Week 24: 15 April 2024 – “Allein Gott in der Höh' sei Ehr'”: Easter 3

Plus: Bach and "Variety," ONF say Bye, A New History of the Ancient Near East, and more!

As always, we recognize that Bond Chapel is situated in the traditional homeland and native territory of the Three Fires Confederacy—the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations—as well as other groups including the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Peoria, and Sac and Fox. We remember their forced removal and dispossession, but also remember to speak of these groups in the present tense, as Chicago continues to be resound with tens of thousands of Native voices.

This week, I’ve been (brace yourself) digging into Anishinabe Canadian band Digging Roots. (With two Juno Awards under their belt, they’re not hurting for accolades; I’m just late.) What a fantastic sound! Raven Kanatakta Polson-Lahache can play a mean blues guitar, and both he and his wife ShoShona Kish sing with great urgency and intensity. Seasonally-appropriate track “Spring to Come” highlights both well, and also showcases the wonderful mix of other sounds (including but no limited to indigenous instruments) that they bring to bear: upright bass played like a percussion instrument, a wide range of actual percussion, vocals with inspiration ranging from country to hip-hop. And the lyrical themes are as direct as you could hope for: they sing “I was born here, it's where I belong…This land calls me home again” on “She Calls Me,” a straightforward rocker with a great organ sound and wicked guitar solos. (There are also missteps, like the apparently infamous “Well, I wish I could load / Love into a gun…Well, I load up my AK-47 / And fire, fire, fire at everyone.”) Really just a great band; read more from them here and here.

Week 24: 15 April 2024 – “Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr”: Easter 3

Please save applause for the end of each set

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 715

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 711

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 717

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 675

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 676

Fughetta super Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 677

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 662

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 663

Trio super Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 664

No, it’s not a mistake. It’s not a joke or prank either. And it’s not giving me second thoughts about the “liturgical year” organization either—I knew this would happen, and that’s OK.

Maybe you saw it coming too—congratulations if you’d already figured out that an “Allein Gott recital” was in the offing. If you didn’t, you now know the answer to the “trivia” question I’ve posed a couple times: aside from Christmas and Easter, this is the only week that necessitated an all-chorale program. Like those two recitals, this is one of the longest in the whole series. But of course, unlike them, it’s all based on one tune. What gives? Why this hymn?

Well, “Allein Gott” is awfully important: this is the German version of the Gloria, meaning that it was meant to be sung at most every Mass. Christmas and Easter are important but they don’t come every week. Any special Sunday might deserve a special “Allein Gott” setting. Really, the bigger surprise is that there aren’t more than these nine. (For one thing, Bach never got around to filling out the “Allein Gott” page in the Orgelbüchlein.)

The fact that we end up with three groups of three is a coincidence. (We could just as easily have had ten; in the end, I decided to leave out the controversial and deeply unexciting setting BWV 716.) Still, it does actually point to a real pattern in how Bach organized (and possibly wrote) these pieces. In the case of BWV 662–4, the grouping of three chorales on the same tune matches the preceding trio of three “Nun komm” settings in the “Great Eighteen” manuscript. But BWV 675–7 are anomalies in the Clavierübung III: every other tune is set twice, once with pedals and once without. “Allein Gott” is the only one with three settings.

In a liturgical context, the number three is going to raise some eyebrows. It probably does so too often: following the strong law of small numbers, we should remember that a lot of (or even most) things are going to come in twos and threes, and seeing Trinitarian significance in every triple can lead into conspiracy theory-type territory. Certainly, there’s a long tradition of scholars and amateurs going completely overboard in finding all kinds of numerological significance in Bach’s works (and Mozart’s, and Busnois’); even the most sophisticated of these works, Ruth Tatlow’s Bach’s Numbers, does a decent amount of numerical massaging, erratic counting, and overinterpreting alongside its more solid claims.

But the number of “threes” involved in the Clavierübung III “Allein Gott” settings is awfully suggestive. Not only are there three chorales instead of the usual two; they are also all in three voices (as opposed to the four or more that dominate the rest of the collection). If you want to get cute, you can even note that adding the “extra” chorale made the total number of pieces in the collection equal 3✕3✕3, or 33; given that Clavierübung III’s framing Prelude and Fugue was likely transposed from D or C to E-flat major—three flats—some kind of numerical significance seems in the offing, even if the specifically Trinitarian implications are up for debate. (Does it matter that the “Allein Gott” settings are in a rising sequence of keys that ends up with three sharps?)

