Week 23: 8 April 2024 – “Jesu, meine Freude”: Easter 2

Plus: cadenzas and ornaments, j-hope takes to the streets, AKB48 scholarship, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

There is a lot of music being made right now under the label “shoegaze”: search Spotify for “Japanese shoegaze” alone and you’ll be confronted with multiple distinct playlists stretching into the hundreds of hours. And, like most musical booms, this one is fueled by a relatively low barrier to entry. Nobody will complain if your shoegaze sounds the same as everybody else’s—they’re just there for the midtempo wall of distortion and reverb, the depressed singing and lyrics. It’s not a problem if you don’t stand out. And conversely it’s very hard to stand out if you actually want to.

Maybe it takes a different perspective to bring something new to a genre like shoegaze. Ojibwe musician Daniel Monkman definitely does that: they’ve coined the (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) label “moccasin gaze” for songs like “Was & and Always Will Be” that refresh the genre by incorporating Ojibwe drumming, flutes, chants, and other musical elements. It’s a great idea, and the same sense of musical freshness enlivens more by-the-book shoegaze/dreampop songs like “Vibrant Colours” from the same album. And the same goes for less obviously “moccasin gaze” musical projects, like the hip-hop-inflected Big Pharma, or the more traditionally shoegaze Bekka Ma’iingan. Still, the thematic concerns are the same: Bekka Ma’iingan’s lead single is “A Language Disappears,” and it features songs like “Niizh Manidoowig (2 spirit).” Luckily, Monkman’s work with Zoon has deservedly gotten some degree of recognition: you can read interviews with them here, here, and here.

Week 23: 8 April 2024 – “Jesu, meine Freude”: Easter 2

Please save applause for the end of each set

Adagio in D minor, BWV 1001/i (arr. Reed)

Fugue in D minor, BWV 539/ii

Fantasia super Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 713

Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 610

Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 1105

Concerto in C, BWV 594 (after Vivaldi’s Op.7 No.11 “Grosso Mogul,” RV 208)

i. [Allegro]

ii. Recitativo: Adagio

iii. Allegro - Cadenza - Allegro

Now that Lent’s over (and the glut of Easter chorales has passed through our system), it’s time to return to “chamber” music. This week features a double helping—not only a Vivaldi concerto, but also an arrangement from Bach’s first Violin Sonata.

Or, well, two arrangements: you might know the D-minor Fugue BWV 539/ii as the “Fiddle Fugue,” since it’s derived from the second movement of that sonata. We don’t know who did the arrangement, but it’s not entirely clear that it should be attributed to Bach, since no autograph manuscript survives. That’s not an unusual situation for Bach, but doubts really begin to spring up from the style of the arrangement. There’s lots of evidence on one side: all those Vivaldi concerto transcriptions show how clever Bach could be in bringing violin writing over to the keyboard. By contrast, this Fugue is somewhat awkwardly arranged for the hands and feet.

So, I’ll happily admit to having taken some liberties with the arrangement—it’s easier to justify doctoring if you think it wasn’t done by Bach. The most drastic change would be in this passage of eighth notes, which, when played literally, completely kills the momentum:

Baroque violinists have, I think, had the right idea in how they play this part of the violin fugue. Listen to what Isabelle Faust does starting at around 1:30 in her recording—extrapolating from similar passages in the D-minor chaconne, she turns these triple stops into arpeggios, which greatly enlivens the rhythm. And Faust is hardly alone: to cherrypick two more recordings, you can hear Jennifer Koh do the same (around 1:49), or Midori Seiler do her version (1:38). I’m more than happy to learn from their example and spice up this fugue.

