Week 7: 13 November 2023 – Trio Sonata No.5 and Trinity 24

Plus: the Reneker Organ, a surprise from Jungkook, an introduction to Kunqu, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

This week, I’ve been digging back into the discography of Keith Secola (Anishinaabe Ojibwe)—not exactly an underground name, but there’s more to his work than “NDN Kars.” The Wild Band of Indians and Circle albums as a whole rock pretty hard, while of course always staying on-message.

Week 7: 13 November 2023 – Trio Sonata No.5 and Trinity 24

Please save applause for the end of each set

Prelude in G, BWV 568

Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig, BWV 644

Trio Sonata No. 5 in C, BWV 529

Aria in F, BWV 587 (after Couperin, Les Nations)

Prelude in B-flat, BWV 545b

Another Prelude without a fugue, following a somewhat similar plan to the A-minor prelude from week 2: lots of scales, lots of repeating sequences, lots of drama. But this Prelude is a bit more relaxed, breaking up the busy passages with showstopping, slower chords. And it certainly has a lot more fun with the pedal writing, with long runs scrambling up and down the whole pedalboard. There’s really not too much to say about this piece: better to match it by staying short and sweet.

Speaking of short (but maybe not sweet): the Lutheran conception of life. I’ve gone back and forth on how to play “Ach wie nichtig.” Certainly, it’s possible to make it sound “trivial” and “fleeting” by skimming through it on flutes—and I even like how that works. But I’ve also been experimenting with giving it a bit more of a grander sound:

In some ways, the writing reminds me of the grander “ornamented chorale” style preludes, and that sense of scale is a bit lost on lighter sounds. I’m also not entirely confident that my understanding of “oh how vain, oh how fleeting” would necessarily match an 18th-century Lutheran’s. Is the organ supposed to sound like the impermanent affairs of this world, or like the solidity and steadfastness of the Divine? I’ll probably go back and forth on registrations until the performance; let me know what you think of the sound I pick.

Don’t tell the other children, but the C-major Trio Sonata might be my favorite. Not my favorite trio sonata—not even just my favorite Bach organ piece, but possibly my favorite piece by Bach and my favorite piece in the whole organ repertoire. (I hope this doesn’t dissuade anybody from coming to future entries in the series! It’s not entirely downhill from here.)

What’s to love about this piece? Like last week’s G-major sonata, it’s hyper-“modern,” which is to say Vivaldian. Take the first movement, where that influence shows up in a few different ways. First, you have the frisky and distinctive opening hook, which wriggles all over the keyboard in one measure and then bounces up and down in one spot for the next. This rhythmic energy is infectious: practically the only time the movement’s running sixteenth notes stop is for the “bouncing” figure, which comes back often enough to give nice breaks, but without stopping the piece’s drive. And when the two are combined, you get delightful effects from the pedal “bouncing” to the beat under the “running” parts in the hands. A Finnish person might say this movement “grooves like a moose.”

I don’t think that’s the only thing that makes this movement tick, though. Another aspect of the Vivaldian influence is the seemingly endless use of sequences, where a bit of music is repeated in a fixed pattern of keys. When used well, they’re incredibly satisfying, matching predictability to variability in delightful ways; but when over- or misused, sequences are just plain predictable. (Again, this is one of the most common knocks against Vivaldi—fairly or unfairly.)

So for example, the most common pattern would be to take a passage down the circle of fifths: play it first on D, then G, then C, etc. You’ve heard something like this in practically every piece I’ve played in this series; here’s an example from the last movement of this sonata:

The repeating pattern is probably easiest to see in the pedals (bottom line): even if you can’t read this kind of music notation, you can see the similar shapes going up and down the staff by a fixed distance. And the effect is somewhere between running on a treadmill and slowly letting the air out of a balloon: it’s a very effective way to manage the release of musical tension, keeping us listeners engaged and locked into the groove while the music bides its time for the next big thing.

But compare that to a representative page from the first movement:

Again, you don’t need to be able to read this kind of notation to notice what the pedal part is doing. On the first system, it repeatedly takes the same pattern up by steps. After waiting patiently on the next line (more about that to come), it takes a different pattern up the scale, and then (going onto the fourth system) yet another one. For practically a whole page, Bach has had the bassline give at least the illusion of continuously rising, constantly upping the ante and raising the energy level. And the whole movement plays off of combining the opening figure, with its almost childlike sunniness, and this incessant upward drive in the bass. The pedals: “I Want to Take You Higher.”