Besides, the verses of the “Allein Gott” text do in fact explicitly go through the persons of the Trinity one by one.

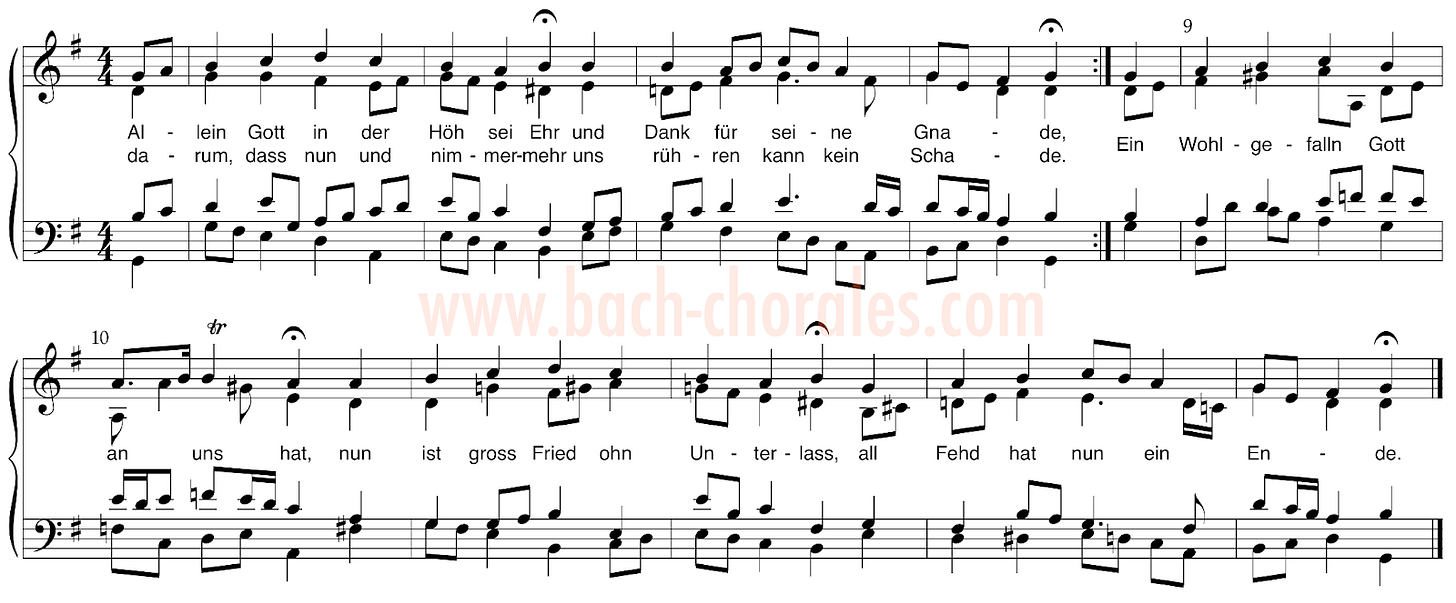

One last “three” to keep in mind before diving into the specific pieces. Here’s the actual tune itself, as set by Bach in BWV 260:

Those first three notes are going to return again and again in this recital. Do-re-mi, the first three notes of a major scale. Funny enough (and Bach surely knew this), they weren’t in the original version, which has a simple one-note upbeat (do-mi):

Still, it’s clear that Bach saw those three notes as a defining feature of the tune. You’ll know them very well by the end of the program.

First a trilogy of early settings. As always, I’m kicking things off with a bang, one of the most extreme examples of Bach having “mingled many strange tones” into a “plain” chorale setting. BWV 715 is loud, full of showy and unpredictable interludes, and harmonized in a vaguely obtuse way. Take the penultimate phrase, which is just an unbroken string of diminished seventh chords:

To me, this almost sounds like the harmonic world of Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, which is to say, a little bit like a horror movie from the 50s.

BWV 711 is a lot tamer but no less interesting. It’s the only surviving Bach chorale in a certain kind of two-part style (some sources label it “Bicinium”): not the slow, decorated style of every chorale partita’s first variation, but a zippy “continuo aria” style with the left hand doing its best cello impression and the right hand just playing the tune in long notes. And even if this piece is less aggressive than BWV 715, it’s still pretty showy (that left hand part!) and has harmonic quirks of its own (that chord at the beginning of the second measure!). For that matter, the same goes for BWV 717 too. Essentially a two-voice jig fugue with the hymn tune floating on top, that piece keeps an equally vivacious pace, and equally can’t resist straying into spicy harmonic territory. I get the feeling that Bach may have been looking for ways to jazz up “Allein Gott.” You kind of have to if you’re playing the same tune every week.

