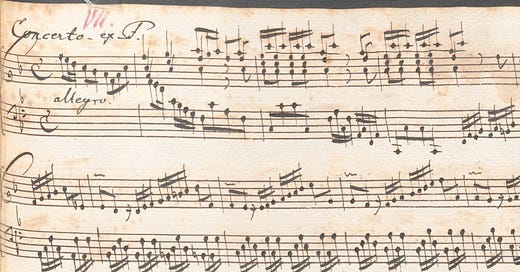

BWV 978 – Concerto in F Major (after Vivaldi, Op.3 No.3, RV 310)

Plus: Adèle Hugo rediscovered, Taeyeon's Letter to Herself, Ancient Africa in global history, and more!

What’s in a name? Quite a lot if you’re Donnie Edenshaw. With this name, Edenshaw (Gaju Xial) inherits the legacy of Charles Edenshaw (Da•axiigang), one of the relatively few true “brand names” among First Nations artists.1 I know Charles Edenshaw best for his magnificent work in argillite—simultaneously boldly etched and subtly graded—but he also worked in wood and metal, in addition to painting on a variety of surfaces. Donnie Edenshaw seems to bring that multimedial versatility to his own artistic practice as well.2

Which brings us to music. Edenshaw, according to the biography linked above, was active as a singer and a dancer before embarking on his carving apprenticeship. And this year he’s brought his years of musicmaking to bear on a record, a self-released album of Haida Village Songs. The arrangements are very simple: just Edenshaw himself singing and drumming.3 After all, the point wasn’t to produce anything fancy. Rather, he says,

I pretty much just wanted to do this for the younger generation and people who are further away from us to keep them in touch with our culture and for others to hear our songs. An[o]ther Avenue besides facebook live.

If that’s his point of comparison, I want to know what kind of Facebook Lives Edenshaw has in mind. Both the audio quality and level of musical ambition are much higher than these comments would imply: these are great, thoughtful, moving renditions of these songs. I love his voice and his drumming sound. Beyond basic comments like that, I don’t think I have the cultural competency to properly evaluate (or even really describe) his performances, but at least for me it’s a satisfying and stirring gift of music. Listen to it—and consider looking into his art while you’re at it.

BWV 978 – Concerto in F Major (after Vivaldi, Op.3 No.3, RV 310)

i. Allegro

ii. Largo

iii. Allegro

I may have whined a little bit last month about pianists not playing the Bach Toccatas, but when it comes to his concerto transcriptions I truly have no idea what’s going on. I don’t know why these pieces aren’t recital warhorses for every kind of keyboard player (including organists).4 Everybody loves Vivaldi, Bach had great taste when it came to picking pieces to arrange, and these pieces fill a big gap in the keyboard repertoire. (Remember that there are no keyboard concertos by any composer before Bach.) Why aren’t we more jealous of the violinists, cellists, and even mandolin and bassoon players who have oodles of Vivaldi to play? Do we just hate fun?

Maybe it’s a lingering bias against transcriptions, even if this kind of music has pretty much always been the bedrock of the keyboard repertoire.5 One would think that the transcriber being literally J.S. Bach would help matters, but here we are.

So maybe it’s Italy instead. There’s almost no Italian music that pianists or organists are enthusiastic to play; even Scarlatti is a bit of a hard sell for pianists nowadays, and there aren’t too many organists who love playing Frescobaldi. (Harpsichordists, to their credit, don’t have qualms about either. But I don’t really see them lining up to play Bach/Vivaldi either.)

If you had to boil the Germanic musical prejudice against Italy—and Vivaldi in particular—down to one element, it would surely be “simple repetition.” It’s the canonical contrast between Beethoven and Rossini: one develops his themes, while the other just repeats things until he gets the effect he wants. The same critique tends to be leveled at Russian composers too. If Tchaikovsky likes a tune, he’ll just repeat it, even in the context of a symphony. And Theodor Adorno pretty much replicated the Beethoven/Rossini dichotomy for Schoenberg and Stravinsky.

But it always seemed a little ridiculous to me to complain about Stravinsky’s exercises in musical copy-paste.6 Sure, the “Danse Sacrale” from the Rite of Spring is basically a long series of cut-and-pasted snippets, permutations of the same four or five elements. But they’re always perturbed slightly, made just different enough to through you off your equilibrium. You can know a piece like Rite or the Three Pieces for String Quartet really well, and still be utterly unable to correctly time the placement of the accents, the moment when the next snippet comes back in. It’s very repetitive music that’s anything but predictable.

