BWV 964 – Sonata in D minor (after Violin Sonata No.2 in A minor, BWV 1003)

Plus: Christian Gerhaher and Fischer-Dieskau, K-pop's sk8er bois, a new model for writing history, and more!

Allow me to break a bit from my usual format. I normally use this space to promote cool and interesting Native music that I’ve found. I guess what follows will do that too, but only incidentally.

Imagine looking for Native music and finding this Spotify playlist, with hundreds of thousands of listeners:

There’s real stuff on this playlist, including music by Joseph Fire Crow, Carlos Nakai, and Mary Youngblood. I quite like the Kevin Locke tracks on it, and Hovia Edwards’s playing (didn’t know her!) is very pretty indeed. Remarkably, somebody at Spotify seems to have actually gone through a tiny bit of effort to find major Native American flute players to put on this playlist—or at least to scroll down on the Wikipedia page and plug some names into the search bar.

I express surprise because these real performers come drowning in a river of pseudo-New Age garbage. In case you thought New Age music was already plenty “pseudo,” you should look into the framing songs of this playlist, from legendary artist, um, “Music Body and Spirit”:

Gloriously, none of these songs actually feature the pitch 963 Hz, which is probably a good thing considering how annoyingly high-pitched that note is.1

I would chalk all this up to AI slop, and indeed I think some significant amount of this anonymous junk was produced using machine learning. But most of it’s from before consumer-grade LLMs became available, especially for music. Somebody actually made, or at least procedurally generated by hand, this crap.

It’s hard to say if the same is true for Spotify’s playlist, even if they insist that such “curated” offerings are hand-picked. I’m not really sure what’s a worse scenario: a human deciding that the audience for this playlist doesn’t know or care about the difference, or an algorithm being unable to tell what’s Bill Miller and what’s anonymously produced “Native American Flute: Sleep Music.”

