Weeks 29 and 30: 20/22 May 2024 - Pentecost and Trinity

Plus: Thank-yous, æspa, Knut Hamsun, and more!

I’ve lumped together both sets of notes for this week: if you’re here for Wednesday’s grand finale concert, that program is linked here.

And, if you want to keep reading, please fill out the “future of the blog” form! Make your voice heard!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

I’m still catching up on all the musicians profiled in Craig Harris’s Rise Up!, but—to follow on from his fellow Ojibwe Wisconsinite Bobby Bullet—I was especially intrigued by the lengthy autobiographical piece by Paco Fralick. Sure, Fralick gives many of the clichés you’d expect—“music is in my DNA,” childhood piano lessons, shooting pool in the bar when he was too young to get everything going on around him—but also has a surprising amount of focus on Fralick’s “day job” as a dentist, what that’s meant to him, and how it influences his thinking about music. Not that an album like Letting Go sounds part-time or amateurish. “Women and Water” is a beautiful meditation on environmental destruction, “Homeless Man” a genuinely touching and sympathetic approach to its subject. But album closer “Where Were You” really takes the prize: it’s a powerful call to remember legacies of Native environmental and political activism, couched in an excellent folk-rock arrangement. If your copy of Harris’s book hasn’t arrived yet, you can read Fralick talking more about his work here.

Week 29: 20 May 2024 – “Meine Seele erhebt den Herren”: Songs of the Summer

Please save applause for the end of each set

Fugue in G minor, BWV 131a

Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält, BWV 1128

Trio after Telemann (?) in G, BWV 586

Es ist das Heil uns kommen her, BWV 638

Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten, BWV 647

Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten, BWV 691

Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten, BWV 690

Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten, BWV 642

Meine Seele erhebt den Herren, BWV 648

Fugue on the Magnificat, BWV 733

What a weird piece. Even if you don’t remember how the BWV catalogue is organized (but you, a faithful reader from the start, surely remember), the low number “131” might have jumped out to you. And what’s up with the “a”?

BWV 1–200 or so are all the pieces we now call cantatas (even if Bach mostly didn’t). Alphabetic numberings like “-a” signal pieces that are related in some way, especially early versions and transcriptions. See where this is going now? Here’s the original (19:42):

And here’s the organ version:

It sounds a little bit weird on organ, and maybe not just because the arranger (doubtfully Bach) was a little clumsy. For whatever reason, the harmonic language of Bach’s early vocal works (this one is from the Mühlhausen period, 1707–8) was often somewhat distinct from how he wrote for keyboards, perhaps thanks to the kinds of stereotyped progressions that are natural or ingrained for keyboard players. So this fugue oddly doesn’t sound like an organ piece, even with a pretty idiomatic arrangement. Potentially a warning sign for those of us who would like to steal more fugues from the cantatas and motets—but hey, if this arranger could do it…

And then we have another weird BWV number. It used to be that 1080 was far as the catalogue went; now 1128 is more or less the limit, with most of the numbers beyond that going to pieces that are no longer extant. So how did this piece come to get the “last” BWV number?

“Wo Gott der Herr” was only published in 2008, because the main surviving manuscript copy of it (an 1877 copy of a source once owned by W.F. Bach) only resurfaced at an auction then. You can read the whole (surprisingly boring) story here.

It’s possible that the piece slipped through the cracks in part because it’s so atypical for Bach. Even more than “Ein feste Burg” or the BWV 718 “Christ lag,” this is a faithful representative of the slow, gloriously meandering chorale fantasia style exemplified by Buxtehude’s Nun freut euch and (no apologies for the self-promotion) Bruhns’s Nun komm. It therefore seems likely that “Wo Gott der Herr” is a pretty early piece, although it’s much better organized and more self-assured than any of the Neumeister Chorales. Even if (or maybe because?) it’s a lot shorter than its precedents, BWV 1128 can hang with the best of them.

I hope the whiplash isn’t too strong going from that to the G-major Trio BWV 586. If “Wo Gott der Herr” could plausibly pass itself off as a piece by Buxtehude, BWV 586 genuinely has passed itself off as a potential piece by Telemann, which is to say a piece in a style almost half a century later. There’s no evidence for that attribution—we just have one copy that says Bach—but it’s definitely true that there are some Telemann-isms throughout the piece, and not very many Bach-isms. (The harmonically bizarre measures that end each half don’t really sound like either composer.) The organ writing is somewhat like the “Bach circle” arrangements BWV 1039b and BWV 585, with rhythmically simple but astoundingly awkward pedal parts. So yeah, it’s unlikely that this is Bach’s arrangement, or Bach’s piece. But who are we to say? It’s at least got its interesting moments, and it’s still pretty fun. Better than a lot of authentic Bach can say.

It’s a little surprising that Bach only has one organ version of the indispensable all-purpose choral “Es ist das Heil”; he used it in a half-dozen cantatas (hello, BWV 9!), and practically every German Baroque organ composer had something to say about this tune. Matthias Weckmann was inspired by it to write a truly mammoth set of variations (Verse 6 usually takes over 11 minutes by itself). But Bach just left one Orgelbüchlein chorale. It’s a perfectly standard specimen from the collection: yet again, the tune is on top in long notes, with running sixteenths under and a walking eighth-note bassline. And it’s even a good piece, making great use of the chorale’s harmonic quirks (♭7 in the opening phrase??). Still, I guess Bach’s attention was elsewhere.

Oh, that’s where his attention was. Bach really liked “Wer nur den lieben Gott,” which shows up in not only these four organ pieces, but also ten cantatas. And honestly: fair! It’s extremely catchy, with a very clear harmonic and rhythmic profile (the triple-time version is great) and an excellent build-up to and away from its high point. Each of these settings makes the tune clearly audible, but all in different ways.