I would submit that Vivaldi, an infamously repetitious composer, is doing a subtle version of the same thing. Yes, subtle; it’s not exactly Vivaldi’s reputation (and sure as hell isn’t Stravinsky’s), but in his best pieces, it’s little differences between statements of the musical material that make the piece tick.7

Take the first theme, a typically Vivaldian exercise in making plain F major (scale, chord, arpeggio, key) keep your attention for two straight measures:8

As usual, Vivaldi takes this theme for a spin through a bunch of different keys (I, V, iii), and its recurrences help set landmarks in the flow of the music. Those key changes by themselves create some amount of variety, but just as important are some of the changes he makes to the theme along the way. So when the music is in A minor, the main theme can be used to end a phrase instead of beginning one (1:17):

It can be played in quick succession without its continuation (1:44):

Or its continuation can be developed into its own thing (0:40):

The effect is never as disorienting as Stravinsky’s rhythmic dislocations are, but it’s these differences that keep the music going, that allow for the combination of predictability with mild surprise that makes Vivaldi so fun.

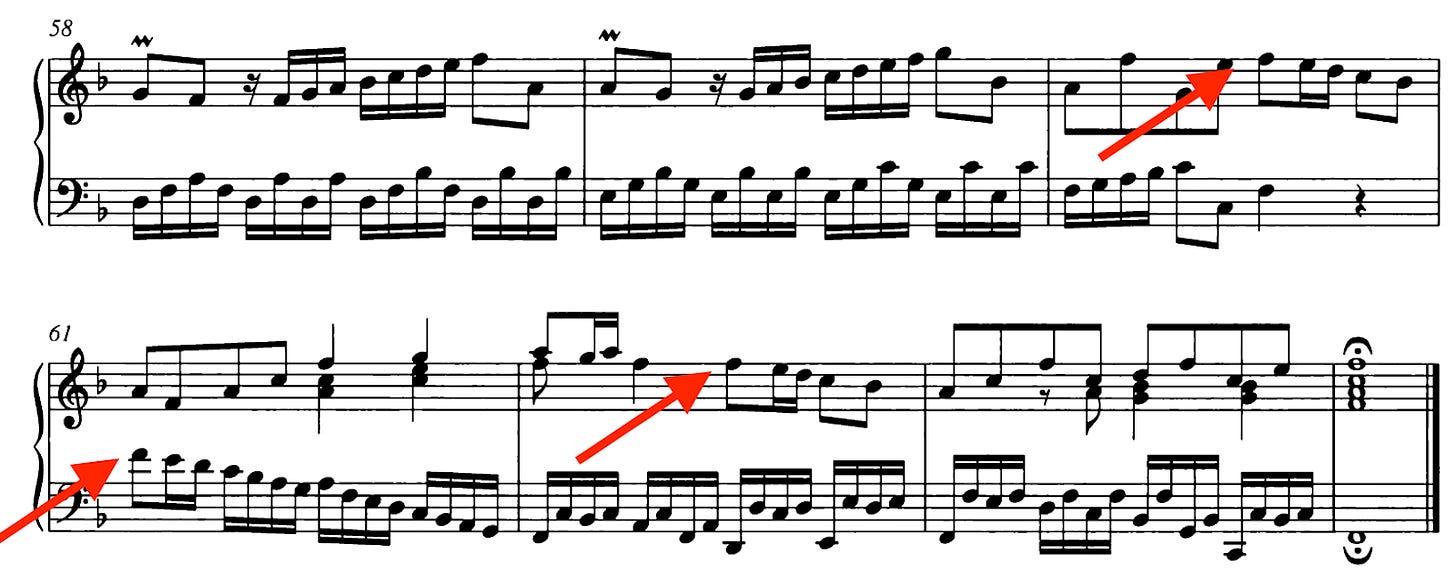

Bach learned a lot from Vivaldi, but subtlety was not part of it. (If you want a recording of the Vivaldi in order to make the comparison, I like this one.) Where Vivaldi keeps things simple to maximize contrasts, Bach almost always has to add something, to fill up space and time. Above, I gave the main theme the way Vivaldi wrote it, but here’s what Bach gives us:

If you can do a nice little imitation in the bass, then why not? And this extra copy of the theme does in fact give Bach the opportunity to add a few subtleties of his own. Here’s the ending of the movement (2:15):

If you compare the two examples above, you may notice that the bass comes in a half-bar earlier the second time. That matches a nice little motor-revving thump in Vivaldi’s bassline. But there’s no match for the busy left-hand figuration that Bach adds. (Or the new harmonization of the final three measures.) An exciting ending, enabled in huge part by the game of “copy-paste with a difference.”

