as slow (those quarter notes in the alto) and then upside down (in the bass). By the end of this line, it’s also interrupting itself midway through: the first stretto of this stretto fugue. Also, the fugue switches from three voices to four.

I’ll spare you the details of what follows, but I can’t resist quoting the final stretto, where the entrances of the subject pile up on each other after as little as a quarter note’s interval (4:03):

The Book I C-minor prelude may have its counterpart beat when it comes to climactic finales, but here it’s surely Book II that takes the prize. I like that symmetry, unintentional though it might be. Once you listen past the similarities, these Preludes and Fugues have divergent and complementary delights.

What I’m Listening To

Baptiste Romain and Le Miroir de Musique – Gilles Binchois: Loyal Souvenir

I never quite got Binchois. Keep in mind that my love for composers of the fifteenth century runs quite deep, perhaps excessively so: I’m happy as a clam with relative no-names like Pullois and Prioris and Faugues. (I wrote about Faugues for my PhD application.) But Binchois? Never saw the appeal. Which is a bit of a problem given that, at least according to the writers of his time, Binchois was second only to Guillaume Du Fay among Continental composers. If you take a music history class or read a textbook, you’ll duly see the early 15th century listed as something like the “Age of Du Fay and Binchois.” Blegh. Give me one of the composers named De Lantins instead.

Part of my problem probably comes from the canon. Binchois’ big-name songs like “Deuil angoisseux” and “De plus en plus” are just too monochromatic for me, too sickly sweet, revelling too much in the new “English” vocabulary of constant thirds and sixths. They’re also too relentlessly “major”-sounding, too limited in their harmonic ambit. “Triste plaisir” (my favorite?) and “Adieu mes tres belles amours” provide a bit more variety, but a whole album of Binchois chansons has always been too much for me. (The ABaAabAB repetitions of the rondeau form don’t help.)

It turns out that what I needed was in fact precisely just a Binchois album that’s not all chansons. Not that his sacred music is a “revelation” exactly: there’s a lot of extremely rote writing in some of these motets (all that fauxbourdon in “Salve sancta parens”!), and none of the mass movements have the ambition of anything in the big Dufay cycles. At best you could say that these pieces are somewhat more conservative than the chansons. There’s a reason it took until 1992 for Binchois’ sacred music to be fully edited and published.

But by interspersing the album with this music—and indeed, framing it with a Sanctus and an Agnus Dei—Baptiste Romain and his group have finally succeeded in giving a version of Binchois I can really love. Partly, to be sure, because I don’t mind “extremely rote” polyphony from this period in the slightest. But mostly because it gives a more three-dimensional portrait of the composer, an album that doesn’t have to rely solely on changing up the instrumentation to break up the monotony.

Le Miroir de Musique also do a lot with instrumentation, and I’m sure there are reasons to quibble with some of their choices (e.g. the always-controversial use of instruments for cantus firmus tenors in motets like “Veneremur Virginem”). I’m also sure that some of the more up-to-date performers of fifteenth-century music would say that the tempi drag, that the singing style is a bit too “cathedral-y,” that the sound in general reflects more the canons of “modern early music” than what we know about performance in Binchois’ time. It may well, and I do indeed wish they’d pushed several of these tempos and gone with a slightly more wiry and less “choral” vocal sound. But those are fairly minor points. For what they are, the singing and playing sound lovely. And they produced a Binchois album that I feel like I can recommend without reservation. Even if—or maybe because—“Deuil angoisseux” and “De plus en plus” didn’t make the cut.

Folkatomik – Polaris

Another somewhat delayed listen courtesy of World Music Central, this one even better than the last. Or at least more entertaining (no funeral songs this time). In a just world, this would be what Eurovision sounds like: Southern Italian pizzica folk music over a disco beat. Like Eurovision, the result might be a little goofy, but unlike the vast majority of what comes out of the Song Contest, this music uniformly rules. It’s extremely hard not to get up and dance while listening to Polaris.