BWV 647 is one of the Schübler Chorales, which is to say that it’s an arrangement from one of those ten cantatas. (BWV 93 for those both dying to know and incapable of using Google.) It’s a sweet piece, if desperately awkward for the hands; at least the tune sings out nicely in the pedals. There’s plenty of rhythmic interest, and—like the other Schübler Chorales—the instrumental origins of the piece are quite audible. (In case it’s not clear, that’s a plus in my book.)

The other “Wer nur” settings are organ music through and through. BWV 691 is a very pretty take on the tune in “ornamented chorale,” or even “sacred song” style, with an unusually simple and tuneful left-hand accompaniment. BWV 690, is an Orgelbüchlein-style layer cake, with the triple-time version of the tune placed above flowing sixteenths. (BWV 690 is also one of those two-for-one chorales that ends with a full verse of the hymn notated in figured bass.) And finally BWV 642 actually is an Orgelbüchlein chorale, in the same old format, albeit with a jaunty long-short-short figure animating the accompaniment. This was the first Orgelbüchlein chorale I learned, and it’s the last one we’ll hear for the series.

We’ll also close out the Schübler collection, with the truly unique “Mein Seele erhebt den Herren.” This intense, chromatic, expressive movement is—like everything else in the collection—drawn from a cantata, in this case of the same name. (The “German Magnificat” BWV 10.) There are some slight changes made in the organ arrangement but nothing too drastic—and the result is pretty fearsome, with one of Bach’s weirdest and least idiomatic pedal parts coupled to equally stretchy and uncomfortable writing for the hands. At least it sounds good.

“German Magnificat” might have clued you in for why I paired these last two pieces. (For fans of Bach’s Latin Magnificat: this is the same tonus peregrinus tune that the oboes play in “Suscepit Israel.”) Like BWV 1128, the Fugue on the Magnificat falls in line with a very long and old-fashioned organ tradition; Pachelbel wrote something like 100 of these things by himself. That said, this piece is a lot more ambitious—simply bigger—than any of its models, sounding instead more like one of the old-style fugues that Bach paired with, e.g., the “Dorian” Toccata, the F-major Toccata, or the B-flat Prelude BWV 545b/i.

But in some ways it only sounds like one of those pieces. This is a piece in strict style, with all the trappings of counterpoint, but it’s not really a fugue. The Magnificat theme (in long notes at the beginning) comes in and out, sometimes in imitation; and a whole bunch of other themes play around it, in imitation that follows varying degrees of strictness. But for the first three pages there’s no consistency to it—the piece drifts in and out of fugue-dom in a way that’s more typical for Handel than for Bach (or Pachelbel for that matter). It’s only when the pedals enter with the tune near the end that the rest of the voices begin to stick to one approach. The harmony’s a little funny in this piece too (because the tune begins in one key and ends in another). From weird fugues we came, and unto weird fugues we shall return.

Week 30: 22 May 2024 – “Komm, Heiliger Geist”: Pentecost and Trinity

Please save applause for the end of each set

Fantasia super Komm, Heiliger Geist, BWV 651

Komm, heiliger Geist, BWV 652

Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit, BWV 669

Christe, aller Welt Trost, BWV 670

Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist, BWV 671

Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit, BWV 672

Christe, aller Welt Trost, BWV 673

Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist, BWV 674

Komm, Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist, BWV 667

I may not have planned this series perfectly (there have been a few calendar oopsies and some lumpy programming), but I was very excited when I initially mapped it out and saw that it would wrap up with the end of the “Life of Christ” season and the beginning of the long stretch of Ordinary Time that covers almost half the calendar. Basically all of the liturgical landmarks were in the bag. And, best of all, the final concert would coincide with Pentecost and Trinity Sunday.

That’s because I really like this music. I like “Komm, Heiliger Geist” and “Komm, Gott Schöpfer” so much that I’ve planned whole Pentecost-themed recitals around them before. (If you can translate from German to Latin, you now know why I decided to arrange the Dunstaple “Veni Creator / Veni Sancte” for organ.) And, from a certain perspective, it’s a ready-made recital: Bach chose “Komm Heiliger Geist” to open his “greatest-hits” chorale fantasy compilation (the “Great Eighteen”), and the collection ends with “Komm, Gott Schöpfer.” These pieces are just perfect bookends—even if Bach didn’t copy out this version of “Komm, Gott Schöpfer,” and potentially did not intend it for that position.

Bach had to have known that the “Komm, Heiliger Geist” fantasy is a killer opener. There’s nothing else like it in his or anybody else’s organ works: essentially, the piece blends “free” Prelude or Toccata style with chorale fantasy form. So, the beginning sounds a lot like how BWV 545 begins, or even some Well-Tempered Clavier preludes, except that the upward-rushing sixteenth notes might, in this context, evoke the Pentecostal wind of the Holy Spirit.1 By measure 4 those sixteenths have lofted you all the way up to the top of the keyboard; as you come tumbling down, the ground shifts beneath you. The long held note in the pedal suddenly climbs up to a C, and a tune begins to sound out underneath the rush of notes in the hands.

And that’s pretty much how it goes for the rest of the piece. You’d think it would get boring hearing exactly the same motivic material manipulated in the hands, with phrases of the tune strewn in almost randomly by the feet. But it never gets old. Maybe chalk that up to subtle forms of variety—I love the hands-only episodes that use “sighing” motives à la Well-Tempered Book II in F minor. Maybe credit Bach’s careful harmonic planning, which uses steadily harsher minor keys toward the middle and relaxes into the subdominant at the end. But I think most of all just credit the material. It might be made out of musical basics—ascending arpeggios are not a new trick—but so is Robert White’s guitar part for “My Girl.” When you come up with a riff this good, you can kind of just let it play for five minutes.

I said above that I was excited at the prospect of closing things out with a Pentecost/Trinity concert—all killer no filler! But then I remembered the other “Komm, Heiliger Geist.”