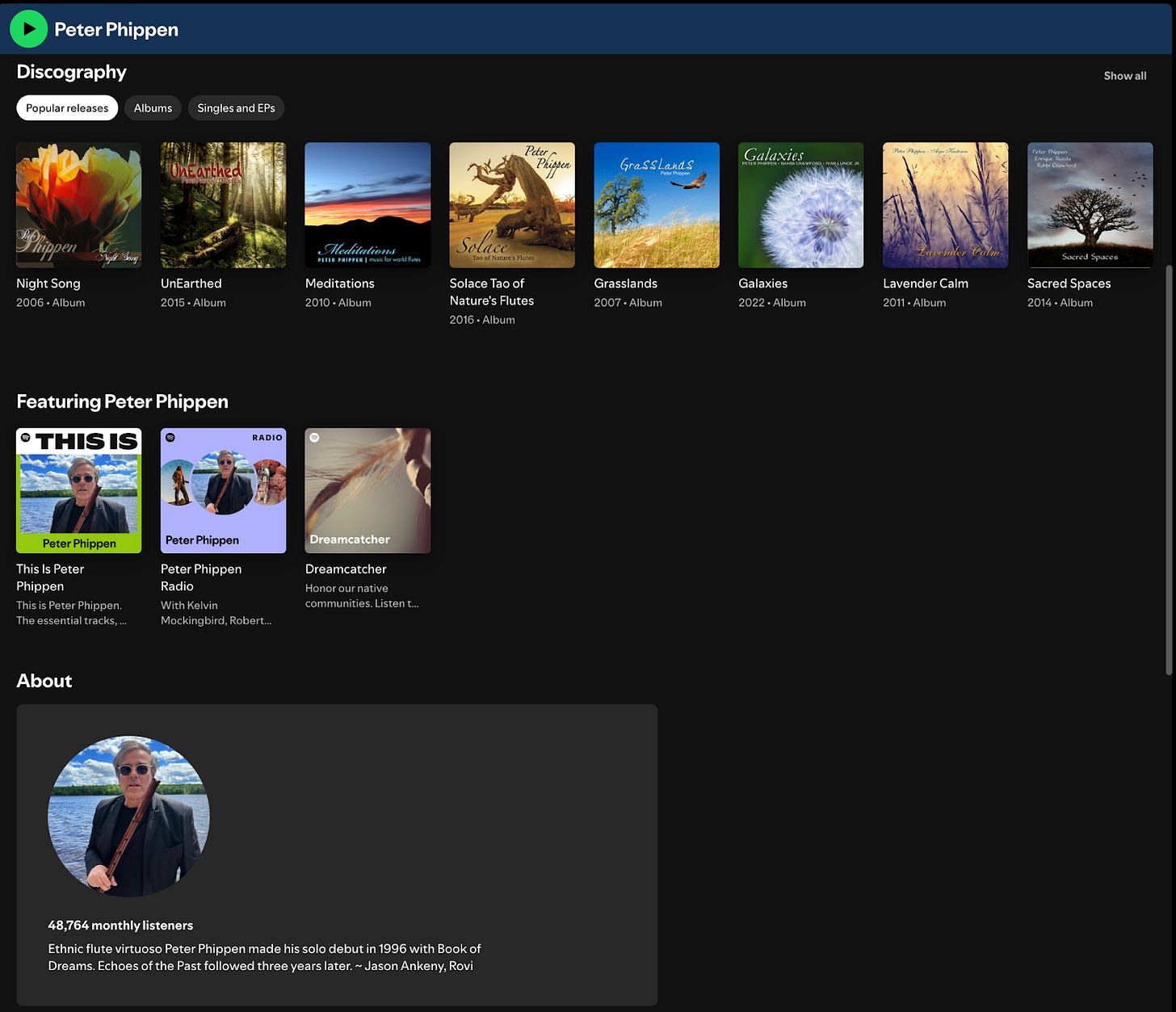

I know that finding algorithmic Spotify sins, even darkly funny ones like multimillion-play “963 Hz” songs without 963 Hz, makes shooting fish in a barrel look like something only Kim Yeji could do by comparison. What interests me more about this “Dreamcatcher” disaster is how easily “Music Body and Spirit” fits into the existing New Age junk that otherwise populates the playlist:

You get the idea.

I bet that a lot of these New Age types would probably be happy if you told them that their noodling was driven by a “divine spirit” or some such moving through them. It may not be “artificial,” but I would submit that this attitude makes New Age music the original slop produced by a foreign intelligence. In any case, the old-school and new-school versions are basically indistinguishable.

It’s more than a little sad to see Youngblood and Locke and Nakai thrown in with this stuff. But then again, it’s always been that way. If you read Craig Harris’s Heartbeat, Warble, and the Electric Powwow, you’ll see Nakai assert that “my music has nothing to do with New Age,” followed immediately by Nakai topping the New Age charts and winning a New Age Grammy. (Yes, there’s a Grammy for New Age. All four of Enya’s Grammys are in that category. Yes, Enya has four Grammys.)

All of that bums me out, but the very existence of New Age music kind of bums me out already. Don’t listen to “Dreamcatcher.” (Do listen to DREAMCATCHER.) But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t listen to a lot of the music on it. I can’t promise that it’ll retune your chakras or whatever, but there are other things you can get out of Kevin Locke. Spotify may not want you to know this, but they included real music on their playlist.

BWV 964 – Sonata in D minor (after Violin Sonata No.2 in A minor, BWV 1003)

i. Adagio

ii. Fuga. Allegro

iii. Andante

iv. Allegro

BWV 964 should be one of the crown jewels of the Bach keyboard repertoire. It’s a hefty piece of around 20 minutes, in just four substantial movements. It’s by far the best Bach sonata for solo keyboard, and everybody except Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle likes sonatas. (Although, be honest: did you know that Bach wrote solo keyboard sonatas?) And then there’s the fact that we already know and love this piece as one of the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin.

Actually, that’s surely part of the problem: chalk the piece’s relative obscurity up to anti-transcription bias. It’s particularly easy to get squeamish about playing a transcription when the original is this well-known. And I mean precisely this level of fame. Paradoxically, if a piece is any more famous, then musicians start to have less of a problem making their own virtuoso version of it. The Chaconne from the D-minor Partita gets tons of play from pianists and harpsichordists. But the A-minor Sonata doesn’t have nearly that level of listener recognition—while also being too famous to pass off as a “keyboard piece.”

It’s this awkward position that causes streaming services and websites like Presto Classical to insist on labelling Jean Rondeau’s recording of BWV 964 as “Sonata for Solo Violin No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003.” And they do so in spite of the actual track listing on the CD:

Characteristically, Rondeau’s branding is insufferable and his playing wonderful.

While you were distracted by Rondeau’s hair and the bizarre translation of “Meister Bach” (“French”) to “Herr Bach” (“English”),2 you may have missed that this CD also says “transcr. W F Bach.” That’s another reason people might not play BWV 964 all that often.

The thing is, there’s no good reason to think that Wilhelm Friedemann Bach has anything at all to do with this piece. Indeed, the only good reason that Neue Bach-Ausgabe editor-types have doubted that J.S. himself made the arrangement is that there’s no surviving autograph manuscript. And yet that’s not a particularly good reason at all, especially when the manuscript we do have is from two of Bach’s students, who put his name on the thing.

To be sure, they could just be attributing the original piece to Bach. But this piece simply doesn’t give any indication that a student or lesser composer did the arrangement. BWV 964 compares very favorably indeed with all the other doubtful Bach transcriptions that I’ve played. Bach at Bond listeners may remember the mild awkwardness and heavy simplifications of BWV 1039b and BWV 545b. Or indeed, you might know how “Bach” arranged a Sonatas and Partitas movement for organ in the “fiddle” fugue BWV 539/ii; again, the result is a bit clumsy and unidiomatic. BWV 964 is neither.