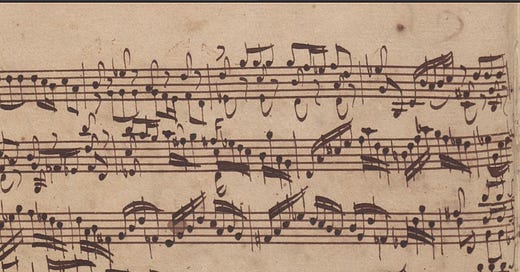

Lest I sound like I’m just copying Baroque violinists (which wouldn’t be the worst outcome!), I’ll say that I’m frankly confused by the “standard” interpretation of the Adagio that comes before this fugue in the original sonata. Basically every violinist, including the three above, plays that Adagio like it’s from a quiet middle movement of a funeral cantata. But, to my organist brain, the piece looks and sounds like nothing so much as the G-minor Fantasy BWV 542/i—just compare them visually, even:

versus

And no organist would play that piece with the thin, slightly washed-out sound that violinists like to adopt for the Adagio. The organ sound you would want is loud and in your face.

In any case, the upshot is that the Adagio arranges splendidly for the organ, as a kind of G-minor Fantasy-style prelude to the “Fiddle Fugue.” Even the pedal part takes practically no thought to think up.

What about BWV 539/i? Well, you know I can be pretty lenient about including music that’s “questionably” by Bach. But not when it’s this bad. (I can make other excuses—the fugue survives in a lot of manuscripts without the BWV 539 prelude—but for me the decision to ditch the piece mostly boils down to its utter yawnworthiness.) And especially not when there’s a ready-made Bachian alternative that almost arranges itself. (To say nothing of the opportunity to maybe prove a point to violinists about how to play the piece.)

So, while neither the Adagio nor the Fugue may have been arranged by Bach, at least in this version we know for sure who wrote both original pieces. Besides, playing solo violin and cello music on keyboard instruments seems to have been a very Bachian practice. Really, maybe the most “authentic” thing to do might have been to add the Adagios and Fugues from the other two violin sonatas to the series as well.

“Jesu meine Freude” is slotted in for Epiphany in the Orgelbüchlein, and indeed Bach mostly used it for Christmas and Epiphany cantatas. But it’s a versatile tune, and he did also use it for a few Eastertide pieces. Christmas and Epiphany are crowded. So that’s why we’re getting this music now.

As all that would indicate, this was a pretty important hymn for Bach. Four cantatas (extant ones at any rate), three chorale preludes, and an extraordinary, justifiably famous funeral motet:

You may have even heard the theory that the English Suites were arranged in the sequence of keys A-A-G-F-E-D to fit this tune. Seems unlikely, but it’s a fun idea. And one that shows just how prominent “Jesu meine Freude” is in the imaginations of Bach-a-holics.

As you might hope, Bach’s chorale preludes on this tune all show an unusual degree of care, and some neat ideas. Most original of all is BWV 713, an early piece that starts out as a fugue with the chorale in long notes freely floating around as a fourth voice. That’s already pretty cool, but the second half switches things up even further, changing from 4/4 to ⅜, marked dolce. (My closest comp is the B-minor Fantasy, with its ¾ imitatio.) Having started in the style of a German keyboard fugue, the music ends up sounding like a French trio; and the tune is now a lot less obvious to pick out. And then there’s a “plain” figured-bass setting of the chorale to round things off.

The Orgelbüchlein “Jesu meine Freude” is a lot less formally idiosyncratic, but shows an equal amount of thoughtfulness. Honestly, the format of this chorale is the opposite of idiosyncratic: if you’ve been following along, you would probably guess that, as an Orgelbüchlein chorale, this one is likely to be “tune on top, imitative figuration below.” And you would be correct. But the figuration isn’t usually quite this expressive, and the harmonies aren’t usually quite this juicy.

And then there’s the Neumeister “Jesu meine Freude,” which—again, as you’ve hopefully learned to expect from Neumeister chorales—throws the idea of consistent form entirely out the window:

That said, the design of this one is pretty clear-cut and thus a bit more dramatically effective. For the first two lines of the chorale, the tune is played in the soprano, then the tenor, then the bass, with a shifting cast of figuration types around it. After that it stays in the soprano, but the texture continues to change every couple measures: start-and-stop; running sixteenths; chunky chords. Somehow, it doesn’t manage to sound incoherent or random. The tune holds everything together. Leave it to “Jesu meine Freude” to inspire the best out of the young Bach.