I’m still not quite done with the first movement: time to talk about the “B” section, and also those spots where the pedal stands still. I think this music would be pretty fatiguing, or even cloying, if it just stuck to “running” and “bouncy” with these rising sequences. So they’re regularly interrupted by sudden intrusions from minor keys—“purple patches” that last just enough to make us welcome the breezy opening music back with open arms. Eventually, we even get a minor-key version of the opening music, a slightly longer “dark shadow” intense enough to make us grateful when Bach brings back the first fifty measures to close the piece. (How does he make his way back to the opening? Another rising sequence, of course.)

The second movement has something of the same function for the piece as a whole: it lives in the same somber harmonic world as the St. Matthew Passion or the “Agnus Dei” from the B-minor Mass, making the outer movements seem even more cheerful by comparison. It’s also bewitchingly beautiful by itself; it seems that Bach picked this movement out of his earlier organ works and built a sonata around it. And the third movement that he either chose or wrote to round things off complements the other two perfectly. As athletic and spry as anything in the Brandenburg Concertos, this movement couples some of the darker harmonies of the previous two with an overflow of sheer exuberance. It’s just too much fun to let your feet jaunt across their whole range. Sometimes they run; sometimes they jump. But they (and you, the listeners) won’t get a break until the very end.

How about something a bit calmer after all that? This Aria is the most direct trace of French influence in Bach’s organ works, although we certainly have lots of other evidence for it.1 The funny thing is that this is not a transcription of Couperin’s most “French” music. Couperin is credited with bringing the Italian trio sonata to France (and writing an Apothéose of Corelli), and this movement is extracted from a set of sonatas titled, well, Les Nations. Still, just as Bach can’t help but lace his Italian-style music with counterpoint, Couperin’s Italian music has a strong French accent. (And Couperin is imitating an older generation of composers than Bach’s Italians.) Hopefully placing this Sonata and Aria side to side helps to point up how different these international versions of musical Italy could be.

I was originally going to label BWV 545b something like “Prelude, Adagio, Trio, and Fugue,” but given everything I’ve said about the title “Prelude”—and the fact that practically nobody knows this piece—I thought I should stick to my guns. Just be warned that there are something like five sections in this piece, exactly like the Buxtehude-style organ Præludium.

Well, maybe not exactly like that. Instead of having two fugues at the end, this piece inserts a slow movement and a trio between two loud free sections (and before the closing fugue). And you might recognize the trio, if you happen to know Bach’s sonatas for viola da gamba: this is a version of the last movement from BWV 1029.

How is it possible that “practically nobody knows this piece”? (I mean the organ piece; that wasn’t intended as a dig at gamba players.) I should clarify that I meant this version of this piece. The C-major prelude BWV 545 is reasonably well-known, whereas this B-flat major version has languished in obscurity. And truth be told, it’s unlikely that it’s by Bach. The only surviving manuscript is pretty late (a bad sign) and English (even worse); the “new” sections” are desperately clunky; and the arrangement of BWV 1029 is awkward in ways that “authentic Bach” never are.

Why play this version then? For starters, it’s very nice to be able to filch some of the gamba sonatas, especially this movement, which alternates between rhythmically complex show-off music and nice lyrical interludes. And I do like playing more music in different keys. It’s nice to just be able to say “B-flat Major Prelude” instead of “C maj—…well, let me tell you the BWV number….”

The other reason is “historical.” Early on, or maybe even originally, BWV 545 included a different trio movement between the prelude and the fugue. And the trio movement was none other than (what became) the slow movement from the fifth Trio Sonata. I love the effect of having a trio between the prelude and the fugue, but while it’s tempting to just play it again, it does feel a little bit repetitive to include the same five-minute movement twice on the series. Luckily, this version gives us a way out, by handing us another trio to slot into the same position. In any case, I put the Trio Sonata and this Prelude on the same program to let you decide: which trio movement would you prefer as an interlude? Bach’s choice or the anonymous 18th-century Englishman I went with? Without trying to sound snarky or contrarian, I personally wonder if the English weren’t onto something…

The Reneker Organ (Part 1)

Seven weeks into the series and I still haven’t told you anything about the organ. It’s high time to fix that! I’ll focus less on the specific history of the instrument and its builder (you can read about that here) and more on its sound and action. I apologize to organists reading this: it will probably be very basic for you, and you may just want to skip this entry. I’ll put a summary of the more technical details in a footnote here.2

The Reneker organ was built in 1983, a generation or two into the “Organ reform movement” that gave us Neo-Baroque style instruments. That means that, in many ways, it tries to sound and feel like “Bach’s organs,” but its version of that ideal is somewhat abstracted from the specific organs Bach played and heard. While more recent organ builders will often copy specific stops or even whole organ dispositions from historic instruments,3 this one gives a generalized version of what Karl Wilhelm thought “Bach organs” ought to sound like. (And conversely, as compared to earlier Neo-Baroque instruments, an organ like this is a lot less likely to sound thin, shrill, or squeaky.)