The greatest joy of an arrangement—aside from “hah, now I can play that too!”—is how it can shed light on the original piece. My first experience of this with the Sonatas and Partitas was in arranging the first movement of the G-minor sonata for organ to go with that “fiddle” fugue. My feelings about that piece are basically identical to what I think of the first movement of BWV 964:

I’m frankly confused by the “standard” interpretation of the Adagio that comes before this fugue in the original sonata. Basically every violinist, including the three [excellent Baroque musicians] above, plays that Adagio like it’s from a quiet middle movement of a funeral cantata. But, to my organist brain, the piece looks and sounds like nothing so much as the G-minor Fantasy BWV 542/i—just compare them visually, even:

versus

And no organist would play that piece with the thin, slightly washed-out sound that violinists like to adopt for the Adagio. The organ sound you would want is loud and in your face.

This is one of the ways in which I think that Henryk Szeryng, for all that he didn’t know about Bach, got this piece much more than many more recent and “informed” violinists. His white-hot (and indeed rather indiscriminately applied) intensity does a lot to bring out the drama of this Adagio.3

Another way to put the comparison would be to say—and this is an insight I owe to Brent Wissick—that these Adagios are Bach doing keyboard-style stylus phantasticus on the violin. What the arrangement helps to highlight is the extent to which the original piece is itself already adapting the music of another instrument. It already sounds like an arrangement.

Nobody needs the help to recognize that characteristic of Bach’s violin fugues. To me, these fugues resemble certain kinds of “foreignizing” poetry translations (or to complete the analogy, poems that are supposed to resemble translations) in which part of the appeal is that it’s so obvious that you aren’t reading the original, that you’re only catching a glimpse of what this art is truly like. I guess that sounds much more like a Romantic appreciation of these pieces than a Baroque one. Perhaps I do just have a Romantic ear for them, and maybe you do too.

In that case, you would expect to lose a lot when a violin fugue is relocated to its natural habitat on the keyboard. And indeed you do lose some of its charms. There’s no substitute for the glorious harshness of using triple and quadruple stops on every note to fill out a four-voice texture, nor for the odd yearning quality of passages where you have to infer or imagine missing voices. And if you don’t do much with the arrangement, there’s little to compensate for these losses. The “Fiddle” fugue, with its dull literalism, feels pretty thin as an organ fugue.

I doubt many people would say the same for the first Allegro of BWV 964. Whoever the transcriber is—and this is a drastic, surefooted, and otherwise thoroughly Bachian transformation—they really understood how to turn a violin fugue into one for keyboard. Consider how smoothly an imitative third voice is added to a two-voice episode (remember that the violin score is a fifth higher than the keyboard one; this is at 0:22 in the recording above):

Or how keyboard figuration is used to substitute for hacking away at the violin with triple stops (0:42; the first measure in the chunk of keyboard score below is m.32):

Indeed, throughout the fugue, the arrangement fills in gaps with streams of sixteenth notes (2:43; the keyboard chunk starts at m.125):

Note too how the arrangement constantly squeezes in little references to the fugue subject. Or listen to what happens to the ending—I’ll let you hear for yourself what the keyboard version is like (6:06):

All of this nervous filling up of space and creative keyboard-style rewriting is just incredibly Bach. It’s exactly what he did to Vivaldi. Why not his own pieces?

And I have to say that, despite my Romantic appreciation for the fragment-like quality of the violin fugues (or maybe we can hear them as picturesque ruins?), I much prefer this version. I like the fuller texture. I like how it sounds kind of like a hugely expanded version of the C-minor fugue from Well-Tempered Clavier Book I.4 I like that it has actual bass pitches. (The cello may be less agile and capable of complex counterpoint, but at least it sounds nicer as a solo instrument!) Bass, and the ability to spread out the violin’s cramped chords over several octaves, are also why I strongly prefer the BWV 964 version of the third movement as well. It just sounds right, like it was meant for keyboard.

You couldn’t really say the same for the last movement. There are solfeggietto-style pieces by Bach that look like this, with one line spread out between the two hands, but it’s still quite a shock to go from the richness of the previous movements to this:

It’s a very strange keyboard style, full of repetitions and echoes in addition to its distributed semi-counterpoint. The Allegro doesn’t quite sound like a miscast “violin piece” in this form, but it’s a far cry from Bach’s usual writing.

Except: this movement, with its single-line texture and incessant echoes, does bear quite a strong resemblance to another—very effective—Bach keyboard piece in D minor with doubtful authorship. Look familiar?5

If you don’t recognize that part, try:

Without wading back into the controversy over what the “original” form of Toccata and Fugue in D minor was, I’ll just say that this movement of BWV 964 is among the best pieces of supporting evidence for the hypothesis that BWV 565 was a violin piece originally.