I gave plenty of context about the Clavierübung III “Allein Gott” settings above, so just some quick comments on the actual music. BWV 675 is, like the C3 “Jesus Christus unser Heiland” settings, a really strange piece, full of unusual chords that resolve in unusual ways. With the tune in the alto, it’s almost like Bach is trying to show off the unexpected range of harmonies he can spin around it. And the rhythm is equally irregular, jerking back and forth between sixteenth notes and triplets:

BWV 676 is almost the complete opposite. Harmonically normative and written in an almost continuous stream of sixteenth notes, this chorale sounds for all the world like an Italian chamber piece, albeit one that occasionally pauses one of the parts to play a phrase of the “Allein Gott” tune in longer notes:

As the piece goes on, the pedal joins in on the action, first echoing the tune in canon and then, toward the end, leading the way by giving its own phrase first:

But when they’re not participating in the chorale action, the feet are otherwise bouncing around jauntily. Tough to play, but a delightfully rhythmic result.

The final C3 “Allein Gott,” BWV 677, is the only one of these nine settings to use the original “do-mi” version of the tune, giving it a completely different character. The rhythm and texture is also completely distinct from the previous two C3 chorales, adopting instead something like the Well-Tempered Clavier style of fugue-writing. Still, it’s a nice sibling to the other manualiter setting, BWV 675: the harmonies can get a little crunchy here too, and the lines are (as often in later Bach) strangely contoured, looping back on themselves in unexpected ways. Both are impressively distinct foils for the trio in the middle.

Finally, the trilogy of “Allein Gott” settings from the “Great Eighteen.” Unlike the C3 chorales, these three were probably written separately and only assembled later. So, perhaps inevitably, these three are less obviously complementary—both less of a contrast and less stylistically consistent. And yet, on the sheer strength of the three pieces themselves, they must be one of Bach’s most commonly played chorales “sets.”

The big draw is the first chorale, BWV 662. This piece is famous as one of Bach’s most richly ornamented, sort of like if “O Mensch bewein” went on for another three pages with interludes between the phrases. Just look at all this black ink:

And not just in the tune: unlike “O Mensch bewein,” the other voices are equally fleshed-out, not only ornamented but playing what essentially amounts to a loose double fugue underneath the chorale. It’s all very beautiful, and exceedingly rich: the challenge of this piece is to make all those trills and frills sound organic and not like an overeager encrustation of “more notes.”

BWV 663 can have the same difficulties, which is surprising considering that it starts out sounding like an early draft of the C3 trio BWV 676. Same key, similar figuration, similar texture: given that the trio voices play around with phrases the tune in long notes, it’s a little bit of a surprise when the actual tune shows up in the tenor, in ornamented form. So this one’s actually a quartet, albeit not an equal one. The accompanying parts routinely take breaks to let the tenor spin out a bit of melody, culminating in a full-blown cadenza toward the end:

So in some ways, this piece mediates between two different types of chorale, the heavily ornamented solo of BWV 662 and the trio of BWV 676.

Or, for that matter, of BWV 664, the piece that follows it. Exactly like the C3 trio BWV 676, this trio could almost be a Trio Sonata movement. Actually, this piece imitates violin style even more directly than most of those:

This just is string writing, with string crossings, open strings, and all the rest perfectly accounted for. It also has nothing to do with the “Allein Gott” tune, at least until the last measure of this excerpt (look at the left hand). More than almost any other Bach chorale prelude, this one gives the sense that the hymn tune is just a pretext, that Bach needed some melodic material to play around with and just built his trio out of that. It’s only at the end that the chorale actually shows up, in the pedals. It almost makes me think if it was supposed to be a surprise:

Bach’s Variety Show?

I have to wonder if my old organ teacher, Dr. Van Quinn (may he rest in peace) would have approved of this program. Rightly, I think, he liked to complain about organists who would just slap the “Great Eighteen” chorales on a bulletin and call that a recital program. It’s a good length (for a 90-minute “full recital”) but just too much, not enough variety.