This is another program that looks awfully short, and I’m here again to tell you that the final piece is long. Not quite “Sei gegrüsset” length, but something on the order of 17 minutes. Not only is that long for a Bach organ piece: it’s extraordinarily long for a Vivaldi concerto. A typical recording of L’estro armonico will typically run under 100 minutes, and that’s for twelve concerti. In other words, the outer movements of “Grosso Mogul” are approaching the length of a whole L’estro armonico concerto all by themselves.

Before you ask, I don’t really get the “Grosso Mogul” nickname either. Supposedly the concerto was once associated with one of the many Il gran Mogol operas. But why is the Mughal in question named “Tisifaro”? Impossible to say; I somehow doubt that’s a corruption of “Jahangir” or “Aurangzeb.” (And I really don’t know why every Baroque opera has some dude named “Argippo” in it.)

Anyway, the music. This concerto is the most Vivaldi Vivaldi to ever Vivaldi. If you asked ChatGPT (or the musical equivalent, ChatZPT) to make 7 minutes of fake Vivaldi for you, it would probably sound exactly like the first movement of this piece, albeit not nearly as good. Just look at it:

Repeated notes, check. Octave jumps, check. Scales, check. Cryogenically-frozen harmonies, check. Put the opening of the Gloria in a blender with RV 522 and strain the results to get rid of lumps or fiber. Pure, unadulterated Vivaldi.

So it’s kind of dumb music, but also really really fun. Or at least it’s dumb-sounding; plotting the harmonies out for such a satisfying and thrilling effect is no mean feat, one that takes very careful calibration. Consider the opening again. After gradually outlining C, first as a note, then as a scale, and then as a chord (see above), Vivaldi then points us to its “nearest-neighbor” keys:

One flat ♭ and then one sharp ♯: in these few measures, Vivaldi begins to open the harmonic universe up for us. And the moment he’s done so, he also gives us a glimpse of minor keys:

So, even if all of the figuration sounds utterly mechanical—and it is—this is actually seriously methodical music.

Anyway, we were talking about dumb fun. Even more than the original, Bach really leans into this by writing extremely long solo passages, often outlining nothing more than a single chord:

And this is showy stuff—those repeated notes go just about as fast as the organ can play them. To say nothing of the fireworks that come in later:

In Bach’s version (and some copies of the Vivaldi), this passage even leads into a long cadenza to close the movement. Hold that thought.

The slow movement is also exceptionally florid, to the extent that I don’t feel like I have much to add to the music. (Contrast that with what I do, for instance, to the slow movement of the A-minor concerto.) If this is what recitatives could sound like, our Baroque opera performances need a lot more ornaments. (Somehow I think that this movement might be a little bit stylized—or else no recitative listener could possibly have heard any of the words.) It’s a striking reminder that Baroque musicians thought slow movements were just as important for showcasing virtuosity as their fast counterparts.

Back to dumb fun for the third movement, with a theme that really does just tumble down a C-major triad, and then climb right back up:

Things don’t get any less meatheaded from then out. And the most spectacular moment comes about as a kind of climax of violin-bro shredding: a 100-bar cadenza that interrupts a movement lasting less than 300 measures altogether. And the cadenza is as rapid and empty (*Spinal Tap voice*: “Rock and Roll!”) as you might hope:

Eventually, all that momentum takes the cadenza totally off the rails. That’s what’ll happen when you get two whole pages of the same arpeggios, traveling down the circle of fifths in sequences:

As you can see by the bottom of the page, those sequences take the music to some crazy places. To state the obvious, double flats are not common in Baroque music. Even an utterly simplistic process like this, working with the bare minimum of musical materials, can produce fascinating and innovative results. Vivaldi’s dumb fun disguises a great deal of musical depth. This is our last concert arrangement; enjoy it while you can.

What did they think it was OK to add?

By now you’re probably wondering what the original violin part for that cadenza looked like. Luckily, a holograph manuscript of the “Grosso Mogul” concerto has been digitized! Let’s see what it says:

Oh.