And I think we can also draw a reverse conclusion. It may originally be a piece for solo violin, but BWV 964 is a fun, satisfying, and effective piece for keyboard. If the original hadn’t survived, perhaps it could have become the harpsichord’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor. It deserves that level of fame.

What I’m Listening To

Christian Gerhaher and Gerold Huber – Brahms: Lieder

Benjamin Appl and James Baillieu – For Dieter: Hommage à Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

It’s always tempting—and facile—to say “they don’t make them like this anymore.” It’s a surefire strategy for a critic trying simultaneously to show off their acumen and their ability to recognize rising talent. And it’s even better as a marketing strategy for classical record labels. Remember that? Wasn’t that great? Aren’t you sad you haven’t heard Schubert like that in a while? We’ve found just the thing for you.

When it comes to German art song, there’s little better nostalgia-bait than Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Fischer-Dieskau practically became synonymous with Lieder via his indefatigable production of box sets, his constant collaborations with leading pianists,6 and—let’s be fair—his exquisite care for each song that he recorded. You know how big he is because among “insiders” (I’m thinking of conversations with both singers and Lieder scholars), DFD is fairly uncool.7

So it makes sense for a musician like Benjamin Appl to hitch his wagon to the DFD star, especially when there’s a round number to celebrate. (Fischer-Dieskau was born in 1925.) And again let me not be unfair: Appl was Fischer-Dieskau’s final student, and genuinely seems to feel a strong connection with his teacher. He certainly is happy to talk about that connection, especially in a publication like New York Times or The Guardian.

As homages go, Appl’s album is pretty good. Like DFD himself, it finely balances obscure treasures (Fanny Hensel’s “Ach, die augen sind es wieder” is fabulous) with Schubert and Brahms chestnuts. There are pieces by Fischer-Dieskau’s father and brother. And there are traces of DFD’s style all over the recording: all that stretching and exaggeration of consonants, the little swells, the winking piano pullback from the end of phrases. I could be imagining it, but compared to his other recordings, Appl even sounds a bit like he’s putting on a mild DFD impression for this one. Cute!

Still, there’s something vaguely newfangled about Appl’s vocal production throughout the album; nobody would confuse him for Fischer-Dieskau or indeed any singer of that generation. Not that sounding “up to date” is necessarily a bad thing, but hearing the DFD mannerisms (“Rrrröslein, Rrrrrrrrrröslein, Rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrröslein rrrrrot”) on top of the mannerisms that seem to be current among Lieder singers—more extreme pianos and straight tone than any singer of DFD’s generation would ever use—is a slight worst-of-both-worlds situation. And of course the whole marketing apparatus is very foreign to the Fischer-Dieskau style. Not that DFD wasn’t a master marketer himself, but he existed in a very different media environment and targeted very different audiences.

Instead, a classic Fischer-Dieskau album would be called something like, well, Brahms: Lieder. And ironically I think that despite its lack of corresponding branding, Gerhaher’s album is a far better DFD tribute. Or at least it made me actually think “Wow, they don’t make them like this anymore.”

We’re not quite at the level of a critical shortage, but it’s increasingly rare to see this kind of “favorite [composer] Lieder” recital disc from a major singer. While I’m sure I’m forgetting something excellent, the most recent really great plain “Brahms: Lieder” recording I can think of is Bernarda Fink’s from 2007, and even for a composer like Schubert, I’ve been waiting since 2012 for a record to match Werner Güra’s extraordinary selection. To be clear, there’s still plenty of Lieder being recorded, and recorded very well indeed. But the dominant formats have shifted. While these “Wolf: Lieder”-type albums have receded, multi-composer recitals are still a staple, and so are recordings anchored by a major song cycle or set like Matthias Goerne’s 2016 Vier ernste Gesänge album (it’s revealing that the title isn’t just something like Brahms: Lieder). And singers like Goerne are still producing DFD-style traversals (complete or partial) of composers’ Lieder output.

Not that Gerhaher distances himself from these kinds of recordings either; he did recently finish a box set of the complete Schumann songs (a strong competitor for DFD’s traversal) and does his fair share of song cycle albums. The album under discussion even centers on Brahms’s complete Op.32, followed by the “Regenlieder” mini-cycle from Op.59. But otherwise, it’s a lovely tour through the hits—they’re mostly here, from “Wie bist du, meine Königin” to “Von ewiger Liebe” to “Die Mainacht”—and Gerhaher’s personal favorites. At any rate, the selection feels like a throwback to me.

As does Gerhaher’s singing. Indeed, it’s quite common (or even rote) to compare Gerhaher’s voice to Fischer-Dieskau’s, poetically precise German light baritones that they both are. Upon DFD’s death, there were a fair number of critics anointing Gerhaher as Fischer-Dieskau’s successor. And certainly Gerhaher learned a lot from DFD, as he’s happy to talk about in interviews if not in NYT op-eds.