What was being reformed? Well, something like the instrument in Rockefeller Chapel! A beautiful orchestral instrument like that is perfect for layering sounds, creating rich tapestries with lots of solo colors. The Rockefeller instrument is great for enveloping or overwhelming you; it’s smooth as butter, rich as a cream sauce, and makes practically anything you play sound luscious.

That all sounds great—unless you’re a modernist composer or performer who’s prioritizing things like “precision” and “clarity.” Those are attainable on instruments like the Skinner in Rockefeller, but you have to work for them. On the other hand, the Reneker in Bond is almost too precise. It does exactly what you play—and thus gives you nowhere to hide.

How can the instruments be so different? Two big factors are pipe voicing and keyboard action. (The sizes of the spaces and organs also play a role.)

Voicing is probably the more subtle one. You’ll notice that there’s a distinct attack at the beginning of each note on the Reneker organ. It’s possible to get less “chiff” by playing less aggressively, and to cover it up by playing more legato, but no matter what, each note has a “consonant” at the beginning. Meanwhile, the Rockefeller instrument has notches cut into the mouths of each pipe, lowering turbulence when the airstream begins to pass through it: much less chiff. The best way to get a strong attack on most of that instrument’s stops is to simply play louder, and a little crisper—sort of like trying to add a glottal stop on a vowel-initial word.

Part of the reason it’s possible to control the degree of chiff on the Reneker organ is the action. This instrument, except for the music stand light and the electric blower powering the windchest, is entirely mechanical. When you press a note, a series of wooden and leather “trackers” (levers, pulleys, etc.) is taking your physical touch and using it to open the pallets that let wind into the pipes. Compare that to an electro-pneumatic instrument like the one in Rockefeller: you press the key, two electrical contacts connect and complete a circuit, which triggers a motor to open the pallet for you. It’s a completely binary process, and you have substantially less control. There’s no way to gently pry the pallet open on an electric-action organ—but you wouldn’t need to, since the pipes at Rockefeller won’t give you too much chiff even if you slam the air into them all at once.

One of the side-effects of a mechanical action is that the heft required to play the keys changes dramatically depending on how many stops are drawn. Coupling two manuals together is literally twice as heavy (or even more), since you end up literally playing the keys from the coupled-in manual at the same time. Luckily, unlike some surviving historical instruments (in their present condition), the Reneker will never give you a full forearm workout trying to play loud music.

There’s also a matter of the actual pipe construction and selection of sounds. Let me defer discussion of that to a later week; I’ve made enough recordings to be able to give you a virtual audio tour of this instrument, and it makes more sense to talk about the sounds there. I’ll just say that, on the whole, Baroque and Neo-Baroque builders used narrower-scale pipes (giving a slimmer sound), and that some construction techniques (harmonic flutes and reeds) weren’t invented until the nineteenth century anyway.

The last two major differences that you might notice in the sound: tuning and wind. Unlike a piano or the Rockefeller organ, the instrument is tuned in Herbert Anton Kellner’s temperament, in which keys close to C major sound very nice and those close to G♭/F♯ sound pretty out of tune.4 Like most “Bach temperaments,” this probably isn’t exactly how Bach or anybody else tuned their organs, but it has all the properties you could hope for: “core” keys sound especially good, “distant” keys sound strange and harsh, but everything is playable. Remember that Bach has pieces like the C-minor Prelude BWV 549, which uses both C♭ and B♮, C♯ and D♭. While we’d like for all of those notes to sound at least OK, it’s good for C♭ to sound more unusual than B♮. This instrument does that well.