Is that too harsh? I’m sorry: I just have nothing nice to say about this piece. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Bach’s second-longest organ chorale, just like his biggest organ piece, is practically never played: it’s almost unlistenably boring. At least you can hypothesize that “Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir” is a decorated hymn accompaniment (I have some reservations); the second “Komm, Heiliger Geist” could not possibly serve that purpose, and yet here it is, clocking in at 200 measures and 9 minutes.

What’s wrong with this piece? In some ways, it seems like it should just be a souped-up version of “Schmücke dich,” of “An Wasserflüssen Babylon,” of the penultimate “Sei gegrüsset” variation: it’s another one of those long, dreamy, pretty sarabande settings of a chorale tune. And yet. This piece has absolutely none of the charm that any of those three bring to the table. Each of the other pieces uses consistent, well-defined musical motives, lucid rhythmic patterns, and engaging, equally clear-cut harmonies. “Komm, Heiliger Geist” No.2 does precisely none of that. It’s almost Brahmsian in its attempt to avoid anything catchy, offering practically nothing remarkable or varied until it speeds up at the very end. (Even the closing passage is pretty rote.) It’s very cool that Bach could write two such diametrically opposed settings of “Komm, Heiliger Geist”: flats vs. sharps, 3/4 vs. 4/4, fast vs. slow, ornamented vs plain, tune on top vs. on the bottom. I just wish that he hadn’t also made “musical interest” one of the points of contrast.

Moving now to the “Trinity” theme, we now get the three big chorales of the German Kyrie from Clavierübung III, pieces that amply prove that “old-fashioned” does not necessarily equate to “austere” or “boring” Bach. All three of these pieces are essentially three-voice fugues on a version of the chorale tune, with the tune itself played in long notes at the top (Kyrie I), in the middle (Christe), or in the bass (Kyrie II). The rhythms and polyphonic textures are certainly old-school, matching the stile antico material that Bach brought in for the B-minor Mass (Kyrie II, Gratias, Credo, Confiteor). But that doesn’t preclude Bach from thinking about harmony if he wants to. Listen, for instance, to how the first phrase of the first Kyrie moves heartbreakingly to minor, while the second phrase brings the music back to major—a symmetry that’s then repeated, in more elaborate form by the third and fourth phrases. Similarly, the Christe relishes in harmonizing its repeated phrases (lines 1 and 2 are almost the same as 3 and 4) in completely different ways, and keeps things lively with a fairly athletic sense of rhythm.

And then there’s the third Kyrie. Written in a gloriously thick five-part texture (since it’s in the same key, it’s hard for this piece to avoid using some of the tricks you already heard in the “St. Anne” Fugue), this piece is built on a tune facing off against the upside-down version of itself:

When it’s all massed together, the resulting pile-ups sound gigantic, like planets colliding. And what Bach does with the harmonies in the final line is truly terrifying:

OK, I guess that doesn’t look like much on the page. You’ll just have to hear for yourself on Wednesday: when that first G-flat enters, it sounds like the first trumpet of the Apocalypse.

One more spin around the Trinity to close out the Clavierübung III collection. And this triptych probably exemplifies Bach’s obsession with the number 3 when putting the book together. The time signatures of 3/4, 6/8, and 9/8 traverse the gamut of triple/compound possibilities, gaining three beats per measure in each piece to culminate with 3✕3 eighths in the Kyrie II.

It might be stretching things too far to note that all three of these pieces constantly have the parts play in parallel thirds. Still, even if that particular use of a “three” isn’t numerologically motivated, it does help give these chorales their character: they’re all sweet, smooth, danceable, and lovely—clearly designed to work in contrast too (palette cleanser?) the mammoth pedaliter chorales that precede them. It’s nice not to have everything on the program working at such monstrous scale and/or volume.

Anyway, to finish off the series: a monstrously-proportioned, very loud piece. Actually, “Komm, Gott, Schöpfer” (I assume the rest of the hymn is sung in praise of commas) is not all that long, since it’s essentially a double Orgelbüchlein chorale. I mean that literally: the first half of the piece is just BWV 631 from the Orgelbüchlein itself, with a second variation on the tune tacked on afterward. The first time around, the pedal, unforgettably, plays on all the weakest beats, every third eighth note of the 12/8 measures; it sounds like a jig danced by somebody with a third-degree ankle sprain. But as that verse ends, the music completely shifts character, getting caught in an upward rush of whirling sixteenths. Then the tune flips from the soprano to the bass: so, instead of that limping dance, we now have a rock-solid foundation for the musical firestorm above. Bach may not have written this ending into his book of organ chorales, but his student Altnikol knew what he was doing. And I’m happy to take his idea and use it to end this series.

Thank You!

I’ve already given my Oscars-style all-encompassing thank-yous at the end of this series’s FAQ,2 but indulge me if I make one more go-round now that Bach at Bond is wrapping up.

Having passed on actually thanking the Rockefeller Chapel staff individually the first time around (Bond has no dedicated staff), let me make amends and do that now. Everybody in charge has been just awesome: Deans Charles and Cunningham have been warmly supportive from beginning to end, and the series definitely wouldn’t have happened without the enthusiasm of the music staff, especially James Kallembach and Tom Weisflog. The administrative and events staff—Matthew Dean, Irene Claude, Mike Boyman, and Ana West—put a massive amount of effort into actually organizing the logistics behind the series: booking spaces, sending out publicity, printing posters (thanks to Gearóid Burke for a great design!), and generally putting the Chapel’s full weight behind Bach at Bond. I can’t begin to say how grateful I am that they made such an investment of time and energy, such a commitment to my harebrained idea.