In some ways, that’s a funny complaint to make about a collection like the “Great Eighteen.” As the comments above about the three “Allein Gott” settings hint, this anthology was probably in some ways meant to showcase Bach’s ingenuity—his inventio, his ability to make quite different pieces out of the same tune. You can reach back into your memory for how different the two “Jesus Christus unser Heiland”s and the three “Nun komm”s turned out; and in a few weeks, you’ll hear the staggering contrast between the two “Komm Heiliger Geist”s. If you’re keeping track, that’s fully ten of the Eighteen that form part of a contrasting pair or triple. Not enough variety?

Indeed, over the decades, various scholars and performers have tried to argue that the piece-to-piece contrasts in Bach’s collections—not just the “Great Eighteen,” but the Orgelbüchlein, or even the Well-Tempered Clavier—are purposeful, meant to keep things fresh as you go through the collection. People used to claim that this indicated a potential desire for these collections to be performed as sets; I think most everybody now recognizes that this claim rests on an anachronistic idea of “performance” (e.g. the modern notion of a “concert”) but the underlying sentiment still hangs around. We see these pieces next to each other in the manuscripts and published scores, so we think about how they sound when played consecutively.

Even if that was a concern for Bach and other composers, it’s not necessarily easy to make evaluations like “not enough variety” in a historically appropriate way. To state the obvious, music can vary in a lot of dimensions, and not all of them matter as much as others to different people, let alone different musical cultures and time periods.

The first example I happen to know of an author explicitly writing about musical variety is this famous (in certain circles) passage by 15th-century music theorist Johannes Tinctoris:1

Any really clever composer or improviser [upon a tenor] will bring about this varietas if he composes or improvises now by one mensuration, now by another, now by one kind of cadence, now by another, now by one proportion, now by another, now by one kind of melodic interval, now by another, now with syncopations, now without syncopations, now with fugae, now without fugae, now with rests, now without rests, now melodically embellished, now plain. . . . Therefore every composed work must be diverse in its quantity as well as its quality, as demonstrated by an infinite number of works, not only by me [Yes, he’s very modest], but also by innumerable composers who are flourishing in the present age.

That sounds like a lot of kinds of variety—and it is a lot—but if you parse them out you’ll notice that Tinctoris focuses almost exclusively on rhythmic and textural parameters. There’s probably no conception (and you wouldn’t expect there to be one) of “harmonic” variety, and he doesn’t even suggest using a variety of modes. (Which, to be fair, would be extremely unusual.) And that’s to say nothing of instrumentation, tempo, or any number of other factors that would have been beyond (?) his purview.

Tinctoris also seems to be talking about variety within a piece. (In other passages, he names individual motets as well as large-scale masses as exemplars of varietas.) For all the variety that we can hear in the “Great Eighteen” chorales, they almost all stick to one time signature (the equivalent to Tinctoris’s mensurations), set of rhythmic values (his proportions), and texture; maybe the last verse of “O Lamm Gottes” would have been OK, but I generally get the feeling that he would have preferred the quirky and seemingly random contrasts of the Neumeister Chorales to these “mature masterpieces.” (I imagine he would especially have disliked the almost formulaic repetition of the same musical texture for most of the Orgelbüchlein.)

Really, within a piece, the adult Bach can be almost obsessive about rhythmic uniformity in particular. Think again of the quicker Orgelbüchlein chorales, with their overlapping webs of sixteenth or eighth notes that produce a completely steady pulse at all levels, or of a piece like the “Dorian” Toccata, which just chugs along relentlessly until the finish. For that matter, think of the famous opening preludes of the Cello Suites and Well-Tempered Clavier: not just the same rhythm, but the same figuration for the whole piece. Maybe Bach got this rhythmic preference from Vivaldi, who could be equally willing to write in continuous streams of sixteenth notes. And even to this day (to say nothing about what Tinctoris might have though), some people hate this about Vivaldi (he’s a less risky target than Bach), just like some people hate how Robert Schumann’s music can repeat the same rhythm for two hundred measures at a time.

To go beyond this rhythmic and textural homogeneity: like Tinctoris, Bach and other Baroque composers seem to have been a lot less concerned with harmonic variety than later composers would be. When even slightly later composers like Mozart tried to write neo-Baroque suites, they felt compelled to use a different key for each movement (what Mozart finished of K.399 is in C major, C minor, E-flat major, and G minor); basically no Baroque suite bothers doing this.2 The Goldberg Variations, at 80 minutes or so, only go from G major to G minor for three variations out of thirty; 80 years later, Beethoven felt the need to hint at a different tonic entirely as soon as Variation 13 of the Diabelli Variations. (And by far the longest variation by number of measures—Variation 32—is in the flat mediant.)