Something similar happens in the third movement. (The second movement is very pretty and I have nothing to say about it.) Even more than in the first movement, Bach is here trying to fill every nook and cranny of the music with running sixteenth notes. Here’s Vivaldi (0:35):9

And here’s Bach:

Just to hammer the point home, here’s Vivaldi again (0:58, not that you’d be able to tell):

And Bach’s “version”:

Good grief. Sure, repeated notes aren’t super nice to play on the harpsichord, but this is basically a different piece. And the effect is completely different: Vivaldi has a cuckoo-like soloist ping out over spare chords, while Bach gives absolutely no distinction between foreground and background. And you can almost feel the energy of “recomposing” spill over into the passage that follows (1:10):

That spurt of thirty-second notes? Bach. The added third voice? Bach. That crazy awkward left-hand passage in m.82, which seems for all the world like it should be a product of overliteral transcription?10 Nope, it’s all Bach.

So this concerto is by no means a simple transcription, and there’s actually quite a bit of Bach in it. BWV 978 retains much of its Vivaldian charm—especially in its simple, clear-cut, rhythmically vigorous themes—but in many places that Italian sunshine is obscured by clouds of German ink. Bach can’t stop himself from making the piece conform to his preferences. So tell your pianist friends: this music is “Bach after all,” which means it’s “safe” for them to play. Who knows—if they play it, they might even learn to like Italy along the way.

What I’m Listening To

Kendrick Lamar – GNX

Thank goodness I don’t write proper reviews here, or feel the need to “cover everything.” I’m glad to have been spared from coming up with anything at all to say about Ariana Grande or Taylor Swift’s albums last year (both fine), the continued implosion of Katy Perry’s career, or the endless string of perfectly good but unexciting recordings of standard symphonic repertoire that major orchestras continue to churn out. And most of all, I’m glad that I didn’t feel the need to say anything about this year’s most important musical event, the whole Drake–Kendrick thing. I have nothing to add to the consensus: Drake got completely flattened, and the feud brought out the absolute best from both sides.

Now, it’s not like there’s any less commentary on GNX. How could there be? A surprise drop from maybe the most critically-acclaimed living musician deserves attention, and you can read plenty about this album elsewhere. (As usual, I really like Israel Daramola’s commentary.) But this time I feel like the congealing consensus is missing something.

The general throughline you’ll find in reviews is that this is Kendrick’s victory lap, a joyful collection of radio-friendly hits (pop-whisperer producer Jack Antonoff is credited all over, and seems to be working to counter his own reputation). The album must be designed to capitalize on the “Not Like Us” moment. It’s also, most people seem to agree, really good.

That’s surely all true. GNX is infinitely more welcoming than 2022’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. “tv off” has to be heard as “Not Like Us” part 2. And, yeah, the beats hit hard and there is some really great rapping. The dialogue on “reincarnated”?

Tell me every deed that you done and what you do it for

I kept one hundred institutions paid

Okay, tell me more

I put one hundred hoods on one stage

Okay, tell me more

I’m tryna push peace in L.A.

But you love war.

Wow.

Still, to me the most interesting thing about this album isn’t its place in Kendrick’s career or this year’s feud, but rather what it says about the hip-hop landscape today. Specifically, I’m fascinated by GNX’s massive shift toward including Latine artists. The sound of mariachi singer Deyra Barrera frames the album, kicking off the opening, closing, and central tracks. Her story has been talked about a reasonable amount. But there are also features from Lefty Gunplay and Peysoh.

To be fair, when I first heard the name “Peysoh,” I thought this album was even more in bed with Latin music than it already is. (Also: “Wow, Peso Pluma is a way better rapper that I would have expected!”) But even without the narcocorrido star, it’s a pretty remarkable gesture for Kendrick to give such pride of place to Spanish-language lyrics and Latine artists.