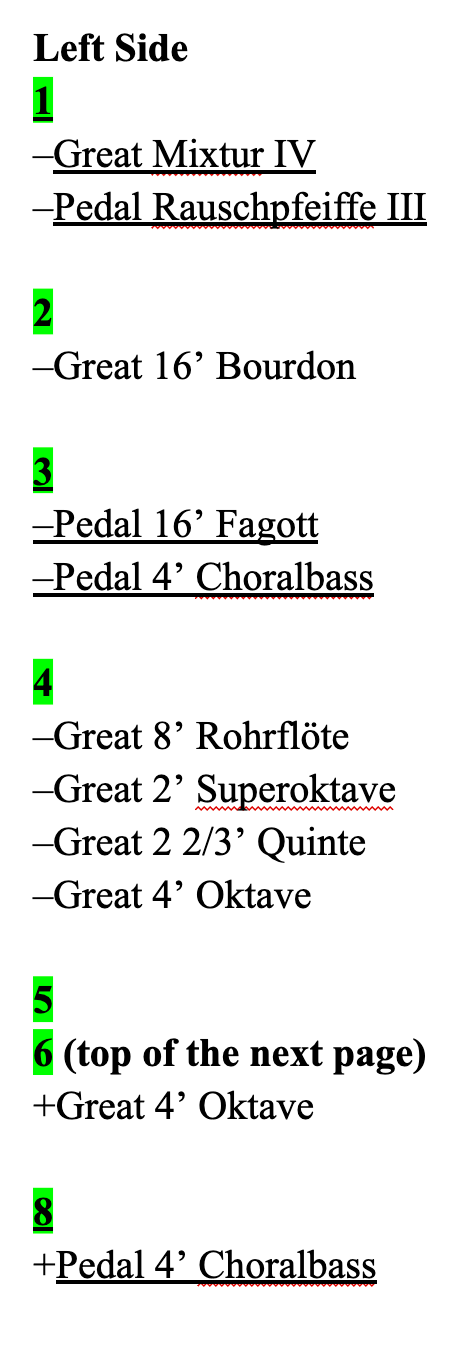

I’ve already named Irene, Mike, and Ana, but I do also want to single them (and Hannah) out for their on-the-ground work every week: taking headcounts, printing the flyers with QR codes, rearranging all of the chairs in the chapel, setting out the signboard, and generally readying the space for the concerts. I basically didn’t have to do anything except practice and show up, and that’s a rare privilege. Mike and Irene are also excellent pageturners—as are Caleb Herrmann and Alex Tripp, who acquitted themselves spectacularly in two rock-solid appearances as stop-pullers. Imagine showing up when a friend called in a favor—“it’s pretty chill, don’t worry!”—only to be handed nine pages of this:

After that Passacaglia performance (you did figure out that these are registrations for the Passacaglia, didn’t you?), when I gave Alex and Caleb their own round of applause, a slightly confused audience member asked which of us three had played what parts. Truthfully, she wasn’t so far off the mark.

Alright, it’s time to get cheesy: thanks most of all to you, even if—based on the questions I get at the concerts—it seems like most of the people who actually read this far aren’t recital attendees. (Not just because I get a couple hundred readers per post and attendance better measured in the dozens.) A huge shoutout to the shocking number of people (ten or so) who’ve made it to 25+ recitals, including the crew who sent me a Christmas card (!). But also shoutout to the far more sensible—and much, much, more numerous—crowd who dipped in for one or two recitals. I loved hearing that Bach at Bond became part of people’s campus tours or holiday plans. One of my hopes for the series was to present one of those “well, it’s always there if I want it” musical offerings (pun not intended), and to the extent that people drifted in and out, I succeeded.

And don’t get me wrong: thanks also to those of you who have only been reading, whether due to circumstance (can’t travel across the country; can’t take time off work for a concert at this admittedly bizarre and inconvenient timeslot), general lack of desire to go out, or actual apathy toward Bach’s music (if that’s you: the K-pop feature this week is æspa; look forward to it). It’s been cool hearing people who are significantly better and more trained writers say (for some reason always the exact sentence?) “I love your Substack!”, regardless of whether or not I’ve seen them at the recitals. To the extent that I regret the split between recital and blog audiences, it’s because I worry that some of the recital Bach-a-holics aren’t thinking about the genuinely thorny issues that Bach and his legacy have left for us. It would be a shame if anybody came out of this whole experience simply thinking “Man, Bach was so great!” I certainly didn’t.

Anyway, if you have been reading so far, thanks again, and please do fill out the “future of the blog” form. I have enough responses so far to justify some kind of follow-up, but the exact nature of that writing is in the end going to be up to you. It takes a minute or less!

What I’m Listening To

Brad Mehldau – Après Fauré

I know it’s a gimmick. “Experienced jazz hand goes Classical” (let’s be real, it’s very often specifically “White jazz pianist”) is a very old trick now, and the results are decidedly mixed. I really don’t want to hear any more of Keith Jarrett playing Bach, and I don’t want to hear Ethan Iverson write another piano sonata. Whether or not the musicians themselves intend these records to be a form of cultural legitimation—“let me prove my musicianship by giving you DEAD GERMANS”—that has to be part of the marketing calculus. Ick.

I think part of the problem is that there may be an unspoken expectation that a jazz pianist playing BACH will come at the music with a “completely fresh” perspective, that it’ll sound like a space alien’s novel interpretations. Unfortunately for this idea, most of the relevant musicians had classical training, often extensive training. Their Bach is basically post-Gould, often without years of Classical-specific concert experience to season their playing. Yawn.

That said, there is something to be said for a jazz take on repertoire that’s a little closer to these musicians’ bread-and-butter harmonic language. When Brad Mehldau intersperses his own improvisations in his Bach CDs—a new one was just released this week as well, but I don’t want to talk about it—it’s harmonically, rhythmically, and gesturally jarring, a violent contrast. But on a disk of Fauré? Mehldau at his most conservative is already practically playing Fauré. The first three of his new pieces on this recording (the ones with the Frenchy titles) demonstrate an incredibly sophisticated and subtle understanding of what makes Fauré’s harmony tick, of his rhythmic and melodic style, of how he likes to put phrases together. It’s almost spooky.