I’ve simplified a bit. If you listen to the album or click through to that review, you’ll find a veritable fritto misto of influences, from Latin percussion to “wind instruments from Arab, Turkish, Andean, Irish, and Sicilian traditions” and lots of little electronic blips and boops. Far from being a simple “update” of Italian folk music, Polaris is a real World Music album.

Then again, Southern Italian music was always World Music. The fusion of influences from West Asia, Turkey, North Africa, Spain, and even Celtic lands makes complete sense for an area that went from Byzantine to Arab to Norman to Spanish before becoming “Italian.” Is it stretching things too much to point out that the founders of Italo disco were also born in Sicily? (Yes, it is.)

In any case, despite the whirl of global sounds, Polaris’s core sonic identity remains remarkably consistent. Most of the tracks are in fact actual folksongs, and if you stripped away the production and a couple details of arrangement (or structural rearrangement), I think many of them aren’t too far from how they’d be performed in a “straight-up” context. The mandolin playing, drumming, and singing is all fabulous too. It’s everything we love about Orange Caramel and more. Dance away.

Skunk Anansie – The Painful Truth

There are few better symbols of the disconnect between the U.S. and U.K. music scenes than Skunk Anansie. In the U.K. they were Glastonbury headliners, both popular enough to go platinum with multiple albums and cool enough for Björk to debut “Army of Me” on TV with them. Skunk’s Spotify plays from Stoosh alone easily surpass 100 million. But in the U.S. they might as well not exist; not a single charting album or single and basically no profile. Even as comeback albums from The Cure and Stereolab have gotten breathless reviews in all the usual outlets, The Painful Truth—Skunk’s first album in a decade—dropped to dead silence on this side of the Atlantic.

Truth be told, I might have said “you’re not missing much” before this release. I have no great affection for Skunk’s big hits: “Hedonism” does absolutely nothing for me, while “Charlie Big Potato” is…perfectly good? Unexceptional? Skunk’s discography can sound both histrionic and strangely empty; their releases from the 2000s are more consistent but less characterful. I’m sure the live shows have always been great but it would be hard to say the same about the songs.

Luckily, unlike those comeback albums from The Cure and Stereolab—where the best praise anybody seemed able to muster was “It’s about as good as their old stuff!”—I actually think The Painful Truth is Skunk’s best album by a very wide margin. That probably means actual fans hear it as a kind of betrayal, but luckily there are basically no actual fans to be had in this country. Maybe the big pop gestures of “Cheers” and “Animal” sound like selling out to them. Maybe I’m supposed to think that opener “An Artist is an Artist” passes from throwback to pastiche, or that “My Greatest Moment” is too atmospheric 2010s pop for a band known for pushing “clit-rock, an amalgam of heavy metal and black feminist rage.”

Or maybe those are just straw men. Because—and this is something Skunk always had—the sheer bravura of their performances absolutely carry the songs. By drawing the album on this grand scale, Skunk and their producers have finally created a canvas big enough for Skin’s vocal heroics to be fully actualized. The synthpop backings of “This Is Not Your Life” might be a serious change of pace from their previous music, but Skunk sound right at home delivering them. It’s a great song on an album full of them.

fromis_9 – From Our 20's

H1-KEY – Lovestruck

Summer is saved, and frankly so is the year as a whole. It’s been a fairly down year for K-pop to date, but fromis and H1-KEY are back with two blockbuster releases that simply exude summer fun.

My rhetoric here might sound familiar or even repetitive, since I praised KickFlip’s new release in similar terms last month. The similarities go deeper still, since both of these albums pick up on the same trends that KickFlip exemplified. “Anime OST” sounds, pop-punk revival, power pop, and all the rest are very much on display. Consider:

Where KickFlip had “Complicated!!” on an album that rips off Blink-182, H1-KEY now open their album with “Good for U,” a song that wears its jilted-lover Olivia Rodrigo influences on its sleeve. (“Good for U” uses a rotated version of the chord progression from the chorus of “Good 4 U.”)