A similar idea applies for the wind supply. With modern electric blowers, of course, you can feed as much wind pressure into the organ as the pipes will take. But that’s not what any Baroque organist had available: instead, people had to physically pump the bellows by hand or foot. (Now there’s a reason to have 20 children.) The result was a certain amount of flexibility and just lower wind pressure in general. That doesn’t mean that the wind should be scanty. Reportedly, when testing out a new instrument, Bach’s first step was to pull out as many stops as makes sense and play at maximum volume: the most important thing to check was the organ’s “lungs.”5 Still, that doesn’t mean he expected the wind pressure to remain completely uniform. As with tuning, it’s good to be able to hear the instrument work a bit when the writing is is extraordinarily thick—but it shouldn’t give out entirely.

What I’m Listening To

FARATUBEN – Changement

I missed FARATUBEN’s first album, so this was my first exposure to the group. The name gives their concept away—farafin+toubabou, “black+white” for a band of musicians from Mali and Denmark. The musical upshot is something like a club-ified version of Bobo music, starring Malian musicians on guitar and balafon, with the Danes on drums, bass, and synths. And that combination actually makes a lot of sense if you think about it (or listen): in context, you could almost (almost!) confuse the balafon for some electric piano or synth sounds, although the tuning is a dead giveaway.

My biggest worry when seeing FARATUBEN’s concept was that either one “side” of the equation would overwhelm the other, or that the two would sort of just take turns. And the first half or so of the album does suffer a little bit from the latter: it more or less alternates between balafon-dominated tracks and synth-heavy ones. But things smooth out pretty quickly. By the time we get to “Immigration” (a real highlight for me), all of the elements genuinely start to play off of each other. (The song’s title also hints at the band’s broader lyrical message. Unfortunately, the lyrics are lost on me and seemingly unsearchable online.)

In case it hasn’t been obvious, I’m predisposed to like this general kind of music—campursari forever!—but I also think this is an awfully likeable album. The contrast and blending between the different musical spheres (not just balafon vs. synth, but also European vs. Malian ways of using electric guitars) keeps things fresh and interesting. It’s nothing too hardcore or intense, but the album also never ever drags. It’s a great time!

Peter Leech and Costanzi Consort – Casali: Sacred Music from 18th Century Rome

More obscure century 18th-century Italian music.6 Unlike last week, I won’t try to convince you that this is necessarily music you’ll love listening to by itself (or that the performances are my favorite ever). But it sure is interesting! Despite being born at the same time as Gluck and C.P.E. Bach, Casali can make J.S. Bach look downright hip: he must have been one of the last composers to write this kind of a cappella sacred music before the Cecilian Movement revived the style in the 19th century. At the same time, Casali writes in a highly simplified style that reminds me a whole lot of Haydn and Mozart masses. I knew the story about Mozart transcribing the Allegri Miserere from memory; I just didn’t realize that there was Allegri-descended music still being written in Rome at the time.

Jesse Rodin and Cut Circle – Josquin I. Motets & chansons

By contrast, for “early music people,” this recording is something like a greatest hits album. “Ave Maria,” check; “Miserere,” check. “Stabat Mater,” check. Most of the chansons you would expect to see make an appearance too—given its absence, it may be that Rodin will just not include “Mille Regretz” in this batch of recordings at all.

What about the performances? Cut Circle, along with a couple of other ensembles (Graindelavoix is the most extreme) are taking a fairly radical approach to singing Renaissance polyphony. Part of the novelty is just a willingness to take zippier tempos and give more emphatic articulations, both of which I (of course) find very easy to appreciate, and which are extremely refreshing if you’ve mostly heard this music from the sometimes molasses-like Tallis Scholars.

But more noticeable is their approach to vocal timbre. Not only are Cut Circle much freer with vibrato than “English choir” ensembles like the Tallis Scholars—they’re also seriously willing to experiment with completely different approaches to vocal technique. Especially in chansons, they sing in much more stylized registers, including open-throated sounds verging on shape-note style (“Faulte d’argent”).7 This allows for much more extreme text-painting than most groups can get: cries are actually cried out, shouts are shouted, whispers are whispers. Sliding between pitches is fine.

All of this is reined in somewhat in the motet recordings.8 Most interesting, then, is the selection of well-known pieces that combine sacred and secular elements: the “Stabat Mater” incorporates “Comme femme desconfortée” and “Nimphes, nappés” includes “Circumdederunt me.” If Cut Circle are going for a contrast between the voices, I find it hard to hear; but they do make major timbre shifts between sections in a way that makes the structure pop.