To be sure, Mehldau’s Fauré itself can sometimes sound a little strange (although I want to chalk some of that up to the piano and recording technicians): everything is extremely clear and precise, not “dry” per se, but weirdly well-lit. The rhythms can be etched a little too crisply, and his sense of swing is, well, pretty different from what French musicians would do. Still, it’s pretty nice playing, and certainly illuminates what he’s doing on his original compositions. I think I’d still rather hear another Art of the Trio album, but if Mehldau’s going to keep going in this direction, at least let him try more music like this. And no need to pair it with After Bach III next time—isn’t there enough Bach in the world already?3

睡後故事 – 睡後故事

I could just be hypersensitive. I spent almost my entire first listen to this album basically white-knuckling it, waiting for the other shoe to drop as this gentle indie folk would surely, inevitably lapse into kitsch. Acoustic guitar, sleepy vocals, clarinet, and accordion? There’s no way this wasn’t eventually going to turn into “Disney movie set in Paris” crap à la BIBI or Mr Miss 先生小. And Shui Hou Gu Shi do constantly ride the line, keeping almost the entire record on a knife’s edge: oversentimentality is so close on tracks like “Extending a Hand to Grab a Star 伸出手抓住星星.”

Miraculously, they never fall into the trap. It’s partly a matter of extremely judicious bass playing from Donghee Lee, of sharp percussion choices from Sayun Chang, of unconventional accordion playing from Huang Chieh (the Radiohead-esque minimalist interlude that comes about 2 minutes into the title track is great), of rhythmic surprises and delicate vocal inflections. But I also think it’s about what they do with their material. There’s plenty of straightforward and even sugary stuff on this album, but Shui Hou Gu Shi never let anything sit long enough to turn saccharine or cheesy. The longer songs (title track; instrumental “Anonymous 無名氏”; late-album highlight “A Big Rock in the River 河中大石”) constantly evolve, letting ideas grow, develop, and subside.

And man this album is gorgeous.

(I found this album through Mando Gap) justly identifies “Characters with the “Water” radical 水字旁” as the biggest highlight. It’s Shui Hou Gu Shi at their freest, sonically richest, and possibly most original: I’m sure everything is actually quite carefully rehearsed and assembled, but it really does just sound like a free collective improvisation on images and feelings of water. It was during this track that I finally exhaled on my first go-round. If they can do this, they’re not going to subject me to Disneyland Paris. And after the fear subsided, I could finally hear gorgeous tunes like “Thorns 刺” for what they are: this is just excellent, smart music-making. Even with the accordion.4Ballaké Sissoko and Derek Gripper – Ballaké Sissoko & Derek Gripper

Maybe I’m a sucker. (I am aware that I have now begun three consecutive sections with the same exact kind of disclaimer.) I like Ballaké Sissoko’s music freely and indiscriminately. It doesn’t matter, for instance, who he’s collaborating with: New Ancient Strings with fellow kora player (and crossover artist) Toumani Diabaté, Musique de Nuit with cellist Vincent Ségal, and especially “what if ALL the plucks?” supergroup 3MA’s self-titled album, which matches Sissoko with oud player Driss El Maloumi and valiha player Rajery—all are wonderful. Yes, loving all of these records places me firmly in “world music fan” stereotype territory. I kind of don’t care. Look: the results really are that good.

Now Sissoko is back with Derek Gripper in what I guess we should call the “Ry Cooder endowed chair in White dude world music guitarist.” Somewhat like Cooder, Gripper is good enough to overcome most of my skepticism, and good in particular at meshing his sound with Sissoko’s. They genuinely sound like they’re having a blast playing off of each other, each maintaining the characteristic musical gestures of their instruments while messing around with the large common ground between them. Sometimes that play is sonic: there are some really cool sounds stemming from extended techniques on tracks like “Koortjie.” Other times it’s rhythmic, producing the the fog of strumming at the beginning of “Moss on the Mountain.” It’s just nice to hear two musicians really go at it together like this, and Sissoko is always good for that. I’m sure I’ll love his next album too, whatever it is.

æspa – “Supernova”

You have to feel for IVE. OK, actually, you really don’t; they’re stupefyingly successful, having exceeded even æspa’s chart performance and sales, and—unlike, say, LE SSERAFIM or ILLIT—they’re relatively controversy-free. If your group’s most memorable drama is about how one of your members ate a strawberry, then you’re doing pretty well. (And they’re already on the path to victory against more serious forms of defamation.)

Still. You have to imagine that Starship Entertainment thought they had this week in the bag. It was a great idea: extend IVE SWITCH’s promotional period by releasing the music video for the second single a couple weeks late. And make that video pop, giving it a high-concept plot about fighting evil counterparts of IVE for control of some kind of magic wand:5

But it’s hard to compete on the terrain of “high concept” when you’re facing æspa.

I promise to eventually talk about the actual song (æspa’s; I already said my piece about diet “Kitsch” “Accendio” a couple weeks ago), especially since I think “Supernova” kicks ass. But come on. Given what æspa’s put out this week, music is the absolute last thing anybody wants to talk about.