That said, for me the nostalgic shock of Gerhaher’s singing comes not so much from its debts to Fischer-Dieskau as from its frequent resemblance to Peter Schreier. Sure, one’s a tenor and the other’s a baritone, but Gerhaher is one of the exceedingly few singers active today who frequently calls on the tightly-wound, slightly nasal, “chamber” sound that Schreier (and many other older Lieder singers) made his bones on. He never attempts to make his diction or sound particularly naturalistic: you’re never in any doubt that you’re listening to a Lieder singer.

And I think that’s all just wonderful. Appl’s DFD homage is nice, and certainly a worthwhile listen, but Gerhaher’s Brahms is a real treasure, both on its own and as a representative of a vanishing breed. Since he’s not willing to go to The Guardian to advertise it as such, let me simply say: if you’re nostalgic for Lieder’s “good old days,” then Gerhaher’s album is what you want.

billy woods – GOLLIWOG

An awful lot has been written about this album already, and I wasn’t entirely sure what I could really add. GOLLIWOG also doesn’t exactly lack for exposure, having gotten “Album of the Week”-type nods from a bunch of outlets and a feature in the New York Times. You should trust what Tom Breihan writes about an album like this much more than what I have to say.

Still, I feel compelled to say something, since this is easily the best album of any kind that I’ve heard this year, and indeed maybe my favorite hip-hop album since…DAMN.? Maybe even before? It’s been at least a decade. Also, check out the viewcounts on that music video (31k views, 21k subscribers, 3.4k likes at time of writing) or even the Spotify plays (157k for that song). billy woods may be a critic’s darling but he could still use a bit of a boost finding listeners.

I have to be careful writing about music like this because I’m about as close to the target audience as it gets. Like Earl Sweatshirt (a canny interview pick for that NYT piece above), woods is the son of professors and literati. So you get interviews like this:

A. Westerns definitely figured into this in the sense of Blood Meridian.

Q. Do you want to tell the people what the title “Zulu Tolstoy” is about?

A. Well yeah, it’s a Saul Bellow quote. He said, “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus?” He caught a lot of flack for that, but basically I guess he was trying to say something about cultural relativism and Western civilization, things that I find both interesting and amusing. Again, my mother is an English literature professor. I grew up with Shakespeare, the canon. My mother lives by that shit, but at the same time my mother is not in any way thinking that other societies are lesser than… you know, it’s a very European thing to be like, “Hey, we do this, so who do you have that does this?” or to view art as if there’s the only way it can work.

Unsurprisingly, woods’ lyrical references are like catnip to someone PhD student-types. The opening track of GOLLIWOG starts out talking about Cecil Rhodes and ends with nods to Audre Lorde and Deng Xiaoping. “Maquiladoras” includes an entire verse summarizing Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks. “Corinthians” is framed by passages from Lu Xun’s “Diary of a Madman,” spoken in Chinese and English at the same time.8 “Golgotha” includes long passages in Georgian; “Waterproof Mascara” ends in Japanese. There’s Dostoyevsky on “Make No Mistake” and The Tempest on “Pitchforks and Halos.” And there’s even a nice swipe at Tom Thibodeau on “STAR87,” although I guess there’s no longer any need to worry about how many minutes he plays Mikal Bridges.

Then there’s the fact that the music itself—the beats—is also aimed squarely at older overeducated types. Just like Christian Gerhaher (now there’s a comparison you won’t find anywhere else!), woods’ musical style is a serious throwback. His genre has been called “horrorcore” for its dark cinematic imagination, downcast tone, and bleak subject matter. (“BLACK XMAS” is a storytelling and lyrical masterpiece—with no references to postcolonial theory or classic literature—but also a pretty brutal set of lyrics.) And that’s all true, but it doesn’t get at the fact that these songs bear little resemblance to horrorcore exemplars Eminem and (sigh) Insane Clown Posse. For that matter, they barely resemble anything in the current vocabulary of hip-hop either.

To me, what much of GOLLIWOG really sounds like (in terms of beats and production, not rapping) is the Wu-Tang Clan. Now, that’s vacuously true in the sense that every hip-hop producer since 1992 has been touched by RZA’s influence; and it would be have been an obvious and unhelpful thing to say for a lot of rappers in the ‘90s and ‘00s, given how many direct imitators he had. But this grainy analogue sound is now quite rare (even as artists like Doechii have revived a lot of aspects of ‘90s hip-hop production). And the specific musical sources that woods’ many producers draw on just sound incredibly 36 Chambers. Want washed out dissonant jazz piano loops? Check out “Cold Sweat” and “BLK XMAS” and “Born Alone” and “Lead Paint Test” and you get the idea. And of course the liberal use of audio from old movies is very Liquid Swords.

Equally old-fashioned is how woods’ and the guest artists’ verses sits within the production. There aren’t any skits on this album (basically nobody outside of BTS does skits anymore), but there is a related tendency to give the rapping room to breathe, to let the samples (and the movie scenes, and Lu Xun) take over. The rap verses on GOLLIWOG are often a relatively low proportion of a given track’s runtime. It’s a startling contrast to the prevailing format of recent overstuffed streambait albums. I love it. They don’t make them like this anymore.