*César Franck voice*: “modulez! modulez!”

I don’t think anybody would say the Goldbergs are lacking for variety, though. Nor would they say that about Bach’s sets of suites. A lot has been made of the ways in which Bach seems to have purposefully differentiated these pieces from each other: how all of his published suites are in different keys (with different tonics); how the Six Partitas each use a different kind of opening movement and a different time signature for their closing jigs; how the Goldbergs include canons at every interval from the unison to the ninth, and themselves use every vaguely common time signature, from 4/4 to 18/16. Just like how the three C3 “Allein Gott” settings each exhibit a different type of three-voice texture.

So there is a sense in which Bach’s collections (especially those “written to order” and/or published) were designed for contrast and variety. But that still leaves a question of why. “Listenability” as a set is a possibility but hardly the only one. Considering that some of these sets—the Orgelbüchlein and “Great Eighteen” especially—are almost impossible to imagine being used as anything other than anthologies, and were potentially not even intended for circulation,3 we have to imagine other reasons to aim for this kind of diversity.

The reason you come up with will probably depend on how you conceive of Bach’s personality. For instance, a relatively familiar explanation is Bach’s purported desire to be “encyclopedic” or “systematic”; it’s probably not a coincidence that German musicologists like Christoph Wolff gravitate toward this line of thought. Performers and music critics seem more likely to go with the “listenability” explanation. And oddly underexplored (what does that say?) is the idea of these collections as some kind of cabinet of curiosities; to put a religious spin on the same idea, they could be showcases for the diversity of (musical) Creation.

For that matter, they might also just reflect Bach’s simple desire to try something new, to avoid repeating himself too much. Some of these “Allein Gott” settings end up working with very similar musical ideas, but even then Bach does quite different things with them. BWV 715, 711, and 717 weren’t written or collected together, but they’re even more diverse than the C3 settings.

As usual, it’s probably more than one thing. Maybe even all of these explanations are true at the same time; they hardly exclude one another.

And we don’t really have to care which explanation is right when programming recitals; maybe we even shouldn’t, since the primary objective tends to be (I hope!) to make the concert work for a present-day audience. It doesn’t even really matter what sets might have sounded sufficiently varied in Bach’s day; if it would bore you and me, then it’s probably best to come up with an alternative anyway.

Which is all a longwinded way of saying—I do think these nine “Allein Gott” settings have enough variety to work as a half-hour recital. They don’t have the biggest drawback of the “Great Eighteen,” that deadly succession of three long sarabandes in a row near the beginning; “Komm Heiliger Geist” No. 2, “An Wasserflüssen Babylon,” and “Schmücke dich” are great by themselves but when they’re played consecutively you end up with well over 20 minutes of the same slow tempi and lilting 3/4 rhythms. By contrast, the most similar entries on today’s recital—the two trios and the “quartet” BWV 663—are vivacious and engaging. Even if they get a little samey (which I doubt), they’re not going to lull anybody to sleep. I hope.

What I’m Listening To

Maria Mazzotta – Onde

Kiran Ahluwalia – Comfort Food

I have to be careful, because I suspect that some of the things I like about Onde—and I really like it—probably annoy those who are closer to its musical sources. As best I can tell, Mazzotta’s current style is a combination of southern Italian folk styles (most obvious to me on middle tracks “Damme la manu” and “Navigar non posso”), post-rock (“La furtuna”), desert blues (Tuareg guitarist Bombino appears on “Sula nu puei stare”), and flamenco vocal styles. That’s a lot to cram in, and I can imagine that more acculturated listeners might hear, for instance, an element of racial pantomime in her singing, à la Amy Winehouse or (closer to home) ROSALÍA.

Fair enough if so. I also happen to really like ROSALÍA and Amy Winehouse. Not as “authentic” expressions of anything in particular, but for what they do with the musical traditions they ransack. And Mazzotta is in some ways more creative than either. I’ve heard a lot of flamenco pop (and I tend to like it somewhat indiscriminately), but flamenco blues and flamenco rock are much fresher for me, and both combos work brilliantly here. The rasp in Mazzotta’s voice and the fuzz on Ernesto Nobili’s guitars bring a real edge to songs like “Terra ca nun senti,” make passionate laments out of songs like “Canto e sogno,” and just plain rock out on “Viestesana.” It may give some people the “world music icks,” but I find Onde pretty irresistible.