With the exception of aggressively normie cut “Live My Life” (it’s hard to tell from these teaser videos, but I suspect I’ll love this song), the track videos that SM Entertainment has been releasing for æspa’s upcoming full-length are maybe the most delightfully unhinged things I’ve ever seen a purportedly mainstream, non-Japanese music act put out.6

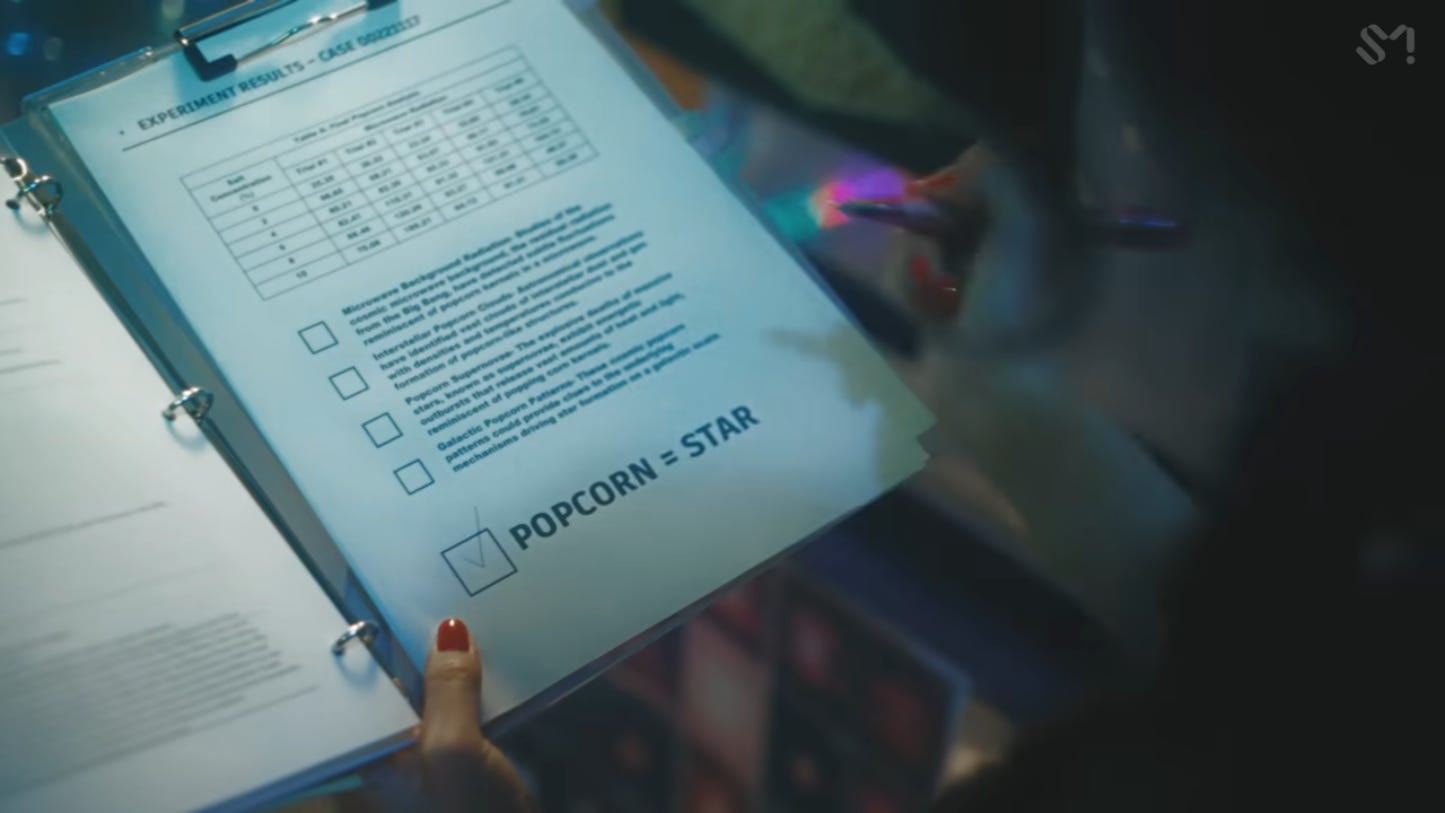

Seriously. Even 100 gecs videos are conventional and boring by comparison. The video for “Money Machine” may be deep fried to hell and back, but it basically just shows gecs singing and dancing to the song. Meanwhile, The “Long Chat (#♥)” video is loosely edited to the music, but instead of having them sing and dance, we get, um, “catgirl aeronautical engineer discovers that meteorites are anthropomorphic popcorn”:7

And there is nothing about any of this in the lyrics (at least during these snippets of the song). Not even a metaphor about falling or stars or “science” or…corn. Somebody at SM must have just had this insane idea (or they all put their ideas in a blender?) and decided to pair it with any old song.

At least the “Licorice” video is vaguely on-topic:

No, the lyrics aren’t about the Power Rangers battling evil mint chocolate chip ice cream, but at least they’re about a complicated relationship to “food” (as a metaphor). On the other hand: please don’t ask me what’s happening at the end of the video. I have no clue either.

And then we have “Supernova” itself. A lot of the visuals and edits are funny enough by themselves:

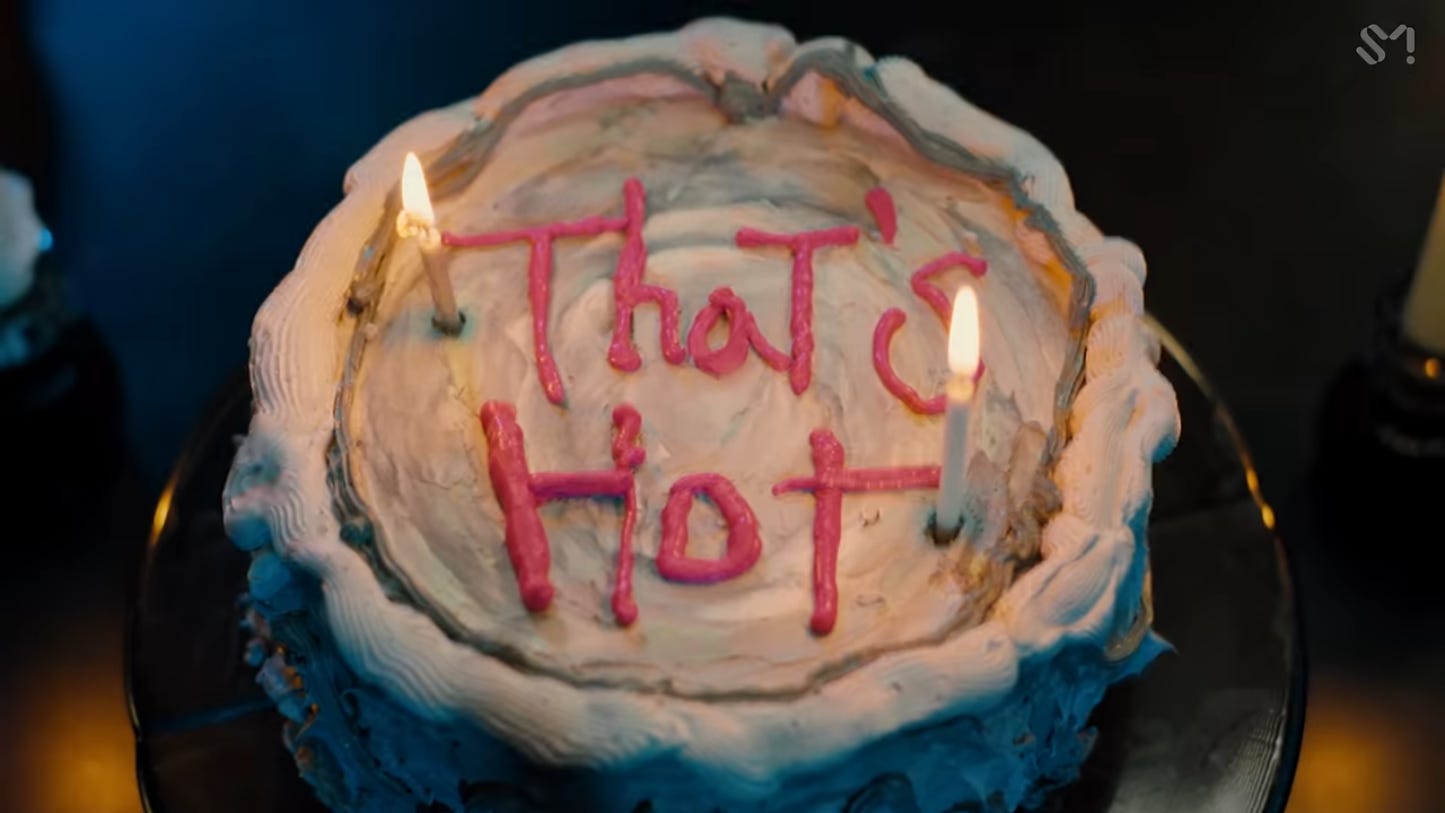

But others are pure references to in-jokes and memes in the æspa fandom, like Giselle’s favorite Paris Hilton quote:

And Karina headbutting the camera:

In other words, basically the entire video is played for laughs, despite having “badass” music and themes (“teen aliens with superpowers”—don’t ask me what that has to do with virtual avatars or whatever; I already wrote my bit about æspa lore). It’s not quite “Catallena,” but it’s the funniest branding a big K-pop group has gone for in a long time.

It’s also a bit of a left turn for æspa, who have mostly leaned in to the “badass” part on their prior title tracks. Not that a track like “Girls” isn’t in some ways utterly ridiculous—remember that not only did SM make Giselle rap about the metaverse, but they also forced her to try to rhyme “world” and “heart”8—but it’s not knowingly silly.

But as people in the world? æspa have as silly of a public image as you could possibly imagine. Just look at these dorks (in the back):9

Is the “Supernova” video an attempt to bring the persona closer to the performers?

If so, I’m not sure the song itself is trying to do the same work. Instead, it picks up where all of their prior singles have left off. One-chord-esque structure just like “Drama.” 80s synth samples (Afrika Bambaataa lives!) just like “Next Level.” A chorus built around a repeated consonant just like “Savage.” And, just like “Spicy,” this is a song that mainly serves jumbo-size glottal stops with an extra-large basket of vocal fry on the side.10

Maybe the biggest difference from æspa’s previous singles is that there’s almost nothing that I would call rapping on “Supernova.” For that matter, there’s not a ton of singing either. Instead, the majority of the song is chanted or sung-spoken. Those moments can be more or less definite in terms of pitch: the lines in the prechoruses that end in “Ah oh ay” mostly center around D♯s and F♯s (an uncanny clash with the E-F-D bassline), and the “Bring the light of a dying star” line in the chorus is definitely tracing a fifth down from B to E. (“Su-su-su-supernova” is doing something similar at a lower pitch level.) But the rest of it? It’s neither fish nor fowl, getting by on almost pure attitude.

The craziest thing (yes, including the video) about this song is that it actually works. Aside from maybe “Spicy” (a polarizing release), this is easily æspa’s best single to date, and—uniquely among æspa tracks—quickly seems to have attained critical consensus as a great song. How did producers Kenzie and Dem Jointz pull it off?

There are some basic and maybe obvious answers. Killer backings, for sure. Great vocal performances, if mostly of nontraditional kinds. And all of the hooks are definitely addictive in terms of rhythm. But I feel like there’s something more going on here.

Chanted and sung-spoken hooks like this may be a high-risk, high-reward proposition. (That would help explain why SM has done so many of them for NCT.) Obviously, when done wrong, this kind of thing is just plain annoying, and even unmusical. But when it works, like in the chorus of f(x)’s “Airplane” (and we know that Karina loves f(x)), sing-talk lets songwriters emphasize a very simple rhythmic pattern that might not fit any kind of good melodic hook, and which would be too slow and sparse to fit into any rapper’s flow. It also sounds distinctive, given that most music obviously isn’t like this (although if you keep coming back to the well like NCT…).