The inclusion of Latin music was probably intended to make GNX represent L.A. as fully as possible. (If you’re not sure why that’s relevant, start with the song literally called “dodger blue.”) Maybe that’s all it was intended to do; well, beyond also giving a platform to some cool artists that Kendrick had discovered. I could be overthinking it.

But these tracks—and this album as a whole—really do sound to me like another sign of American mainstream media’s double globalization. On the one hand, you have the widespread popularity of Marie Kondo and Squid Game, the new willingness of American audiences to get over the “one-inch tall barrier of subtitles.” On the other, you have American-made media itself going more and more global, including more and more foreign sounds and ideas.

Specifically, I can’t help but hear Kendrick’s mariachi intros in relation to Megan Thee Stallion’s recent work, her freewheeling integration of Japanese on tracks like “Otaku Hot Girl” and of course “Mamushi.” Megan and Kendrick have utterly different vibes, and Deyra Barrera is neither TWICE nor BTS’s RM (collaborators on the repackage album she dropped a month ago). I’m not sure either would be flattered by the comparison. Still, at least for me, GNX and MEGAN: ACT II seem to fit into the same broad trend.

It’ll be fascinating to see if the trend continues, to see where each of these artists go from here. Maybe there really is Peso (and not just Peysoh) in Kendrick’s future. Or it could be his turn to go K-pop. In which case—might I make a recommendation?

Jean-François Verdier and Orchestre Victor Hugo – Adèle Hugo: Mélodies sur des poèmes de Victor Hugo

Shows what I know. I was sure this album was a compilation of pieces “inspired by” Victor Hugo’s daughter, perhaps with even the weaker connection that the poems were written for or about her. There is no Grove or MGG entry on Adèle Hugo. If you search for her on IMSLP, you’ll find one piece dedicated to her. But here she is: nineteen pieces and about an hour’s worth of music to peruse. There are instrumental pieces and song cycles, miniatures and grander statements. Adèle Hugo, composer, has arrived.

In a month where a nice but rather slight newly discovered Chopin Waltz has gotten all the buzz, it’s a bit of a shame to see this much larger-scale and probably more interesting discovery come and go with a single review and basically no promotion from the label. (It’s never a good sign when a reasonably established outfit like Alpha releases an album and there’s not a single Youtube video to go with it.) Shame on them, and slightly flummoxing that conductor Jean-François Verdier and composer Richard Dubugnon haven’t done more to get the word out. (Or maybe they have, in which case shame on every outlet they contacted.)

It’s especially dismaying because Adèle Hugo is hardly an unknown figure. Yes, there’s her famous father—why wasn’t this album advertised as containing the “first musical Les Mis”?—but there’s also the heartbreaking story of her life. If François Truffaut has made a movie about you, surely the public unveiling of your music deserves a little attention.

I’m not going to turn around and say that these are “newly uncovered masterpieces.” The tragedy of Adèle’s story seems to include a complete lack of parental support; this is not the story of a Fanny Hensel or Lili Boulanger who was encouraged to really develop her musical talent. So, it would be basically impossible for Hugo’s music to have reached the heights of a Hensel or a Boulanger (a very, very high standard, to be fair). Instead, we have music that Ambroise Thomas seems to have liked, and which is indeed about as good as Ambroise Thomas. They’re nice tunes in the mold of Gounod’s songs, or even Berlioz at his less dramatic moments. But don’t let me sell Hugo short: the longer songs (including album-ender “Priez pour les morts”) can really be quite impressive. Hugo was obviously quite immersed in music, and on occasion some of the intensity of her personality shines through.

“Masterpieces” or not, I’m glad that Verdier and Dubugnon gave these pieces a chance (although did the songs really need these orchestrations?). Having a huge name like Sandrine Piau on board for a project like this ought to have been a huge boon for publicity; if it really turns out not to be, then at least we have her wonderful singing. The performances in general are absolutely polished and committed. (Frankly, I wish there were recordings this good for the music of composers like Hensel and Boulanger who didn’t need to be “rediscovered” from manuscripts. When is a singer of Piau’s caliber and notoriety going to take on Clairières dans le ciel?) This record should put Adèle Hugo on the map. I’ll look forward to reading her Grove and MGG articles soon.