Yes, K-pop copycats continue to eschew subtlety in their titles: Jeongyeon’s take on the stomp-clap-hey country of “Tipsy” is literally called “FIX A DRINK.”

For their part, fromis give us their own version of Avril or Olivia with “Love=Disaster”: you can almost hear this song as a remake of “get him back!” with some vocal effects from the chorus of “obsessed.”

Back to H1-KEY, whose title track “Summer Was You” has backings that could easily pass for an Ado song, and whose closer “Let Me Be Your Sea” resembles the lush, Disneyfied J-pop of Nogizaka46 almost as much as it matches K-pop predecessors like 2011 IU.

For that matter, I can hear the suave disco-funk stylings of fromis’s “Strawberry Mimosa” as a fashionable nod to city pop. And “Love=Disaster” has a whiff of J-rock in its production to boot.

Yes, both groups can be trendy in bad ways too. “Strawberry Mimosa” and H1-Key’s “One, Two, Three, Four” are the same midtempo blah imitation R&B that’s been pervasive in K-pop ever since the success of “Say So” and its Korean derivative “Cupid.”

“Strawberry Mimosa” even has cutesy sing-talk to drive the point home. It also succumbs to a different trend with the vaguely ILLIT-style repetitions of the chorus.

That’s a lot of words calling these albums trendy or even derivative. I’d rather have started with the positives, but it’s frankly much more difficult to express what makes these albums so great. In generalities, it’s not hard: the best of these songs (“Good For U” and five out of six songs on the fromis album) are high-energy, ultra-catchy, strongly-etched melodically, and well-matched to each group’s image. In trying to be more specific, I’m not sure I can do a better job than the songs themselves do. I’ll do my best, but I suspect that—as always with the best songs—this music will always remain its own best advocate.

A surprising commonality between H1-KEY and the reconstituted five-member version of fromis_9 is great singing. These releases really lean on that strength, in each case pushing the whole group’s voices to the limit. Yel from H1-KEY rightly notes in this interview that almost the entire Lovestruck album is higher-pitched than basically any other H1-KEY release to date. (Not coincidentally, the last H1-KEY album that I loved this much was 2022’s literally “high-key” record RUN.) From Our 20’s is even more extreme in this regard, constantly having Jiwon and Hayoung belt out at the top of their ranges, giving climactic choruses to even late-album B-sides like “Twisted Love.” They also sing together far more than I’ve ever heard on a fromis album: the choruses of “LIKE YOU BETTER,” “REBELUTIONAL” and closer “Merry Go Round” are full of juicy harmonies and forceful unisons. I should also say that none of the singing on either of these albums sounds remotely like J-pop.

Also unlike J-pop is the careful balance of simplicity and complexity in the rhythms and harmonies of both albums. One of the reasons that “Good For U” and “Summer Was You” don’t quite sound like literal anime intros is that they stick to relatively straightforward chord loops or progressions throughout, eschewing the incessant applied chords and chord extensions that muddy up so much J-pop. On fromis’s album, “REBELUTIONAL” and “Merry Go Round” actually do engage in a fair bit of chromatic harmony—this is part of why they don’t sound much like current Billboard Hot 100 stuff—but dosed out carefully and at a slow enough pace to actually make an impact. In both songs, the clear-cut melodic rhythms of the chorus are also well-calibrated to emphasize and gain strength from these chords. This alignment of harmony and rhythm is part of what makes the tune at “Like merry go round, yeah” so unforgettable.