And finally—we had to get back to “concept” at some point—chanting and sing-talking is a pretty good match for music by “aliens” or “AI” or “from the metaverse” or whatever SM decides æspa is about next. Especially when it features effects like that F♯-D♯/F-D clash (which might just be unbearably harsh if the notes were actually sung), “Supernova” is marked by vocalization that’s just shy of singing, sounds that are just shy of pop, music that’s not quite music. The result is spectacular. Or what I really mean is:

Also liked…

How To Dress Well – I Am Toward You

Troy Roberts with Paul Bollenback, John Pattitucci, and Jimmy Macbride – Green Lights

Radizi – Cal y cemento

Wadada Leo Smith and Amina Claudine Meyers – Central Park’s Mosaic of Reservoirs, Lakes, Paths, and Gardens

Antonello Manacorda and Kammerakademie Potsdam – Beethoven: The Complete Symphonies (6, 9, and some parts of 5 are highlights)

Without necessarily giving it an endorsement, I can’t resist noting that the same conductor has also given us this in the same week:

Antonello Manacorda and Frankfurter Oper – Meyerbeer: L’africaine

What I’m Reading

Oxford World’s Classics has recently begun releasing new translations of the works of Knut Hamsun, and that seemed as good an occasion as any to give Pan a try. I didn’t know what I was in for.

Well, I knew that Pan has a “rural” setting (as opposed to the citybound Hunger), and that it’s some kind of tragic love story. That’s all true, but it’s not a particularly good indication of what the novel is like. Really, it’s almost as intensely disturbing of a psychic character study as Hunger, and the “love story” aspect of it is just about as unromantic as it could possibly be. (For starters, Glahn, the narrator, splits his time between at least three women, and treats none of them remotely well.) The natural description is beautiful, poetically written and minutely observed—but it’s also curdled by being given through the perspective of Glahn, a hunter and soldier. Oxford emphasizes on their website that Glahn’s “faithful dog” Aesop is a main character in the story; what they don’t tell you (no spoilers: this is revealed on page 2 of the book) is that Glahn shoots Aesop out of pure spite at the novel’s climax.

That sounds pretty unpleasant, and it is a somewhat gritty read—but, unlike Hunger, it’s tempered by the setting and the plot’s romantic moments (such as they are). And Pan is also a gripping book, a real page-turner that has both a sense of inexorability and moments of real shock. The “mythic” and dream-like incursions are really fantastic, as is the nature writing; on a more granular level, the writing is well-calibrated to reveal information at a variety of tempos, and the prose, at least as Terence Cave translates it, is quite punchy. Cave, as has been the trend in English translation for a few decades now, tries to find English equivalents for what sounds odd about Hamsun’s Norwegian. I couldn’t tell you if he’s actually faithful to the original, but at least the resulting run-on sentences, comma-spliced to oblivion, are excellent reflections of Glahn’s fractured psyche.

Normally I would barely even care to comment on critical apparatus for a book like this—you kind of just expect it to be a pretty good biographical sketch, summary, and maybe discussion of some of the symbolic or structural keys that help unlock the novel. Tore Rem’s introduction sort of does that, but—astoundingly—completely sidesteps the only biographical detail that most of us would be interested in hearing discussed: Hamsun’s outright love of Hitler.11 Maybe Rem is sick of this subject, having written a whole book about it. And I get that almost everything “literary” that anybody cares about by Hamsun is from well before the Nazis’ rise: like most Nobel laureates not named Yeats or Mann, all of his reputation-making work is from before he won the prize in 1920, with Pan in particular having been published in 1894.

But this isn’t even a case where an author’s repugnant later views are easily separable from what they thought when they were writing the “good stuff”; Hamsun was a cheerfully open bigot his whole life. This book’s protagonist genuinely hates and is terrified of women, and it would have been awfully nice to see some attempt to—well, first to just acknowledge that, but also to try to put that in conversation Hamsun’s own views on women. Pan reads like the rantings of a madman, but I’d love to know how much of that is the author just letting down his own guard.

I guess that all sounds like a bunch of reasons not to read this book, and I don’t blame anybody who gives Hamsun’s work a pass. Obviously I do still think it’s worth reading, but I don’t love OUP/Rem’s attempt to make that value entirely consist in Pan’s literary merit (as a “monument”). I mean, you can definitely read it profitably that way, but it’s also very much worth considering as a “document” of the, well, tortured thinking that gave rise to the abominations of Europe’s twentieth century. Pan is not the most “pleasurable” book of all time, but I’m very glad I read it.

Fourteen East – Ticketmaster May Not Be the Only Culprit in the Rise of Concert Ticket Prices

Chemistry World – Davy notebook project paints complicated picture of influential chemist

Bloomberg CityLab – Can the $8.7 Billion Demolition Industry Get a Green Makeover?

Hakai – Not Too Wet To Burn

FanGraphs – What It’s Like To Be a Beat Writer

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it this week!

It will surprise nobody to hear that I think organists by and large miss the point by playing this piece too slowly—although they used to take it at a great tempo.

Please clap and admire my witty punchline.

Note that Hong links the accordion’s presence to old-school nakasi music.

No comment about whether or not having Gaeul be the protagonist was a good idea.

Yes, not even “Can’t Love You Anymore.”

Wait, why is Cornelius EATING popcorn?? How deep does this thing go??

Or worse, rhyming “honestly” with “honestly” on “Spicy.”

Winter was absent from filming due to some combination of smoke inhalation and caution around her pneumothorax.

The only reference I saw was in the book’s Chronology.

'erhebt' (den Herren) ....an innocent word from Luther to Bach's time, about to undergo an apotheosis ...'erhaben' is a key word in the 1750's and 60's thanks to the discovery of Shaftesbury and Burke by the likes of Baumgarten, Lessing, Michaelis, and Mendelssohn...then onto Kant...But then 'aufheben' comes along around 1800 in Hegel. More a symptom than a cause of the many changes going on...but interesting...no wonder Bach seemed so ancient by Beethoven's time.

yasher koach...wish I could be there for the grand finale...

I guess we have to hope that IU does not become a trio with someone like David Oh...