Mayra Andrade – reEncanto

Mayra Andrade is new to me, and if you’re in the same boat I can say that this is a pretty great place to start. reEncanto, as Andrade’s first live album, also gets to function as something of a greatest hits, albeit in newly stripped-back arrangements. As you can see in the video, it’s just her and guitarist Djodje Almeida (Andrade does most of the percussion you hear). Almeida, as you’ll hear from spots like the outro to “Navega,” is a wickedly good guitarist; I hope to see more releases from him.

But it’s Andrade who really sells the record. They’re all her songs, and she really owns them, letting her singing range from husky and smoky to sardonic speech-singing, to outright wailing (but somehow controlled?), often in the same song: “Konsiénsia” is a real tour de force. Equally important for her vocals is Andrade’s lavish attention to the languages she sings in. “Odjus Fitchádu” sounds like a playground of Cape Verdean Creole that Andrade is giddily exploring. Some of the songs are genuine pop hits, or at least would be in a just world. Try not bopping along to “Limitason.” And then go back and listen to the original version on Manga. As great as reEncanto is, it’s even better as an entry point to an excellent discography. I’m just sorry it took me this long to find it.

TAEYEON – Letter to Myself

What’s the point of having a great voice? What’s the point of learning to “sing well”?

When put like that, it sounds like kind of a ridiculous question. But in the context of pop music, it’s actually seriously worth addressing. After all, ever since somebody in the ‘50s realized that you could make incredible music by writing three-minute symphonies for teenagers to sing, the actual technique hasn’t been too important. Everybody has their list of major pop stars who don’t have great technique; Madonna and Taylor Swift probably come to mind. As, of course, do any number of K-pop idols, including most of my favorites.

Which doesn’t mean that Madonna or Taylor are bad singers.11 What matters, of course, is how they make you feel; and both are extraordinarily good at getting their point across, in choosing their spots, in making their singing match the spirit of the music. In the end, we’re all here for music, right? Why should perfection of the singing matter?

In any case, that’s the kind of thing you’ll read a lot from people like me. (I’ll leave it to you to fill in exactly which traits I have in mind with “like me.”) But at this point, I have my doubts about how true that actually is in general. A lot of people aren’t here to listen to “the music” as an abstract entity, or even for the overall sound of a particular performance. They want to hear a specific person, a specific voice.

I think that’s the only way to explain why so many fans fall madly in love with the shapeless R&B and ballad tracks written to show off their favorites. I don’t just mean in K-pop: Mariah Carey obviously has great songs, but she also has a mountain of such stuff like that terrible song she did with Boyz II Men. Still, the problem is certainly endemic in K-pop; fans go gaga for tuneless junk if it means they can hear their faves give “intimate” vocal performances.12 Kyuhyun—probably the single best vocalist ever to debut in an idol group, anywhere—just released a whole damn album of this stuff.13

I’ve felt for something like the past five years that Taeyeon’s discography has been sliding in this direction. Having started out her solo career with bonafide pop songs like “Why” and the absolutely loaded debut full-length My Voice (probably in my top five K-pop albums), sometime after 2019’s stellar “Four Seasons,” her music started getting more and more muted, the album tracks tending more and more toward bland filler. For me, the nadir was last year’s To.X. The lead single is somewhat catchy—I like the post-chorus—but something just feels missing from the song. Sometimes it feels like she’s barely trying when she sings. (That’s even weirdly true when she’s wailing in a song like “Melt Away.”)

That’s the downside of great technique, after all. You can make it sound easy.

There’s something of a rivalry between Taeyeon’s and IU’s fanbases. Taeyeon’s like to call her “Certified Vocal Queen” (it’s even in her English Spotify bio), while IU’s of course want her to be Korea’s greatest singer. There’s been some amount of drama ginned up surrounding the two, although it’s mostly in good humor and the “rivalry” does seem to have cooled off in recent years. Still, the comparison seems to be a perennial source of debate.14

It’s a comparison that’s misleading at best. Not least because there is no doubt that Taeyeon is a significantly better-trained and more technically capable vocalist than IU. Within a year of debut, Taeyeon was doing a credible Whitney Houston. She makes it sound natural. By contrast, IU’s most serious attempt at doing R&B sounds like she’s pushing herself to the absolute limit.