To be clear, Bach didn’t make his cadenzas up out of whole cloth. There are multiple manuscript copies with elaborate cadenzas, and Bach’s derive largely from such sources. They might even be from Vivaldi; funny enough, the published version (Op.7 No.11), which lacks the additions, is less likely to be authentic than these. (Op.7 is not the most reliable collection overall: Dutch publishers could be pretty unscrupulous.)

Probably under Vivaldian influence—as in, inspired by this exact piece—Bach later wrote gigantic cadenzas into two of his harpsichord concertos. Brandenburg 5’s first movement includes a solo senza stromenti that takes up over 60 of its 227 measures; the D-minor concerto BWV 1052 doesn’t go quite that long, but includes several dozen-bar-long passages that are either solo or only minimally accompanied by the orchestra. And there are fermatas in the latter that presumably indicate places to add further solos.

These pieces all stand out today, and it’s possible they stood out in their own time. Most Vivaldi concertos don’t have specific instructions for a cadenza, and most Bach concertos aren’t as extravagant as Brandenburg 5.

Still, it’s entirely likely that the norm was closer to these pieces than we think. A number of Baroque treatises include dicta along the lines of “It is not tasteful to play a cadenza that is longer than the piece itself.” (A couple such are sampled in The Pursuit of Musick.) You could say that that’s hyperbole. But even if they only felt that long—is that even true for the “Grosso Mogul” cadenzas?—it must have been fairly commonplace for musicians to add a lot of music. In performance the L’estro armonico concertos might not have been so different in length from “Grosso Mogul.”

The same goes for all those ornaments in the slow movement. Yes, as written, this is an exceptionally well-decorated solo line. But there is all sorts of evidence from Baroque sources for playing “plain” solo lines with this level of ornamentation. To give a few well-known examples, you have Corelli’s Op.5 (the “original” violin part is the middle line; the top line contains ornaments supposedly added by Corelli himself):

And the even more extreme sets of ornaments attributed to Tartini by Jean-Baptiste Cartier (the top two lines are the original piece; the rest are all possible ways of executing it):

For something a little closer to Bach’s time, you could see the ornamented versions of Franz Benda’s violin sonatas (original line on top, ornaments in the middle):

Or for a little more historical depth, you could always go back to Monteverdi’s “added” ornaments for “Possente spirto” from L’Orfeo:

These pieces are only exceptional because these sets of ornaments have, for various reasons, actually been written out. If a Baroque listener heard us play slow movements “plain,” they’d probably think we forgot to add the salt.

I doubt anybody actually needs any more convincing on this point, but here’s some more just for fun. Additions and substitutions of this kind were common not just in the Baroque, but well into the 20th century. As in, we have recorded evidence for them. I’ll spare you a litany of examples, but one is just too good for me to resist: by far my favorite recording of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto was made by Georg Kulenkampff in 1939.1 Around six minutes in, just before the big theme everybody loves comes back, you’ll hear some stuff in the violin that you’ve probably never heard before. Maybe these additions are part of some older tradition I don’t know about. Or maybe Kulenkampff just made them up. Regardless, they show the flexibility it was still possible to have with respect to concerto scores 200 years after Bach’s death. If, after five decades of recording and the whole Modernist enterprise, it was still possible to be this free with the score, imagine what Early Modern performers must have done. We should try making stuff up more. Just don’t make the cadenza longer than the actual piece.

What I’m Listening To

Beyoncé – COWBOY CARTER

I’m sorry. I know you’re already sick of reading about this album, of seeing more or less the same takes recycled in seemingly every outlet. The last thing I want to do is give you another half-baked thinkpiece about its genesis or significance. Still: the music is (as always) awfully good, and I don’t need to have “something to say” about it here. Some scattered thoughts instead:

– “Beyoncé’s White Album”? I can see it. But surely the better comparison is closer to home: Beyoncé doing an album in the style of her sister. Conceptual apparatus; spoken interludes; songs that function as tesserae more than singles.

– I can’t even listen to the Beyoncé country album without hitting a Jersey club beat?