There’s one thing that neither H1-KEY nor fromis (nor indeed KickFlip) pull off on these releases: this music isn’t cool. Much the opposite: the lyrics (and some aspects of the production) can be downright silly. Conspicuous clichés like “So hit it off, one, two, three, four, dive” (groan) and “L-O-V-E…A to Z” on “LIKE YOU BETTER” and “REBELUTIONAL” are bad enough before you consider that the latter is literally called “REBELUTIONAL.” Merry go rounds have been cute and good vocal showcases in K-pops before, but they’ve never been cool. For that matter, the lyrical attitude of “Good For U”—just as in “Good 4 U”—is the opposite of cool. This is not a song about being “over it.”

Maybe nothing is cool anymore, and the postwar window where “cool” made sense as a cultural category has fully closed. Olivia Rodrigo isn’t cool and she knows it. Billie Eilish’s whole thing is being uncool; the correspondingly popular male stars are so uncool that it’s not even worth mentioning them here. (Do the names Myles Smith and Alex Warren do anything for you?) But K-pop hasn’t quite gotten the memo. New groups are still trying their best, as with the fine but repetitious debut from ALLDAY PROJECT. Older groups like aespa are trying to recapture their cool to disastrous effect. (But don’t they realize that “SAVAGE” was always kind of ridiculous?) I never really liked ENHYPEN, but the cargo-cult cool of “Outside” has to be a low point.

But when has pop music ever really been cool? I mean real Pop, narrowly defined to exclude rock gods and hip-hop moguls, neither of whom can really exist in the industrial ecosystem of K-pop anyway (although BIGBANG came reasonably close). How could that even be possible when making earnest, summery anthems for teenagers? If the song is good enough, who cares?

In other words: I think the creative teams behind fromis and H1-KEY (and KickFlip) have understood the assignment. There is something pretty goofy about those belted choruses to “Merry Go Round” and “Twisted Love,” to the sincerity of “Good For You” and the silly little choreography that goes with it. It doesn’t matter in the least. I don’t expect or even really want cool from pop music. Just give me songs like these and I’ll happily scream “REBELUUUUUTIONAL” as much as you want.

Also liked…

Marie-Elisabeth Hecker and Martin Helmchen – From Eastern Europe

Duo Ruut – Ilmateade

Hayden Pedigo – I’ll Be Waving As You Drive Away

José de los Camarones – Aventuremos la Vida

El Pantorillas – Palomo cojo

Little Simz – Lotus

Loyle Carner – hopefully !

What I’m Reading

It’s something of a mystery to me, and deeply disappointing, that the recent English translation and publication of Yasunari Kawabata’s The Rainbow wasn’t more of a literary Event. It’s a major work from East Asia’s first Nobel laureate in literature and one of Japan’s canonical masters of prose style. It’s one of Kawabata’s longest and most ambitious novels, from the same period as his acknowledged masterpieces (right between The Sound of the Mountain and The Master of Go). Why wasn’t everybody talking about it? How did it go unreviewed in almost every literary journal and book review section?

For that matter, the same characteristics make it equally mysterious that The Rainbow would have remained untranslated for so long. Snow Country and Thousand Cranes were both available in English within a decade of their publication; the later novels followed soon after Kawabata’s Nobel win in 1968. His only other works that have waited this long are juvenilia and his unfinished/posthumous final novel. It’s also not as if Kawabata published all that much: he’s not like Tanizaki or Mishima, prolific authors whose back catalogue can always be scoured further to yield yet another new translation for the English-language market.

My only plausible explanation for the second mystery makes the first one all the more infuriating. I have to think that The Rainbow wasn’t allowed to be published, that somebody—Kawabata, his publishers, his translators—thought that the subject matter simply wouldn’t go over well. Because The Rainbow is a novel about World War II.

In some sense that shouldn’t be surprising, and indeed all of Japan’s great postwar fiction is in some way about the war. But I can’t emphasize enough how rare it is to see a novelist who was an adult during the ‘30s and ‘40s fully and explicitly delve into the war’s psychology and aftermath. There’s the military fiction of Shohei Ooka, the sentimental propaganda of Masuji Ibuse, and Shusaku Endo’s horrifying POW novel The Sea and Poison; and then later there’s Kenzaburo Oe’s (born 1935) early political fiction. But Mishima, Tanizaki, Osamu Dazai, Fumiko Enchi—Japan’s major literary voices of the 1940s, to the best of my knowledge, left the war out of their fiction entirely. I thought Kawabata had too.