Probably some fans do actually think that IU has amazing technique, that her three high notes in “Good Day” are some incredible feat. (For the record, they’re just E5-E♯5-F♯5.) But I think that, for more people, the appeal in hearing her sing like this is precisely that she can’t quite do it, that she makes them sound impossible. The best IU performances are perched on a knife’s edge: the Love Poem encore performances of “Dear Name” and “Love Poem” are so moving precisely because she’s pitchy, because she struggles to get through even the easy parts of the songs. The struggle is a perfect match for the mood of the two songs, for the events that colored everything on that day.

With Taeyeon it’s different. You expect polish and bravura. Even on her coffeeshop stuff like “11:11,” you can just hear the technique oozing out; in the most comparable IU songs (like “Knees”), she labors over every syllable, and you love it precisely because she can’t sing it very easily.

Of course none of this means that a capable singer can’t make a song sound effortful and emotional; I listen to opera and Ailee and Marvin Gaye, after all. It just takes a lot of, well, effort from the performer. In my favorite Taeyeon song, she has to push for pretty much the entire chorus to get the right effect. And it wouldn’t work if it were a different kind of song: it has to be intense and/or energetic, or else the singing will sound like completely over-the-top vocal display. We’ve all heard how ridiculous it sounds when that one guy (or woman) decides to really go for it on “Happy Birthday.”

With Letter to Myself, I finally feel like Taeyeon has the right kind of songs again. The title track and closer “Disaster” are her best pop songs in years: the most memorable tunes, the best beats, the strongest song structures with the most satisfying climaxes. And throughout the album, her performances just feel more committed. It might just be an artifact of the production (how closely she was miked?), but her vocals cut through significantly better on Letter to Myself than they did on To.X. They’re literally just louder (compare “Hot Mess” on Letter to “Melt Away” on To.X for a striking side-by-side), less muffled with effects, and given more room on the mix. If To.X could sound a bit like Taeyeon phoning it in, there’s no doubt that she is singing on “Letter to Myself.”

It’s not all good news; there’s still the requisite dose of blah R&B. (The fans must surely love “Strangers,” since I really hate it.) Still, this is Taeyeon’s best in years, and a really promising sign in terms of what SM Entertainment thinks works for her. If she’s the “Certified Vocal Queen,” you should really give her songs to sing. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Also liked…

Nokuthala Ngwenyama and the Takács Quartet – Flow

Annarella and Jango – Jouer

Sofie Royer – Young Girl Forever

Jamie Savan and James Dooley – The Polyphonic Cornett

Peter Perrett – The Cleansing

070 Shake – Petrichor

Asya Fateyeva and Lautten Companey – Dancing Queen: Rameau Meets ABBA (yes, really)

What I’m Reading

With Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE, Christopher Ehret has put out a concise, readable, and informative book that I’m not quite sure was intended for me. Really, I’m not exactly sure who it was intended for, but don’t let that dissuade you—it’s 175 or so pages that’ll breeze right by. Ancient Africa is a good read, and unless you’re an expert in African historical linguistics and archaeology, you’ll probably learn a lot.

I certainly did. Ehret presents compelling evidence, for instance, that iron metallurgy may have been discovered in sub-Saharan Africa as early as 2000 BCE (!). Even more strikingly, it seems to have come before bronze and copper in those areas, to the chagrin of Runescape players and Christian Jürgen Thomsens everywhere. Similarly fascinating is the discussion of African agricultural “firsts” that then diffused elsewhere; ancient Chinese staples like sorghum and millet (along with melons and donkeys) seem to have travelled a very long way indeed to the Yellow River valley. And Ehret’s account of the origins of Ancient Egypt is wonderfully thorough in how it ties Egyptian culture to southern roots (especially the Ethiopian highlands), decentering the Nile in the process. The Africa that emerges from this book is rife with innovation and crisscrossed by networks of trade and migration.

Like I said, I learned a lot. On the other hand, I often wished I could have gotten a lot more detail. There’s only so much information Ehret can give in 175 pages, and even with a reasonable apparatus of footnotes and bibliography (in which 2 out of 13 pages are taken up by Ehret’s own publications) large portions of the book have to be taken somewhat on faith.15 Ehret targets Ancient Africa squarely at “general readers,” and will thus take great pains to explain exactly why donkeys were important until the Industrial Revolution, or what archaeological terms like “relict distribution,” “chaîne opératoire,” and even “culture area” mean. That’s all nice, but there’s only so much space; I felt a little pang of despair when half a page was taken up just to show where Khartoum is on a map.