– “Country album, but like, an album about the country America”? Sure, and I think “Americana” is a better label for the whole album. That puts Beyoncé squarely in line with a whole range of exciting recent musical projects, especially by Black women: Rhiannon Giddens is the most famous, but you’ve also seen me rave about Allison Russell and Brittany Howard. Close harmony, gospel inflections, rock, blues, honky-tonk—it all shows up here and deserves a more comprehensive label than “country.”

— And, well, since Beyoncé interpolates “Good Vibrations” on “YA YA” and opens with an a cappella invocation of sacred styles—I might prefer to call this her Smile rather than her White Album. (Smile is, after all, another of those “albums about America.”)

– Is “FLAMENCO” supposed to be because of the handclaps, or…?

– “Actually, it’s Beyoncé’s rock album.” To me, that’s completely missing the point. At least when it comes to mainstream popularity—not just the charts, but definitely including the charts—country is just about the only form of rock left. There’s rock-inspired pop music: Olivia Rodrigo has made her Spotify artist bio highlight accolades from Rolling Stone and even Pitchfork. And there’s still popular rock—but the Foo Fighters are more “normie” than actually “mainstream.” If you want to hear great guitar-driven rockers in the Top 40, you’re mostly going to get it from country artists like Chris Stapleton. And most of the great licks you hear are going to be on songs by (sigh) Morgan Wallen; he may not do other things well (musically and otherwise), but the riffs are there. Rock may as well be a subgenre of country for the purposes of this album.

— In any case, a lot of the country sounds on this album (e.g. the more fingerpick-y songs) are relatively rare in current country music. It seems designed to show off everything that country is and has been. Including rock.

Empress Of – For Your Consideration

I love this album and have very little to say beyond that. When you listen, you’ll probably roll your eyes at how predictable I am. Yes: still a total sucker for great club beats like “Femenine” and “Cura.” Still eating up sentimental guitar-driven dance ballads like “Baby Boy.” Still jamming to “Lorelei.” A bit disappointed by Rina Sawayama collab “Kiss Me.” Very satisfied with closer “What's Love.” It’s not hard to make an album I love; really, it’s pretty “Fácil.” (Did I mention “Baby Boy”? I really like “Baby Boy.”)

Bruno Cocset and Les Basses Réunies – La Nascita del Violoncello: Napoli – Bologna – Modena

Another one of these? I wonder if Ophélie Gaillard and Co. knew about this project when they were putting together Napoli!

There’s less overlap than you might expect, even on the “Napoli” side. Yeah, there’s Ortiz, Scarlatti, Pergolesi, and Falconieri on both albums. But the pieces here are almost all different, the style of playing is also quite distinct (Cocset is an Anner Bylsma student, and sounds like it), and even the instruments themselves aren’t the same. If you listen closely, you’ll notice that the tunings and sizes of the instruments change with practically every track; Cocset apparently used ten different instruments for this recording. So, as part of tracing the cello’s “birth,” you hear a variety of bass violins (violoncino, viola bastarda, violone, bassetto, etc.). All of those distinctive sounds and colors are the core of the album.

I have to say that the music on the Naples disc is a lot more enjoyable than the Bolognese material (reissued as part of the set). It’s certainly interesting to hear Domenico Gabrielli’s [sic] Ricercars, the first music written for solo cello. But it’s not music that really makes me want to listen further. (The sonatas by Jacchini and Vitali are a little better.) It’s true that they showcase the instruments well, and that matters. Still—a sentence I couldn’t have predicted a week ago—these pieces can’t hold a candle to Disc 1’s pieces by Gregorio Strozzi and Francesco Paolo Supriano (whoever they are). Naples really did have a lot going on musically in these centuries. I guess Ophélie Gaillard had the right idea.

j-hope – HOPE ON THE STREET VOL. 1

KISS OF LIFE – “Midas Touch”

Nobody does a throwback like a K-pop producer. Even at a moment when American culture is supposedly dominated by recycling, when Bruno Mars and Dua Lipa can make their careers out of resurrecting ‘70s and ‘80s dance music, there’s nothing quite like the comprehensiveness and creativity of how K-pop producers revive older styles. There are lots of neo-disco groups in the world (even if “Roly Poly” blows them all out of the water). But good luck finding Motown throwbacks as direct and well-executed as SNSD’s “Lion Heart,”2 neo-doo-wop songs like Secret’s “Shy Boy,” or new New Jack Swing like BTOB’s “WOW.”