Duan Yaocai 段躍才 – Fu’s Mother Died 傅羅伯尋母

I’m quite late to this recording (released at the end of 2021), but I’m still willing to plug it here since it only got any kind of broader exposure this past month. (Hat-tip, as always, to World Music Central.) Unlike Benjamin Appl or billy woods, Duan Yaocai is not getting glossy NYT coverage. And he was a really fabulous musician who deserves to be heard more widely. (Duan passed in 2023.)

The album’s framing is a bit strange. Pan Records owner Bernard Kleikamp, who made the recordings (from 1995 to 2016) seems insistent on the idea that Baizu dabenqu is a kind of sister form to the blues.

Dabenqu also goes with a certain style of singing, phrasing and song presentation, almost similar to blues. Duan Yaocai who sings about pains and sorrows of the Bai in the regional dabenqu repertoire, accompanying himself on the dabenqu instrument sanxian, is definitely a blues singer in his own respect, a dabenqu blues singer.

Thus the invocation of blues (in blue text) on the album’s cover art.

I have to admit that I don’t really hear it. It doesn’t help that there’s relatively little actual dabenqu singing on the album (“Wenshen diao” and “Qing Chang”), and what there is sounds very little like the blues, both sonically and structurally. (The format of dabenqu is lines of 7, 7, 7, and 5 syllables, as opposed to the blues’s AAB stanzas.) Instead, the album is dominated by Duan’s skillful performance on a whole host of traditional instruments across families: virtuosic plucking on the sanxian; piercing yet fluid blowing on the suona (a rare suona recording that doesn’t make you want to cover your ears and run); full-breathed and agile dizi trills; and marvellously suave bow control and glissandi on the erhu.

I wish I could dive more into what’s specifically Baizu about these performances. Then again, that may not be the most useful lens through which to view them. As Susan McCarthy has pointed out, a large portion of what’s marketed as “Baizu culture,” including (or especially) dabenqu, has been drastically reshaped in the postwar effort to consolidate, characterize, and pigeonhole each official minority of China. Baizu music has in the process come to represent an antique survival, a relic of Tang-dynasty performance (perhaps relating daqu 大曲 and dabenqu 大本曲?). Even as this music grows ever more hybrid and modernized, it becomes essentialized as an authentic and traditional expression of an ancient culture.

So don’t feel too bad if you’re worried about lacking sufficient cultural context for Duan Yaocai’s performances. At the end of the day, he was just another working artist trying to make the best and most appropriate music he could. Or rather, he was a lot better than that. Performers this good are rare; listen to the album. I’m only sorry I couldn’t get to it while Duan was still with us.

KickFlip – Kick Out, Flip Now!

They very much do make them like this anymore. JYP’s new boygroup KickFlip sits at the intersection of a number of recent K-pop trends. But that’s not a knock on them. Indeed, with this album, KickFlip have woven these threads into probably my favorite K-pop release of the year so far. (If that doesn’t sound very impressive, you might need to be reminded that IU has a new album.)

The most obvious trend is in the name. As their invocations of skateboard culture (“Let’s go, to the half-pipe we built ourselves”) would imply, KickFlip’s concept is probably K-pop’s most overt and full-throttle attempt to jump on the “Y2K revival” trend. But unlike how NewJeans and their ilk have imitated PinkPantheress by evoking Drum ‘n’ Bass, KickFlip have instead followed in the footsteps of K-pop acts like Choi Yena: their version of “Y2K” is pop-punk, and their model is Olivia Rodrigo. (Yena flew a little too close to the sun invoking this model, which is a shame given that “Hate Rodrigo” is a fabulous song.)

The pop-punk influence is not subtle. “FREEZE,” even more than Yena’s and other K-pop versions of this trend, actually goes for vaguely pop-punk boilerplate in the lyrics (somehow credited to a dozen different writers). It is really funny to hear an idol group presumably composed of high school dropouts sing literally “We don’t need no education!” (although “why don’t you leave me alone” seems like an entirely appropriate warning to fans). It’s even funnier to hear KickFlip almost completely steal the tune of their pre-chorus (“Oneul, haru…”) from Blink-182’s “All the Small Things” (a song and band that I’m told had very little if any presence in Korea). It’s certainly not the most egregious “K-pop copycat” of all time, but like so many of those rewrites, it’s an attempt to evoke not just a tune or a beat, but an entire cultural formation surrounding a genre. (“Complicated!!” is also a very straightforward pop-punk song, but it doesn’t steal anything beyond its title from Avril Lavigne.)

More generally, pop-rock’s fortunes have been on the rise in Korea for a couple years now. WOODZ’s popularity has exploded even as he completes his military service. DAY6, 10 years into their career, have never been so popular. JYP has long been interested in “idol band”-type branding, and the time has never been better to go back to that sound.