Instead, the characters of The Rainbow frankly discuss the impact of firebombings, the continuing threat of nuclear weapons, impending war in Korea, and the lasting scars of those who were close to Japan’s troops. Most extraordinarily, about halfway through the novel we encounter the (presumed) kamikaze pilot Keita in his last moments before being sent off to the front, and much of the novel’s second half is devoted to processing what Keita’s life and death meant for his family.

It’s Keita’s lover Momoko who emerges as The Rainbow’s protagonist. By the time we meet Keita in the mid-novel flashback, we’ve already been made acutely aware of Momoko’s own death drive, inherited from her mother and reflected as well in her new lover Takemiya. Maybe I’m overreading and trying to turn this book into something like The Tin Drum, but by linking Keita’s military fate with Momoko’s civilian suicidal tendencies, Kawabata seems to be making some kind of commentary on at least one strand of fascist Japan’s national character. Under that reading, Momoko’s half-sister Asako would represent a younger, more naïve Japan that’s determined to uncover and confront the secrets of the past (as represented by their other half-sister Wakako). Asako falls gravely ill and progressively drops out of the novel’s action, and the attempt to reconnect with Wakako is an unmitigated disaster; I’m not entirely sure what that was meant to say about Japan’s future. (Asako is also the sister who consistently chases rainbows, seemingly as a double symbol of hope and connection to the spirit realm.)

I’ve only scratched the surface of The Rainbow’s themes and intricacies—the sisters’ father is an architect, and lasting symbols of Japan’s past feature prominently throughout—but you can already get some sense of its emotional heft, its unusual (for Kawabata) intensity. The writing, I think, is up to his usual standard as well. I say “I think” because Haydn Trowell’s somewhat tin-eared translation does Kawabata no favors. I get that I’m implicitly comparing Trowell to the prose of literally Edward Seidensticker—who probably deserves some credit for winning Kawabata the Nobel—and nobody will come off particularly well under such scrutiny. But seriously: Trowell really seems not to care about rhythm at all, and his didactic in-text explanations of Japanese cultural forms give off the odor of a school reader or the world’s worst New York Times profile. If you think I’m exaggerating, just know that he uses “honorable face,” “honorable beans,” and “honorable bamboo shoots” italics and all, to translate what I assume is a series of obsequious prefixations using お-. If The Rainbow is your first Kawabata, you’ll simply have to believe me that his writing does not usually sound ridiculous.

If you still need it, I have one final enticement. In the first chapter of The Rainbow, Asako meets a man named Ohtani. In the second, she meets her father, who turns out to be surnamed Mizuhara. I’m almost sad that Vintage didn’t try the world’s weirdest “brand synergy” marketing campaign, although of course from the vantage point of 2025, they’re surely glad they didn’t. In any case, maybe you’ll be pleased to find out that, in the novel as in real life (so far), Mr. Ohtani turns out to be the golden boy, an unusually driven moral exemplar who partially takes care of some of the messes left by Mr. Mizuhara. I guess waiting until 2023 gave The Rainbow more additional resonances than anybody could have bargained for.

A few others:

Asterisk – The Origin of the Research University

New York Times – Why Does Every Commercial for A.I. Think You’re a Moron?

Shan Rauf – How to Think About Time in Programming

Kieran Healy – American

Ironic Sans – It’s True: The JAWS Shark is Public Domain

Chemistry World – The young female astronomer who worked out what the sun is made of

Thanks for reading, and see you again soon!

He has a new album that I haven’t gotten to yet; maybe that’s for next month.

Answer: just one pair, and in the very last prelude to boot.