All of that goes double for more recent pop styles. For starters, K-pop is OK running a trend into the ground for far longer than American acts can tolerate: acts like ATEEZ were still doing the whole “tropical pop” thing in 2021, a full 6 years after the wave first hit, and at least 3 years after it ebbed away in the US. But it’s also historically been a bit more OK in K-pop to work with styles that sound “dated” but aren’t old enough yet to be “retro.”

In some ways, BTS have exemplified this, with their commitment to thoroughly “90s” hip-hop sounds and trappings. Somewhat insanely for artists that debuted in 2013, they’ve consistently recorded skits, from their first album through to 2020’s BE. (Yes, I think “Skit: Billboard Music Awards Speech” is cringe too.) They even included cyphers on their earlier albums (how I wish they’d kept it up!). And if you listen to those tracks—or a lot else on O!RUL8,2?—you can hear that the beats and rapping can sound strikingly…pre-Kanye? “Paldogangsan” may sound something like a College Dropout track, but songs like “Coffee” and “If I Ruled the World” are as 90s as anything out there. (I confess to the ludicrously hipster belief that this is the most consistent BTS album, and my personal favorite.)

j-hope’s solo music in particular has kept to this stylistic frame. (Just as his namesake J. Cole has remained stuck in older styles.) No skits—leave that to Suga. But there’s still strong throwback energy. The overall sound of an album like Jack In The Box tends to avoid a lot of what’s plagued post-808s rap: minimal use of trap beats, no mumbling, no emo crap (leave that to Suga too), no threadbare instrumentals, no triplet flow, no scotch snaps. (That’s all more or less true of RM’s solo music too, but j-hope doesn’t have the blah R&B tracks either.)

And he keeps it up on this enlistment-era release. If anything, “NEURON” is almost a soundalike of Outkast’s “Ms. Jackson.” That’s not a bad thing per se—what a great song to copy! Really, the only downside is that it draws an implicit comparison, and thus highlights how Hobi is not exactly a Big Boi on the mic. (Yoon Mirae’s verse is pretty great, but we are talking about a very high standard here.)

The rest of the EP is also throwback stuff, but not to ‘90s rap. This is the soundtrack to a “docuseries” about dancing (I haven’t seen it yet), so most of it is explicitly dance-oriented. The core of the album consists of two disco tracks (including a Nile Rodgers feature to hammer it home) and a club track (with a Yunjin feature that just makes me wish for actual LE SSERAFIM beats). J-hope has released dance-oriented music before—and he did get his start as a dancer, as I’m sure the series will emphasize to a nauseating extent—so it’s not exactly a departure. In fact, it’s really more revealing that the relatively undanceable “NEURON” even appears on the album at all. It would seem that j-hope thinks that ‘90s rap is a crucial part of his musical persona, necessitating inclusion even when it’s not 100% on-topic.

I would have left things here at that, but “Midas Touch” was too good an opportunity to pass up. For starters, it’s a great song, probably better than “NEURON” and by far the best thing KISS OF LIFE have put out so far. But it also exemplifies exactly the same musical dynamic. “Midas Touch,” as just about everybody has commented, is the best Britney Spears song in decades: melodic fragments copied from “Toxic” (and even the line “Baby I’m so toxic”), chorus gestures from “Baby One More Time,” instrumentals as “early 2000s” as they could be. (If it weren’t for the more direct Britney references, you could just as easily say that—in a Korean context—this music is a throwback to Lee Hyori or BoA.)

It’s not exactly like it’s “too soon” for American artists to revive “Britney style”: the Olivia Rodrigo-style pop-punk revival is bringing back a trend from the same time. But I haven’t heard anybody try it, and certainly not with results as good as KISS OF LIFE’s. Maybe they will, but I won’t be holding my breath. Whereas: you can more or less count on K-pop producers to bring the recent past back. Now give us BTS Cyphers again.