I originally was going to discuss Comfort Food separately, not least because I like it even more than Onde and wanted to highlight each independently. But it increasingly felt like a deeply silly exercise not to bring these albums into conversation with each other. Onde and Comfort Food share a surprising amount of musical DNA. Expect to hear desert blues (“Dil” especially) and flamenco (“Ban Koulchi Redux”) elements here too.

The differences are probably just as clear as the similarities. There’s the obvious fact that Ahluwalia’s musicality is rooted in ghazals and Mazzotta’s in Apulian folksong. And springing from that difference, Ahluwalia has somewhat of a greater distance to bridge than Mazzotta does when it comes to (for instance) integrating flamenco sounds. (I don’t want to overstate this distance: goodness knows that fusion-minded Hindustani musicians from Anoushka Shankar to Anandi Bhattacharya have explored this territory before.)

Or rather, Ahluwalia doesn’t necessarily work to bridge the gap: she’s willing to let styles and sounds coexist, like the rock guitars/organ and tablas on “Jaane Jahan.” I think people would probably call both of these “fusion” albums of some kind, but Mazzotta’s is significantly more “fused,” while Ahluwalia’s is a lot more heterogeneous. I like both approaches.

Bagus Shidqi – Digital Indigenous 06: Njondhal Njondhil

Funny enough, I originally had planned to pair Comfort Food with this album. Now that I think about it, I can’t really find any logic behind that. I wonder if I was subconsciously recalling an earlier pairing—Bhattacharya’s album (it’s not that similar to Ahluwalia’s, but I do really like it) came out around the same time as Susheela Raman’s fabulous Ghost Gamelan, and maybe I just wanted Bagus Shidqi to fill that role.

I have literally no idea if this album is any good or not, because it would basically be impossible for me not to like it. I will listen to any pop-gamelan hybrid you put in front of me, and I’ve happily waded through hours and hours of Didi Kempot greatest hits for traces of gamelan instruments. In this case, the electronic instrumentation makes for a result that sounds oddly chiptune-esque, like gamelan videogame music with slightly wry vocals floated into the mix. It’s kinda crazy. Of course I love it.

Tine Thing Helseth and tenThing – She Composes Like a Man

Do I think this is a great album? Honestly, I’m not sure, but it’s so off the wall that I feel compelled to plug it anyway. Helseth’s…thing (I’m so sorry) has long been brass band arrangements of pops hits and trumpet versions of vocal music both famous and obscure; even knowing that she’s Norwegian (and that there will therefore be Grieg) isn’t quite sufficient preparation for the selection of lesser-known lieder she chose for her debut recital record.

This album is something else entirely. I’m not sure I ever wanted or needed to hear a chipper brass band arrangement of two of Lili Boulanger’s Trois Morceaux, or of choral works by Clara Schumann, or of Fanny Hensel’s “Schwanenlied.” It’s a very confusing experience, giving neither the sense that these were obvious choices for brass, nor that the pieces are much illuminated by the act of arrangement.

On the other hand, the players and ensemble are top-notch, and they do sound like they’re having a great time. And the one organ piece on the album (Florence Price’s now-ubiquitous “Adoration”) really does work. I’m bewildered, but I’m glad I gave this record a chance, and I hope you do too.

ONF – Beautiful Shadow

ONF (if you don’t know, try to guess how their name is pronounced before you look it up) have a discography full of really great songs that don’t quite land with me. A song like “Complete” has absolutely everything going for it:

Lots of huge tunes, a great beat, big vocals, fantastic pacing, creative and constantly-changing instrumental choices, and a breakdown that really ups the ante without killing the song’s momentum. MonoTree (producers for most all of ONF’s discography) don’t mess around at all: there’s no dull moment, no cringe rap break, no bizarre melodic changeup after the first chorus. And “Complete” is far from their only great song; “Beautiful Beautiful” does all the same things right and avoids basically all of the same mistakes:

To me, this song sort of answers questions like “What would it take for a One Direction song to actually be good?” (Answer: a whole lot, but it’s not actually inconceivable.) The synth sounds alone make for a great listen, and the bridge is just fantastic, gesturing dangerously toward a cheesy modulation but instead taking us back to an a capella chorus that actually works for once.

And yet…I dunno. These songs, and ONF’s other great singles, and their excellent B-sides, mostly just don’t quite stick for me.4 The tunes never quite manage to stay in my ear, the harmonies never quite pull me along, and the songs tend to fall out of my rotation.