I’m still getting used to this singing style, and maybe it’ll never be my favorite, but these really are interpretations worth listening to. Rodin knows Josquin’s music about as well as anybody else since the 16th century, and these recordings reflect that deep understanding of what makes his style work. And if you don’t know these pieces, be warned: you’ll probably find other recordings disappointingly flat after hearing this one.

Jungkook– “Standing Next to You”

Look, I didn’t see it coming either. It’s pretty commonly agreed (including among a large chunk of ARMYs) that BTS’s music has been going steadily downhill since…some point in time that depends on when you first encountered them. Let’s say 2017 (although plenty of people will say they peaked in 2016, 2015, or 2014…or that the occasional good song since 2017 invalidates the trend). Certainly, the constant whirlwind of touring and promotion since then wasn’t good for their music, and their recent solo releases have just sounded creatively exhausted to me.

Did I mention that I really didn’t like any of the pre-album singles Jungkook put out?

But then there’s this song, and it’s not even the only good one on the album. “Too Sad to Dance” is catchy in an Ed Sheeran kind of way, even if there’s a bit too much dead time for me. “Please Don’t Change” does a pretty decent version of the whole “tropical” thing, as do parts of “Closer to You.” I don’t even hate the ballads.

Even compared to these, “Standing Next to You” is something else entirely. It does a lot of the same stuff that 2022 Harry Styles was trying, only significantly better. The beat is great: lushly space-filling and constantly popping with great licks, the instrumentals reliably jump in whenever there’s a long break in the tune. (But they manage not to sound hyperactive or oppressive.) And once the prechorus gets started, the tune really is loaded with hooks. The Michael Jackson callbacks of “All night long…” The falsetto in “in the fire next to you.” The rhythmic complexity of “Deeper than the rain / deeper than the pain…” (I did not say that the lyrics are any good). And the cherry on top at “Take-take-take-take-take-take off.” Unlike so many BTS releases in recent years, this song is memorable.

Why? What took them so long?

Well, unlike the other solo projects, this one is really trying to be pop, and Jungkook isn’t trying to be an “artist” in the same way that Suga and J-Hope are; he doesn’t have a single songwriting credit on the album. V also didn’t write any of the songs on his album either, but his version of lowkey R&B isn’t exactly the best way to grab a ton of people’s attention. (Even if somewhat anaesthetized music is a big part of the US charts nowadays.) This is clearly music by somebody actively trying to grow his fanbase.

It’s also all in English. As if that’s a coincidence.