And on the other hand, when it comes to his own specialization—historical linguistics and its links to archaeology—Ehret offers a lot less hand-holding. That’s great for people like me who want to read all about reconstructed proto-Nilo–Saharan roots and what they indicate about diffusion of agricultural technologies. But it’s a bit of a funny contrast to, well, getting walked through the meaning of a relatively transparent term like “culture area.” Still, the tables and charts of linguistic phylogenies and their links to archaeology are probably the best parts of the book, even if they’re slow going. They may contrast starkly with the easygoing writing everywhere else, but don’t skip or skim them.

None of that is a particularly serious complaint. More grating is the book’s tone, which can sometimes get a little bit strident about issues where I doubt Ehret’s readership needs much persuasion. It’s good to be reminded that patriarchal societies, despite their hegemonic status in the present, were somewhat provincial if you consider the Ancient world from a global perspective. But I’d rather hear more specifics about womens’ contributions to Ancient African society and technology (which seem to have been massive!) than be somewhat repetitiously informed of that fact.

Similarly, the book takes great pains to hammer home that Africa was not a passive recipient of innovations from Mesopotamia or anywhere else, but rather an active participant—even net exporter—in the global cultural currents of the Ancient world. Great. Really great, and really well-evidenced. But I have to wonder if that’s the hill anybody needs to die on. It seems to me more likely that a certain readership would readily acknowledge Africa’s ancient contributions—“it’s where we all come from!” and all that—but still want, in some ways, to deny Africa modernity, to deny it agency in the creation of the world of the past five centuries.

But maybe both of those battles still need to be fought. I could be overoptimistic about how people generally think about Ancient Africa, to the extent that they think about it much at all. (Again optimistically, I would want to say that Ehret, who is 83 years old, might be trying to counter disciplinary trends that were more prominent thirty or forty years ago. But what do I know?)

There’s a similar impulse behind Ancient Africa’s organization. As the subtitle indicates, this is not just a book about Africa, and that’s made explicit in the final and longest chapter, which takes the material of the first five and sets it in the framework of an Africa-centric Global History of the ancient world. It’s a good idea, but the profusion of callbacks makes this chapter weirdly repetitious for the climax of such a short book. And I just wonder how much that chapter’s moral—Africa is/was global and relevant—needs to be hammered home. Especially for the kind of reader who wants to pick up a book on Ancient Africa in the first place.

I could easily be wrong, in which case this is a much-needed book that a lot of people should read. Frankly, that’s true even if I’m right. Pick it up when you see it. And look forward to learning the family tree of Niger–Congo languages along the way.

A few others:

Aeon – Extra virgin olive oil is the flavour of mechanisation

Chicago Reader – The women who made Florence Price

Chemistry World – The new signs bringing greater understanding to organic chemistry

The Dial – The Promise of Duolingo

Fandom Exile – The (Super)fan Economy

Thanks for reading, and see you again soon!

I can’t find very much about Donnie, but he doesn’t seem to have a direct family tie to Charles. His father, at any rate, is Cooper Wilson, another carver.

Is this just a Haida thing? Remember Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson?

I think; he doesn’t credit a drummer in any case.

There is of course one famous exception, a movement from a Bach concerto transcription that does get a lot of play, but that will have to wait for a different post.

The Codex Faenza is loaded with intabulations of songs; jump to the present and I’d imagine you’d find that the vast majority of new piano sheet music being produced and played consists of transcriptions of anime music and pop songs.

Tchaikovsky and Rossini are also of course better than their reputation among snobs would suggest, although I think it’s no longer fashionable to dismiss them.

For more on what makes Vivaldi tick, I will again direct you to Susan McClary.

I’m citing the Bach version everywhere; the original is in G major.

There are other parts, but they’re also just playing eighth notes.

Starting the measure on fingers 4 and 2 worked surprisingly well for me; your mileage may vary.

No comment about Saerom.

For the record, these are my faves; I’d probably be less harsh about the songs if I cared less about the performers.

“Bring It On” isn’t bad.

Ironically, among international fans, a hardcore fan of one is quite likely to be a fan of the other. (And, sadly, of Taylor Swift.)

Ehret, to be fair is reasonably clear about how speculative or grounded any given claim is.

BTW ... re the Largo in the Bach/Vivaldi ...E flat m Prelude in WTC Bk I?

BTW ... re the Largo in the Bach/Vivaldi ...E flat m Prelude in WTC Bk I?