Maybe that’ll change now; I think “Bye My Monster” will stick around. I’m not even sure it’s as perfectly executed of a pop song as “Complete,” but it’s close enough, and this song’s construction pushes all the right buttons for me. Among non-ballad K-pop songs, this has one of the best builds I’ve heard.

Start with the first verse, built on music hall-esque piano over a gentle trap beat. (Yes, I know that those three words should never go together but this is where we are as a society.) Strings enter with Wyatt, only to cut out (alongside the programmed beats) when Seungjun and a set of rhythmically active female backing vocals come in. All the while, the dynamic level has remained subdued (actually getting quieter in the brief prechorus)—but the pitch level keeps rising, even as the backing and rhythmic density gets cut back under the vocal line. You know something big is coming.

It is. It’s nice to hear a chorus where a pretty decent singer (Hyojin, followed by Seungjun the second time) really gets to shine in close harmony; it reminds me of INFINITE in ways that even INFINITE V’s excellent recent song doesn’t. And MonoTree manage to underpin that chorus with truly massive-sounding guitar and drum parts that somehow don’t crowd the vocals out of the mix. Maybe you think the string break that follows is a bit cheesy, but it works well as a natural outgrowth of the chorus.

For me the real fun starts in the second verse, when the original piano part and strings mutate into a tango-esque tresillo 3+3+2 rhythm; after over a minute of rhythmically driving but only lightly syncopated music, the intrusion of this rhythm has a striking and propulsive effect. And somehow, the “tropical” trap break that follows doesn’t completely kill the song en route to the second chorus; I can’t think of many other producers who could pull that off. The remaining choruses close out the song nicely.

Honestly, I could probably dissect a lot of ONF’s songs in this way and have them come up looking similarly creative. (Writing out analyses of K-pop is especially dangerous, since a huge number of singles—especially pre-NewJeans—are stuffed full of describable musical details that don’t necessarily have a huge relationship to the overall quality or effect of the song.) What I don’t think I’ve adequately been able to describe is the song’s arc, its sense of growth. Songs like “Complete” and “Beautiful Beautiful” are great because they don’t grow much, because they start out close to an 11/10 and don’t let up. Even previous “darker” ONF songs like “Goosebumps” begin at a higher intensity, putting the quieter sections pre-chorus. So this is a real departure for them, and fairly unusual for songs in this style in general.

I have to admit a soft spot for songs with a big arc. ONF aren’t trying to be Arcade Fire (make fun of the lyrics all you want, but that is a great build), and this isn’t a power ballad à la IU (sorry, I mean “Liebesgedicht”), but within the constraints of an uptempo lead single, they’ve managed to deliver something that scratches some of the same itches. The B-sides (especially “Aphrodite” and “Slave to the Rhythm”) are great too. This has to be my favorite ONF album; it’s nice for once to feel that it’s great stuff and not just think it.

Also liked…

Jane Weaver – Love in Constant Spectacle

Quatuor Danel – Dmitri Shostakovich: The Complete String Quartets

Vampire Weekend – Only God Was Above Us

Cacha Mundinho – Vento do Mar

Arsène Bedois and Ensemble vocal Guillaume Dufay – Messes Polyphoniques de l’Ars Nova: Le Manuscript d’Apt (extraits) et l’École de Florence

Khruangbin – A LA SALA

What I’m Reading

I picked up Amanda Podany’s Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East on a whim and I’m glad I did. I’d never gotten around to reading any other history of Ancient Mesopotamia, so I couldn’t tell you how “new” this one actually is. (Marc Van De Mieroop does claim to be impressed on the jacket blurb, and he would know.) But it’s entertaining, informative, and at least seemingly reliable.

Podany’s title actually says quite a lot about how the book is organized. It’s a little bit in the “slice of life” style, giving hundreds of individuals a couple of pages each, based mostly on surviving cuneiform documents. And the order is intentional: Podany gives manual laborers and other “civilians” pride of place. Women are centered throughout (with convincing arguments that this is more “natural” for Sumer and the early 2nd millennium BC in particular). This is not just a standard political history.

It also, to be fair, includes basically every beat of the standard history that you’d expect—there’s plenty about those “Kings,” especially after around 1500BC. All of the big names get their due, albeit often with caveats explaining that their importance has been exaggerated (Hammurabi) or assigned to the wrong things (Ur-Nammu’s law code). Historiographical commonplaces that are now in doubt (like the role of the Gutians and Sea Peoples in various historical transitions) still get trotted out, if only to be debunked. Political history still forms the narrative backbone of the book, and despite its “newness,” nobody will feel cheated that they didn’t learn about Tiglath-Pileser III or whoever.