KickFlip are also jumping on a recent turn in K-pop boy group music toward high-energy, major-key, and generally upbeat vibes. I associate this trend especially with TWS (themselves evoking the “freshteen” era of labelmates SEVENTEEN), but you can also hear it in RIIZE and NCT Wish. After a few years of boy-group music being dominated by edgy, downtempo, and noisy offerings from Stray Kids, ATEEZ, and NCT 127, the pendulum was probably bound to swing back. Even KickFlip’s offstage (variety) branding seems calculated to evoke happy teenagers instead of moody ones. (Yes, Donghwa really does introduce his position in the group as “The weird one.” Gotta love boy group marketing.)

That said, KickFlip do also embrace elements of the darker “noise music” sound. Some of the album tracks (especially “Electricity”) have a very strong Stray Kids vibe indeed, Phrygian riffs and all. There are even moments in “FREEZE” itself—the first chunk of the chorus, when the title word comes in—which remind me of something between the choruses of NCT U’s “Baggy Jeans” and Stray Kids’ criminally underrated “Side Effects.” Stray Kids, of course, are KickFlip’s labelmates.

KickFlip also follow on from TWS in their embrace of sounds from J-pop. Indeed, unlike TWS, they actually have two Japanese members, and both Amaru and Keiju are involved in songwriting and production for the group. And, just as with their “Y2K” concept, KickFlip’s J-poppy sounds are quite overt, much more so than TWS’s. “Before the Sun Explodes” uses a chiptune version of exactly the kind of high-speed, meandering, all-over synth/keyboard line that dominates the music of YOASOBI and much other anime-style J-pop. (Contrast these synths with the organized and tuneful—very K-pop—use of chiptune sounds in Red Velvet’s “Power Up.”) The chaotic swirl of songs like “Skip It!” and “Code Red” evokes the world of Japanese hyperpop. And I swear the opening of “FREEZE” is designed to sound like “Bling-Bang-Bang-Born.”

I don’t think it’s entirely a coincidence that these trends all go together. Power pop, pop-punk, and other forms of pop-rock have remained commercially viable in Japan for far longer than in other countries. The Y2K era was the most recent golden age for this kind of music in the West. And Japanese musical styles have never been so palatable in Korea. KickFlip may be mashing together a lot of different influences, but there’s a deep logic to their choices. For all this music’s cheesiness (“How We KickFlip,” good grief), it’s smartly thought-out, propulsively fun, and damn catchy. If “FREEZE” sparks its own wave of imitators, that’ll be a pretty good outcome.

Also liked…

Carin van Heerden and L’Orfeo Barockorchester – Telemann: VI Overtures à 4 ou 6 (1736)

Moontype – I Let the Wind Push Down On Me

Marshall Allen’s Ghost Horizons – Live in Philadelphia

Zoé Basha – Gamble

Carolyn Wonderland – Truth is

Ammar 808 – Club Tounsi

What I’m Reading

It’s always dangerous to try to say anything about a book when you encountered it via a substantial review. Doubly so for an academic book, and triply so when it’s not in your field. I’m going to try it anyway: Peter Thonemann’s rave in the TLS convinced me to read John Ma’s Polis: A New History of the Ancient Greek City-State from the Early Iron Age to the End of Antiquity, and I really want to talk about it.

I’m obviously neither a classicist nor a historian, so if you want an evaluation from somebody who knows the relevant literature, read Thonemann’s review. For that matter, Thonemann gives a fabulous summary of the main part of the book and its interventions in historical debates, so I’ll just give a thumbnail sketch here. Polis is a history of local political formations in Greece up to around the fourth century C.E., and makes a strong argument for deep continuities along that whole timespan. Ma begins right at the beginning, covering how poleis originated from “clustervilles,” how metropolitan-countryside relationships developed, the origins and functions of Greek legal institutions, and the consolidation of poleis into “closed” and “open” societies (crudely: Sparta vs. Athens). Throughout, he focuses on how elites and commoners negotiate sharing power, goods, and space with each other, how the public realm is constituted, and the proliferation of rough egalitarianism. After the spasms of the Peloponnesian and related Wars (a Greek “Hundred Years’ War”), Ma sees a “great convergence” toward the “open,” democratic model in the later fourth century BCE.

Probably the most fascinating part of Ma’s history—and the subject of his prior work—comes in the period after 350BCE, a time when many histories of “Ancient Greece” simply end. Despite the conquests of Alexander (“Alexandros III” in this book) and then the Romans, Ma makes a convincing argument that poleis had substantial autonomy to govern themselves and interact with each other, right up until democratic institutions faded away in the third century CE. Moreover, he makes a case for the Greek polis as Imperial Rome’s model for forming and reforming cities and other local jurisdictions, especially as it colonized West Asia.