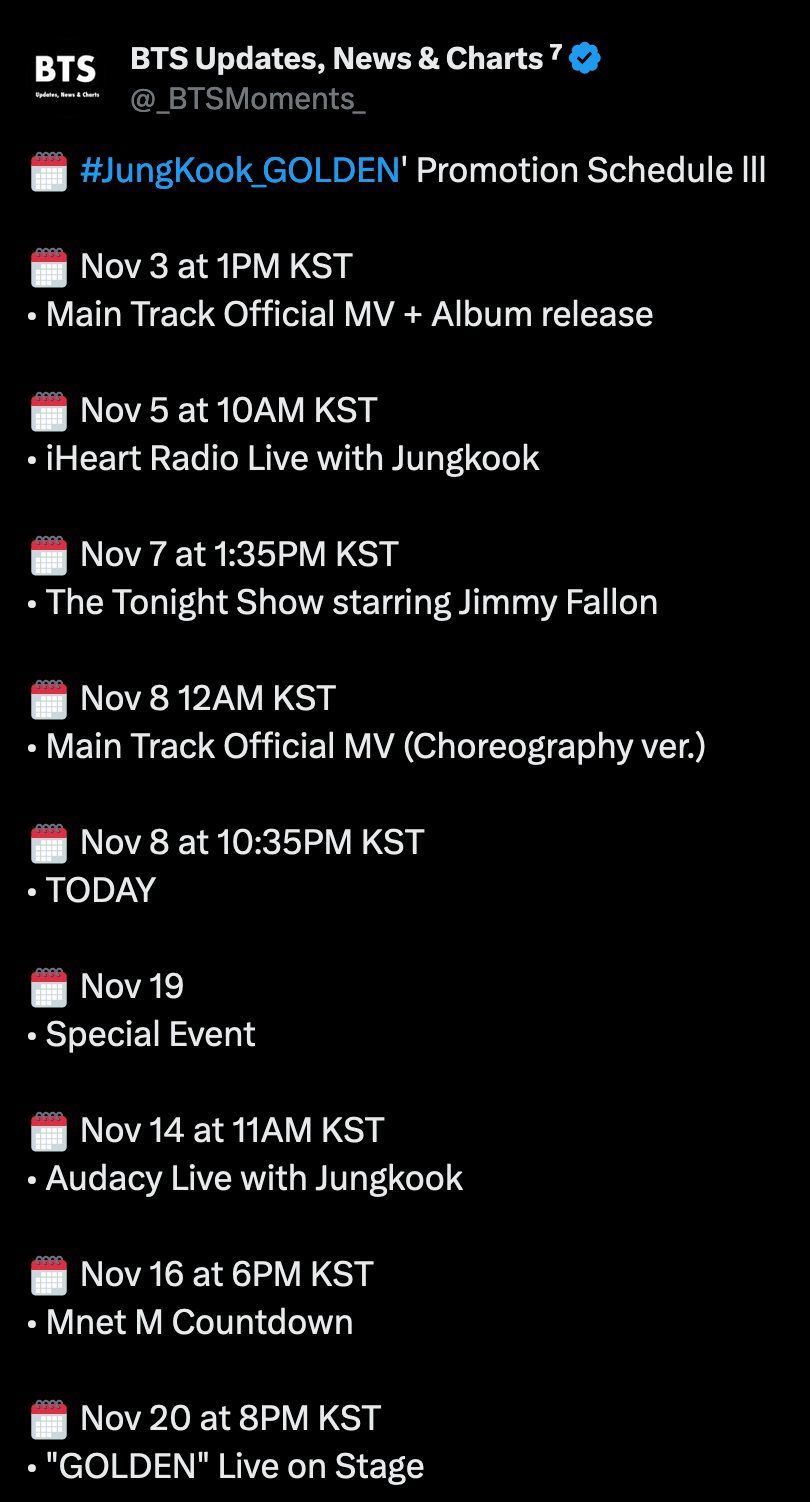

Yes, you read that correctly: the first promotional events for this album were on iHeart radio and Jimmy Fallon. “Coincidentally” (but not for the first time), Bang Si-Hyuk, the label chairman who made BTS, has recently advocated for taking the “K” out of “K-pop.”

It’s not just Jungkook, or BTS, or Bang Si-Hyuk. SM has announced that æspa’s first full-length album will be in English. (G)I-dle’s first English EP fits in perfectly well with a discography that’s over 50% in English. And in general girl groups have increased their usage of English by almost 20 percentage points since 2018.9

There’s nothing wrong with this in the abstract, although I wish (G)I-dle’s Soyeon would let her English-fluent members write or at least edit those lyrics.10 But more than that, I wish the songs on their English album were better! The biggest problem with K-pop in English has never been English itself: it’s been that the songs sucked.

Why?

It’s not as simple as noting that English-language K-pop songs are imitating recent American chart hits. K-pop is always doing that. But, due to the much more intense competition for “catchy” pop in Korea, the music is usually much more concentrated: more hooks, more stuff going on. And also more different stuff; it’s harder to stand out in such a market, so you’re more likely to take a musical risk. Take the best song actually written by Bang Si-Hyuk:

There are a ton of synth layers, but this isn’t spectacularly overproduced, and it’s not the most “maximal” production of all time. Instead the song relies on three things: a catchy rhythmic interplay with the synths, great tunes for both verses and chorus, and the insanity that happens after the break at 2:43. The rapping is whatever, but the sliced-up and flipped version of the beat that follows it is fantastic and different and exactly the kind of risk that you’re unlikely to see American Top 40 producers take (or even bother to think up).

On the other hand, when K-pop producers imitate the dregs of American pop music, you get a general sense of dullness, of songs that feel weirdly empty or don’t go anywhere. Music that’s been sanded down to nothingness. Part of the reason for me to be so pleasantly surprised by Jungkook is that—at least for half an album—he could resist this trend. I hope other artists take notice.

All of this is just me speaking for myself. When it comes to the “English takeover,” this might not be the main fear that Koreans or international K-pop fans have. Aside from non-Koreans wanting to feel “different” or not wanting to be able to understand the lyrics (there’s a reason I didn’t give a captioned video for the T-ARA song!), there’s perpetual angst about what it means for a “Korean” cultural product to “internationalize.” Never mind that “K-culture” is hardly associated with some deep cultural essence of “Koreanness,” given that it’s mostly a localized version of American influences.