Otherwise, Podany does make an earnest effort to try to cover just about every important topic: sculptural practice, mythology and poetry, foodways (there’s a tasty-sounding stew recipe in the book), astronomy, and most anything else you can name gets at least a cursory treatment. With some subjects it’s very cursory indeed—she doesn’t seem all that interested or happy to talk further about Babylonian mathematics. Others get very extensive treatment: Podany’s published a decent amount about Ancient international relations, and that comes across quite clearly (the Amarna-centric chapters are great). I was happy to find that music and language are two of her favored subjects. So, I learned a lot about both the role of music in Ancient Mesopotamian life and the secondary literature on it—and got lots of lovely and suggestive tidbits about, e.g., documents that use Akkadian case endings for Egyptian words.

There’s a limit to how technical any of that discussion gets (another possible reason the math gets short shrift): this book is clearly designed to reach as wide a readership as possible, and Podany even implicitly suggest that she’s trying to write an updated version of the kind of general-public history books about Ancient West Asia that Mortimer Wheeler and others put out in the first half of the twentieth century. So, she begins with a discussion of the Ea-Nasir meme; the style is very informal (easy to read although occasionally not edited very well for repetitions); there are a decent number of illustrations; and the terminology is all explained carefully. (I found some of the historiographic clarifications helpful—always wondered why it’s the “Third Dynasty of Ur,” and now I know.)

Every “general readership” history has an angle of some kind, and Podany’s is no different. I strongly suspect that some of this book’s emphases are a reaction to anarchist anthropologists like Jim Scott, who have proposed that early “civilization” was miserable and coercive. Podany argues basically the exact opposite. She repeatedly insists that everyday life was for the most part reasonably peaceful, that family bonds were strong and important, that people back then were basically like us. (Maybe that’s why music plays such a big role?) At some points that insistence begins to feel like a premise rather than a conclusion.

But I don’t want to make it sound like Podany is distorting her evidence. On the one hand, she necessarily is, by the act of selecting and translating her sources; but she’s consistently quite careful with her “mights” and “it seems,” and with providing alternate theories that contradict her own. Even if she clearly favors a certain picture, she doesn’t let it monopolize her narrative.

So, while I don’t know enough to really evaluate how accurate, comprehensive, or up-to-date this book is (from what I can glean, other scholars in her field seem to like it), but it’s certainly an enjoyable read, and choc-full of interesting threads to pursue. I can’t ask for much more from an introductory history.

A few others:

Bits About Money – Anatomy of a credit card rewards program

Sixth Tone – Chinese Surnames Are Changing. Why?

IMF.org (Angus Deaton) – Rethinking Economics or Rethinking My Economics

Artforum (J. Hoberman) – Vulgar Minimalism: Bill Griffith’s Three Rocks and the cult of Nancy

Nature – A global timekeeping problem postponed by global warming

Thanks for reading, and for listening if you can make it on Monday!

The translation is from Emily Zazulia, who in turn is modifying a translation by Jeffrey Dean.

I first got this example from something by Charles Rosen; forgive me for not remembering which book.

In the case of the “Great Eighteen,” we don’t even really know how much of the collection was Bach’s plan—it was copied in stages, and not all by Bach.

I’ll completely ruin my reputation (what’s left of it?) and say that my favorite song before this week was probably the utterly silly “introductions” song “My Name Is.” That’s also a way to find out how ONF is pronounced, for what it’s worth.

Interesting to consider Petrarch from the point of view of variety. His Rime are famous for internal contrasts but the poems seem 'samey' when compared to Shakespeare's Sonnets. His letters feel like exercises when compared to Cicero's or Pliny Jr or Seneca Jr. From this distance it appears that he is developing tools but doesn't have any 'killer' applications (the Africa poem for instance).

With Bach there is a range from clear 'exercises' to 'killer applications,' even within one 'grouping.' SInce the whole set of issues around performance, publication etc...make it hard to compare Bach's 'books' to anything we know, talking about structure in a single grouping can be hard. Goldberg's are the outstanding exception.

The Ancient 'Middle East' is getting a long awaited makeover ('Late Antiquity' has already received this treatment)...I hope it disappears into Ancient Eurasia very soon.