It’s hard to make this history sound as exciting as it reads. I’m not typically one for political science or political history, but Ma’s analyses of poleis as evolving social formations are as compelling and lucid as they could be. There’s a palpable enthusiasm to his writing, especially when it comes to challenging or controversial ideas. And it’s reasonably accessible with a decent foundation in Greek history; the (newly-revised) Pomeroy et al. Brief History of Ancient Greece is more than enough background.

Thonemann’s review glosses over two of my favorite features of Polis. One is its wide range of source material. Ma seems genuinely excited to present as many obscure epigraphic sources as he can, loading the book with translations of fragmentary inscriptions from cities you’ve never heard of. (They’re inevitably well-chosen, even if he at one point dryly admits to having a certain predilection for case-studies.) He loves discussing sources and objects that only survive via obscure German or French journal articles. And on the other hand, he also makes extraordinary hay of the very best-known literary remains of Ancient Greece. Thonemann may complain that the Homer chapter is too short—and maybe it is—but I found Ma’s drive-by readings of classic literature (Hesiod, Herodotus, Aristophanes, Aristotle, and the Second Sophistic all get the same treatment) to be highlights of the book. He keeps it brief each time, but always makes an incredibly sharp intervention: the pages on Thucidydes mainly demonstrate that anybody talking about a “Thucidydes trap” has completely misunderstood the text.

Then there’s the final section of the book, which I honestly think Thonemann simply mischaracterizes. Rather than constituting a series of “synthetic essays,” Part VI is, as Ma describes it, a set of “rolling conclusions,” which is to say that he writes no fewer than six different conclusions to the same history. Far from being self-indulgent, this is easily the best part of the book, and a strategy that I now wish every historian everywhere would adopt for major texts. Each of these conclusions is also something of a counterargument: Ma takes the opportunity to address each of his book’s blind spots in turn, and rather than refuting possible objections, he simply considers what it would be like to reframe his history in those terms. What if we looked at poleis as societies (emphasizing ritual, gender, and social interaction) and not clusters of institutions? What if we viewed them as artifacts of discourse and ideology? Why doesn’t Ma emphasize class struggle more? What if poleis turned out to be awful in practice? What if they were always awful, even in theory? Not that Ma doesn’t defend his choices from among all these alternatives, but he does so in an extraordinarily even-handed fashion, letting each of these competing histories emerge as a real possibility in its own right. Since Ma gives a pretty detailed summary of the preceding chapters at the beginning of Part VI, you could even read this section by itself.

One final thing. It’s now deeply unfashionable to include remarks like this in any kind of review, but I wouldn’t call what I’m writing here a review, so here goes: Polis is a beautifully produced book. I subjected this book to a huge amount of abuse over the months it took me to get through it. It was dropped, flattened, forgotten in backpacks, spilled on, pried open, and otherwise maltreated. It still looks and feels great. The typography and page layout, the actual paper, and the binding are all excellent. Academic presses (especially Oxford, Cambridge, and Springer) have really been cheaping out in recent years, and Princeton has resorted to print-on-demand for their back-catalogue, but they apparently still know how to put out a real book. It probably shouldn’t go on a coffee table, but Polis is an object (as well as a text) to cherish.

A few others:

Planetizen – Rethinking Redlining

Harper’s Bazaar – Erica Kennedy’s Hip-Hop Satire Predicted the Future

Hyperallergic – Manufacturing “Black Fatigue” in the Art World

Financial Times – Taiwan’s double, double toil and trouble

Science – A vector calculus for neural computation in the cerebellum

Kitten – College English majors can’t read (followup)

Thanks for reading, and see you again soon!

They are in the right key (wrong octave throughout), and that seems to be a pattern for the higher-pitched members of the “7 Chakras Solfeggio Frequencies.” Meanwhile, the 417 Hz album actually does use its namesake pitch throughout.

Don’t even get me started on the punctuation.

Similarly, Pablo Casals’s clenched-jaw approach to Bach makes a lot more sense out of the Prelude to the fifth Cello Suite than most current players do.

Coming to a Left on Reed near you soon.

Incidentally, the last movement of BWV 964, and its relationship to the forte-piano echoes in the BWV 1003 version, is one of the better reasons to play these parts of the D-minor fugue on alternating manuals.

In addition to the Gerald Moore recordings you may be thinking of, DFD also recorded Winterreise with Daniel Barenboim, Alfred Brendel, Jörg Demus, Murray Perahia, Maurizio Pollini, and probably some other famous character I’ve forgotten about. (Demus, of course, wins.) Then there are the Brahms, Schubert, and Wolf recordings with Sviatoslav Richter.

Elly Ameling is still cool, as far as I can tell.

Thus literalizing the meme I’ve been sent more times than I can count:

yes. You had me at Bach Solo Keyboard Sonata.

There was a time when Brahms Op 32 was in the woodshed...now it has a place by the fire. Not sure what happened or why.

Spare a thought for the elderly who grew up on Szeryng.