Or maybe (for some people) it’s more strongly tied up in national identity than I thought:

Although the actual lyrics of this song have nothing to do with all of the signifiers of “TRADITIONAL KOREA” in the music video, the hanbok isn’t at all out of place in the song’s concept: Heejin’s album is called K, after all. Clearly, at least some K-pop artists/labels would like to insist on the connection between K-pop and Korea, beyond just who makes the music.

On the other hand, Heejin’s promotion of “Korean culture” isn’t limited to traditional clothes and temples:

HeeJin: I want to emphasize the Korean culture for this album at a time when K-Pop is becoming more global and becoming a genre on its own. I want to show the audience some freshness with this album while being able to experience Korean culture. Something I really love about Korea is the convenient services. For example, in the middle of the night, you can get so many foods through delivery services. In my case, I love eating chicken feet or tteokbokki in the middle of the night. So, whenever I want to eat something I can get it delivered — that's one of the things I like about Korea.

If only Bang Si-Hyuk had thought of that. Instead of trying to take the “K” out of K-pop, he should be helping the rest of the world get tteokbokki delivered in the middle of the night. I look forward to the BTS song about that.

Also liked…

Nicholas Collon and Finnish Radio Symphony with Christian Tetzlaff – Lutosławski: Concerto for Orchestra, Partita (fantastic performances that I have nothing to say about)

Marcos Coll – Nómade

Hotline TNT – Cartwheel

Ziya Tabassian – Remembrances

Bruce Liu – WAVES (mainly for the Alkan)

What I’m Reading

Similarly to last week and Christoph Wolff’s new book, it might seem a little funny (if you know my research interests) that I only just got through Joseph Lam’s new book on Kunqu 昆曲. In my defense, I did check immediately when it came out to see if it had anything to say about the theoretical literature I study (quhua 曲話), and I put it on the backburner after confirming that it didn’t.

That’s not meant to be a knock on the book, which does (as far as I can tell) a good job of covering the basics of kunqu singing, stagecraft, gesture, and production. As his subtitle indicates, the major focus is on what kunqu means today: how it’s been enlisted in the service of historical and cultural narratives that both the PRC as a whole and individual local governments would like to put forward. Lam does a great job of dissecting some of the incentives that cause kunqu to be promoted the way it does, especially when it comes to the motivation of particular institutions.

I have to say that I think the book sometimes falls into the same trap. (I don’t want to attribute this to Lam himself, since for all I know it’s related to the press or the editor.) There’s an awful lot of language in this book about how well kunqu matches with “traditional Chinese” structures of feeling, deep-seated philosophical beliefs, etc. And there are some pretty strange passages, for instance comparing kunqu’s role in promoting “historical consciousness” to tours of the Three Gorges Dam and the mammoth Siku quanshu book collection project. For a book that’s so good at exposing the agendas of others, I sometimes wondered about its own project.

Still, this is now by far the best English-language introduction to kunqu available, and it does its main job well. If you don’t know much about Chinese opera, it should still be pretty accessible, and you’ll have a pretty decent overview of one of its major forms by the end of the book.

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

e.g. his copies of Nicolas de Grigny’s Livre d’orgue, or his inclusion of Couperin in a Notebook for Wilhelm Friedemann.

The organ is a 2-manual, 33-rank Neo-Baroque instrument with mechanical action and no combination action. It’s tuned in Kellner and has flexible wind. Flat straight pedalboard (highest note F4) and keyboards going up to F6. Here it is on the OHS database: https://pipeorgandatabase.org/organ/50916.

And the really committed ones now try to even restrict themselves to tools and manufacturing techniques that would have been available in the early 18th century.

I’ve always wondered if the massive chords at the beginning of BWV 549 hint at this practice. Combined with the unusual chromaticism, it certainly makes for a good “organ test drive” piece.

Be glad I left “Mario Bianchelli” (who?) on the cutting room floor this week.

Singing like this inevitably reminds me of the phrase from Isidore of Seville that Richard Taruskin used to praise Gothic Voices’ singing: “High, sweet, and loud.”

I first really noticed Cut Circle’s singing style on their Ockeghem Chansons disk—but maybe that’s because almost all of the previous recordings were of masses, where they’re also much more restrained.

Since the promotion of boy groups in Korea depends much more on cultivating intense fan attachments to the stars, girl groups tend to be forward indicators for trends. (And, on the whole, to have catchier and better music.)