Also liked…

kinoue64 – The Time Machine School

Eki Shola – Kaeru

Chastity Belt – Live Laugh Love

Daniil Trifonov and Sergei Babayan – Rachmaninoff for Two (yes, really)

Yirinda – Yirinda

Maluf System – Ediwen

What I’m Reading

I thought about writing about Patrick Galbraith and Jason Karlin’s AKB48 when I read it a few months ago, but I decided that it was just a bit too old. Having just reread it and taught from it, I’ve revised my opinion; 2020 is fine, especially when the book in question is this good.

There’s precious little in the way of good scholarship on idol music. For K-pop, there’s basically nothing at all. J-pop at least has Galbraith and Karlin’s 2012 book Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture. All the major topics are in there: the corporate structure of labels, idols and the Japanese TV ecosystem, idol gender presentation and consumption, virtual idols, and more. And the chapters are well-researched and grounded in anthropology, media studies, history, critical theory, and even psychoanalysis.

Remarkably, in their popular-press book about AKB48, Galbraith and Karlin manage to get across a decent amount of the same information. Obviously, some threads had to be abandoned—the gender balance of the 2012 book necessarily disappears, for instance. And there’s no more psychoanalysis, which is honestly a bit of a shame, since Galbraith’s 2012 chapter on desiring the fictions of the idol image is probably the best text available for helping outsiders understand what J-pop fandom even is. But, shockingly, there still is critical theory: a whole chapter is devoted to introducing some basics from Adorno/Horkheimer and others. It’s done with a fairly light touch, and is certainly a good idea for a book that is about a literal culture industry.

There’s not really anything about the music in either book, and that’s probably for the best. Idol pop in Japan tends to be pretty mediocre (although there are definitely good songs, including by AKB48), being heavily constrained by harmonic conventions, extremely flat production, and other clichés. And music is kind of beside the point for most fans. It’s cool that idols make it, but it’s not everything that they are. Still, it would be nice eventually to get some academic writing that tries to understand idol music in J-pop, and why it is how it is.

In any case, Galbraith and Karlin’s AKB48 book is, as far as I know, easily the best introduction available for people wanting to learn about any kind of idol pop. It’s a quick read—just over 100 small pages—and well-written, informative without being too dense. Probably some fans could stand to read it too, but especially for an outsider, it’s a great introduction to a musical world that may seem hopelessly opaque otherwise.

A few others:

NY Times – How Soccer Learned to Embrace Ramadan: From Faked Injuries to Bespoke Diets

Quanta – Overexposure Distorted the Science of Mirror Neurons

LA Review of Books – There Is No Point in My Being Other Than Honest with You: On Toni Morrison’s Rejection Letters

Science –Was Lucy the mother of us all? Fifty years after discovery, famed skeleton has rivals

Architectural Digest – Unpacking the Erasure of Women of Color in Architecture

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

You must be wondering, so I’ll just say that Kulenkampff left Germany in the early 1940s; he’s not exactly a hero, but also not a Hanns Ander-Donath.

It’s not as good of a song, but LABOUM’s “Sugar Sugar” is probably worth mentioning, since it was released a couple months before “Lion Heart” and is also a clear rewrite of “My Girl.”

All the useful words have been genri-fied. Everyone now has a fixed idea of what 'folk' music/'traditional' music/'roots' music/'mountain' music is/should be...Labels are created and enforced because you can't sell something that can't label. Songs of our Native Daughters was a good try at a name. But I'm sure many musicians with native american/first people backgrounds would quarrel with the 'native' descriptor - with some justification. You use the word 'country' today when you want to sell records (that comment has absolutely nothing to do with the quality of the music). And, in B's case, why not? We all know who the buffalo soldiers were. We all know the history of the guitar and banjo.

If a 60's comparandum is required I would suggest Workingman's Dead. But I don't think such comparisons are necessary.

I guess at some point in 30 weeks of concertizing you will inevitably scrape the bottom of the Bachian barrel. Hope you found the iron key with the leather thong!